eBook - ePub

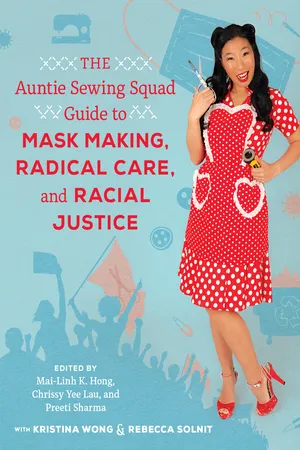

The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice

About this book

The rise of the Auntie Sewing Squad, a massive mutual-aid network of volunteers who provided free masks in the wake of US government failures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March 2020, when the US government failed to provide personal protective gear during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Auntie Sewing Squad emerged. Founded by performance artist Kristina Wong, the mutual-aid group sewed face masks with a bold social justice mission: to protect the most vulnerable and most neglected.

Written and edited by Aunties themselves, The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice tells a powerful story. As the pandemic unfolded, hate crimes against Asian Americans spiked. In this climate of fear and despair, a team of mostly Asian American women using the familial label "Auntie" formed online, gathered momentum, and sewed masks at home by the thousands. The Aunties nimbly made and funneled masks to asylum seekers, Indigenous communities, incarcerated people, farmworkers, and others disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. When anti-lockdown agitators descended on state capitals—and, eventually, the US Capitol—the Aunties dug in. And as the nation erupted in rebellion over police violence against Black people, the Aunties supported and supplied Black Lives Matter protesters and organizations serving Black communities. Providing hundreds of thousands of homemade masks met an urgent public health need and expressed solidarity, care, and political action in a moment of social upheaval.

The Auntie Sewing Squad is a quirky, fast-moving, and adaptive mutual-aid group that showed up to meet a critical need. Led primarily by women of color, the group includes some who learned to sew from mothers and grandmothers working for sweatshops or as a survival skill passed down by refugee relatives. The Auntie Sewing Squad speaks back to the history of exploited immigrant labor as it enacts an intersectional commitment to public health for all. This collection of essays and ephemera is a community document of the labor and care of the Auntie Sewing Squad.

In March 2020, when the US government failed to provide personal protective gear during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Auntie Sewing Squad emerged. Founded by performance artist Kristina Wong, the mutual-aid group sewed face masks with a bold social justice mission: to protect the most vulnerable and most neglected.

Written and edited by Aunties themselves, The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice tells a powerful story. As the pandemic unfolded, hate crimes against Asian Americans spiked. In this climate of fear and despair, a team of mostly Asian American women using the familial label "Auntie" formed online, gathered momentum, and sewed masks at home by the thousands. The Aunties nimbly made and funneled masks to asylum seekers, Indigenous communities, incarcerated people, farmworkers, and others disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. When anti-lockdown agitators descended on state capitals—and, eventually, the US Capitol—the Aunties dug in. And as the nation erupted in rebellion over police violence against Black people, the Aunties supported and supplied Black Lives Matter protesters and organizations serving Black communities. Providing hundreds of thousands of homemade masks met an urgent public health need and expressed solidarity, care, and political action in a moment of social upheaval.

The Auntie Sewing Squad is a quirky, fast-moving, and adaptive mutual-aid group that showed up to meet a critical need. Led primarily by women of color, the group includes some who learned to sew from mothers and grandmothers working for sweatshops or as a survival skill passed down by refugee relatives. The Auntie Sewing Squad speaks back to the history of exploited immigrant labor as it enacts an intersectional commitment to public health for all. This collection of essays and ephemera is a community document of the labor and care of the Auntie Sewing Squad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice by Mai-Linh K. Hong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Sewing with Intent

CHRISSY YEE LAU

Five days after police suffocated George Floyd on the streets of Minneapolis in broad daylight, Auntie Sewing Squad Headquarters (HQ) declared that May 30, 2020, was the Auntie Sewing Squad Day of Solidarity with the Black community and the Black Lives Matter movement. Although the group was founded by Asian American and Pacific Islander women, it grew to include Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC). HQ recognized the urgency for non-Black members to stand in solidarity with the Black community and support the Black Aunties in the Squad. HQ asked non-Black Aunties to “sew with intent” for Black communities affected by state-sponsored violence, or to participate in antiracist work, and reminded Aunties the communities for whom they were sewing have long been harmed by structural violence and racism. Aunties shared readings, videos, and podcasts about ways to support Black communities. And HQ reminded Aunties that if they decided to participate in protests, they must wear masks.

The Squad’s call for “sewing with intent” was a continuation of the effort to build solidarity between Asian Americans and other BIPOC communities. Since the 1960s, Asian Americans have been mythologized in popular US culture as the “model minority”—law-abiding, self-sufficient, and not Black—in order to erode the civil rights demands of Black activists and absolve the US government from responsibility for addressing institutional racism against African Americans.1 Some Asian American leaders, after years of exclusion laws, segregation, and incarceration, endorsed this portrayal in order to acquire resources long denied them. Still, in 1968, a new generation of Asian American student activists rejected the model-minority stereotype and provided a different model. At San Francisco State University, they stood for six months alongside Black, Latinx, and Indigenous students as part of the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) to demand a redefinition of education. They called on the administration to establish a school of ethnic studies and an admissions process that equitably enrolled more students of color. The Auntie Sewing Squad inherits its understanding of solidarity from the TWLF student strike and is a beneficiary of the establishment of ethnic studies.

The Auntie Sewing Squad also draws lessons from women writers of color who offered critiques of the feminist movement in the 1970s and 1980s. To “sew with intent” builds on what the Black writer and feminist bell hooks once called doing “the dirty work” of solidarity: embracing the struggle and confrontation necessary to build political awareness.2 When women of color criticized white feminists for unaddressed racism, white feminists responded by excusing racist policies or actions because they were well-meaning. For non-Black members of the Auntie Sewing Squad, sewing with intent meant examining their own complicity and their positioning in a racially stratified society that devalued Black lives. By understanding how the disenfranchisement of BIPOC communities in the United States led to the disproportionate negative impact of COVID-19 on those communities, Aunties could resituate pandemic mask making—what some other sewing circles considered an act of charity—as an expression of solidarity. By doing the “dirty work” of addressing racism, the Auntie Sewing Squad acknowledges its debt to earlier social movements and writers and centers solidarity as its basis for Asian American feminist mutual aid.

The Squad’s approach to mask making reminds us that solidarity is an ethic passed down from generations of BIPOC critique and organizing. The Super Aunties of the Squad redirected their professional research and outreach skills to establish contacts in vulnerable communities and get masks to the places where they were most needed. Sewing and Caring Aunties, like me, joined the Squad and embraced our sewing skills because we had also made a commitment to serve BIPOC communities through our own education, or developed a commitment as a result of participation in the Auntie Sewing Squad.

This essay combines oral histories, archival sources, and personal reflection to record the solidarity praxis of the Auntie Sewing Squad. Solidarity is hard work. Solidarity demands that organizers carefully listen to and coordinate with those most vulnerable. Solidarity leads to intentional collaboration with community-led organizations already doing the work on the ground. Solidarity requires people and institutions to commit to self-education, reflection, and political reckoning. It reframes mutual aid as “solidarity, not charity”: a distribution of resources in recognition of systematic injustice. Along the way, the Auntie Sewing Squad did its best to show up for all BIPOC communities.

LISTENING TO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

In mid-April 2020, members of the Auntie Sewing Squad had been sewing masks mostly for healthcare workers in nearby hospitals, friends, and family members, but they shifted focus in order to meet the needs of the BIPOC communities hit hardest by COVID-19. Indigenous communities were especially badly affected because the federal government withheld congressionally allocated relief for several months. Congress had set aside $8 billion for tribes when it passed the CARES Act in late March. By late May, Indigenous communities had received only about half this amount. In mid-June, a federal judge had to force the Treasury to disburse the final half of the federal relief to the tribal lands.

The delay in pandemic relief was part of a long history of obfuscation and incompetence by the Treasury in working with tribes. Both the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service were created as a result of treaties between Indigenous populations and the US government, by which tribes gave up land in exchange for the promise of social services, including housing, education, and healthcare. Indigenous communities are the only people in the United States with the legal right to health services.3 However, such services have been chronically underfunded. The most recent delays in providing relief caused irreparable damage. By May, the Navajo Nation had more confirmed COVID-19 cases per capita than any state, with over three thousand cases and at least one hundred deaths. The spread of COVID-19 particularly affected women, who were the main caregivers for the sick. For instance, Valentina Blackhorse, a twenty-eight-year-old mother who dreamed of leading her people as the future president of the Navajo Nation, died while caring for her boyfriend, who had COVID-19.

Cognizant of this history, the Auntie Sewing Squad worked with Indigenous organizers at the grassroots level. Constance Parng, the Super Auntie in charge of Indigenous mask campaigns, partnered with the Bear Soldier COVID-19 response team, formed by members of a volunteer fire department on the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) to Indigenous communities. Although not a mask maker herself, Parng had years of experience working in nonprofit organizations. At a time when PPE was severely limited, she was able to secure donations of hand sanitizer as well as 3D-printed masks. While Parng gathered supplies, the Bear Soldier team made plans to distribute food and masks to Indigenous communities.

Parng’s grassroots approach had begun years earlier, when she participated in the Teach for America program on Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. She saw firsthand how badly reservations were underresourced. The protests against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in 2016 were another turning point for Parng. Activists at the Standing Rock Reservation protested the construction of the oil pipeline that threatened to contaminate their water supply. They also argued that the pipeline, funded by private developers, risked destroying Indigenous cultural landmarks and ignored consultation on its environmental impact. As Parng put it, “It was difficult to witness the blatant disregard for Indigenous rights, treaties, and the environment.”4 Asian American writers and activists called for solidarity with the #NoDAPL movement through petitions, divesting from private companies that funded the pipeline, and sending much-needed supplies to Standing Rock.

Parng’s experience with #NoDAPL shaped the Auntie Sewing Squad’s mutual-aid efforts. Because the threat of COVID-19 exacerbated the serious shortage of medical care and supplies on Native lands, Parng led the first coordinated mask drive with the Auntie Sewing Squad for Indigenous COVID-19 patients. She identified the gaps between charitable donations and hospital policies. Like many other hospitals, the Gallup Indian Medical Center in New Mexico lacked the capacity to care for the influx of new patients, who instead stayed at nearby motels. Donors and sewing groups sent some PPE directly to the Gallup Indian Medical Center, but the medical center’s policies did not allow the PPE to leave the hospital. The Auntie Sewing Squad was able to send 189 cloth masks with minimal efficiency reporting value (MERV)-rated filters, as well as five hundred surgical masks, to the patients in motels.

In mid-May, Parng launched a campaign to source and send five thousand masks to a network of Indigenous COVID-19 testing sites. The campaign rallied at least fifty members, including me, to pledge to make masks. Until then, I had hand-sewn masks from fabric scraps for friends and colleagues. I had joined the Auntie Sewing Squad to find camaraderie with a collective of mask makers when the prevailing official attitude was that wearing a mask was not proved to be effective. I wrestled with the question of purchasing a sewing machine, restrained by my immigrant, working-class frugality and many years of living on a graduate student budget or holding precarious short-term lecturer positions. My indecision led to missed opportunities, since sewing machines were selling out online. But when Parng posted the call for masks for Indigenous communities, and my now-steady income as a tenure-track...

Table of contents

- Imprint

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface, Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord

- Taxonomy of Auntie Roles, Audrey Chan

- Introduction

- Labor

- Solidarity

- A Day in Our Virtual Life

- Survival

- Mutual Aid

- Posterity

- Coda, Mai-Linh K. Hong, Chrissy Yee Lau, and Preeti Sharma

- Timeline

- Auntie Sewing Squad Mask Sewing Patterns, Mai-Linh K. Hong and Chey Townsend

- Contributors

- Index