- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ingredients for Great Teaching

About this book

Teaching would be easy if there were clear recipes you could follow every time. The Ingredients for Great Teaching explains why this is impossible and why a one-size-fits-all approach doesn't work.

Instead of recipes, this book examines the basic ingredients of teaching and learning so you can use them wisely in your own classroom in order to become a better and more effective teacher.

Taking an approach that is both evidence-based and practical, author Pedro de Bruyckere explores ten crucial aspects of teaching, the research behind them and why they work like they do, combined with everyday classroom examples describing both good and bad practice.

Key topics include:

This is essential reading for teachers everywhere.

Instead of recipes, this book examines the basic ingredients of teaching and learning so you can use them wisely in your own classroom in order to become a better and more effective teacher.

Taking an approach that is both evidence-based and practical, author Pedro de Bruyckere explores ten crucial aspects of teaching, the research behind them and why they work like they do, combined with everyday classroom examples describing both good and bad practice.

Key topics include:

- Teacher subject knowledge

- Evaluation and feedback

- The importance of practice

- Metacognition

- Making students think

This is essential reading for teachers everywhere.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ingredients for Great Teaching by Pedro De Bruyckere,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Cooking, Medicine and Evidence

This chapter will explore the following questions:

- Why is it impossible to have clear recipes in education?

- What do average effect sizes in educational research hide?

- What is the difference between evidence-based and evidence-informed education?

The moral of the burnt steak…

What is the secret of a masterchef? Of course, he or she probably has access to the very best ingredients, but even a simple egg fried by a star-rated chef is better than what an average family gets on their breakfast plates each morning. On the other hand, using the best ingredients is not, by itself, a guarantee of success. Here I am speaking from bitter personal experience, since I once rendered a delicious (and very expensive) piece of Wagyu steak wholly inedible!

Too much salt, not enough pepper, too sour, too sweet: all of these things are possible, in addition to too raw and (in my case) too burnt. The difference between a masterchef and a master bungler is the difference in the extent to which a person possesses the necessary techniques that allow them to make best possible use of the ingredients at their disposal.

It is exactly the same in education. John Hattie1 has repeatedly told us that almost everything in education has a positive effect, but that some things are more positive than others. The truth, however, is more complex than that. For example, reference is often made to the positive effect of feedback. But this does not mean that all forms of feedback result in better learning. Worse still, some types of feedback can actually have a negative impact. In much the same way, direct instruction and self-discovery learning have both acquired negative connotations in recent years, albeit from different groups in different places, and it has to be admitted that both are open to question. But should they both be consigned to the dustbin of educational history? No, that is not a good idea. Naturally, we also need to remember that some things, such as learning styles, have very little or no effect, but I have already written a book about that.2

Why masterchefs have it easier than teachers

In one sense, Gordon Ramsey, Heston Blumenthal and all the other world-famous chefs have it much easier than teachers. They have the luxury of just choosing a single recipe to make a perfect dish. Even then, things can sometimes go wrong, but don’t underestimate the importance of having a single step-by-step plan. In most cases, it works, and works well. In this context, the difference between education and cooking is huge. No matter how much teachers (and policy-makers) would like it to be true, in education there is no such thing as a recipe that works in all circumstances. Policy mandarins might continue to dream of applying the Finnish recipe to our educational system, but a simple copy-and-paste of Finnish methods offers no guarantee that those methods will work with equal success when superimposed on a different country or region. This is frustrating, yet also a cause for optimism.

Further thinking: Why the education pyramid cannot be right

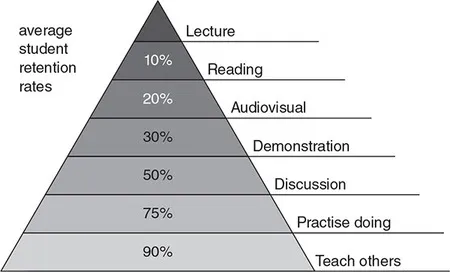

In our earlier book about educational myths, we talked about the Loch Ness monster of educational theory: the learning pyramid (see Figure 1.1). I do not intend to repeat the whole story here. But because it is relevant to what follows here, I would at least wish to re-emphasize the following conclusion: if the pyramid is right, then there really is a single method of teaching that works best in every context, for every purpose and with every pupil. But is that what we actually believe?

Figure 1.1 The learning pyramid

Source: National Training Laboratories, Bethel, Maine

Frustration

The lack of a one-stop recipe in education is frustrating because it means that there are seldom simple solutions to important educational challenges. When we were writing our book Urban myths about learning and education, we soon discovered that this desire for simple solutions was frequently an important part of the appeal of such myths. They offer, or seem to offer, quick and easy answers. In his book When can you trust the experts?, Daniel Willingham3 warns us that these solutions are often mistakenly applied to different problems at the same time: do this, the theory says, because it works for dyslexia, ADHD, truancy and even sweaty feet! Okay, I admit that even teachers wouldn’t try it on the last one. But there are some who would try it on just about everything else. What’s more, simple solutions become even more attractive when teachers are under pressure. And in many cases, the teacher’s job already involves above-average levels of stress. Educational policy-makers are also charmed by simple solutions, to some extent because they are uncertain about the quality (and qualities) of their own teaching staff. More than once in recent years we have seen the introduction of methods and materials that are supposedly ‘teacher-proof’. In other words, methods and materials that even the biggest idiot in the world could use to obtain excellent results with any child. (Of course, I exaggerate; but not by much.) Nowadays, there are even plans to introduce bots and robots in the classroom. By this, I don’t mean the jazzy multi-coloured machines that help motivate pupils to develop their programming skills, but rather a series of smart applications that are intended to guide pupils through their learning process. This is no longer science fiction but science fact, and it is a dream that appeals to many. As long ago as 2011, Watson, the supercomputer developed by IBM, was able to beat the strongest candidate on the American TV quiz show Jeopardy. Since then, Watson has already been used to support doctors in their work4 and the idea is to now do the same for teachers.5 But IBM and Pearson, who are currently trying to sell Watson to the educational world, use a crucial word in their promotional blurb: support. Fortunately, the discussion is not about (or at least is no longer about) replacing teachers in the classroom, because even in our high-tech age of supercomputers and mega-apps people have finally come to realize that human interaction will always be a crucial part of the educational process.

Further thinking: Jill Watson

Like most teachers, the number of emails I get from my students is in inverse proportion to the amount of time that remains before they need to hand in their next paper or before their next exams. Email is a fantastic invention, but one that seems to be costing us more and more of that precious commodity: time.

Imagine for a moment that you could use a robot to answer some of these mails. Many of the answers involve a standard text, because students tend to forget the same things or are too lazy to look them up. Often, it’s just quicker and easier (for them) to ask the teacher. Professor Ashok Goel of the Georgia Institute of Technology suspects that in the near future it will be possible for everyone to answer 40% of such emails in this way. In fact, he knows it for certain, because he has already used this kind of smart technology with success. In recent months, his students have regularly received replies from his assistant, Miss Jill Watson, who answers their questions in a firm but friendly manner or else forwards the query on to the professor, if she does not know the answer herself. The students only very recently learnt that Miss Watson does not exist; or rather that she is not a real flesh-and-blood person.6

A cause for optimism

The very complexity of education is actually a cause for optimism, and this is for various reasons. Firstly, it makes clear that education is not something you can just ‘do’, almost without thinking. You see this sometimes in television programmes. A famous celebrity is dropped into a classroom and expected to play the role of ‘teacher for a day’. Most of them don’t make a very good job of it. Why? Because it’s not as easy as it looks. The more people understand that education and teaching are complex matters, the greater the likelihood that the image of teachers will improve. The second reason for encouragement, at least in my humble opinion, is the fact that the very absence of simple, all-embracing solutions means that there are many roads leading to Rome. If you look at the results of educational research, you will soon discover that there are a variety of different methods that ‘work’.

Lots of things work, but…

Even so, we need to be realistic. Lots of things work, but not always, not for everyone, not for every purpose and not in every context. I hope that the following two examples will serve to highlight this complexity.

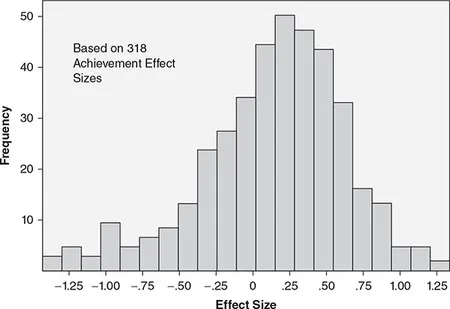

Figure 1.2 Electronic distance learning versus face-to-face instruction: Distribution of effect sizes (Clark and Mayer 2016, based on data from Bernard et al., 2004)

Take a look at the diagram on the previous page (Figure 1.2). It shows the effectiveness of particular courses of study and the extent to which those courses involved the use of online teaching methods.

In this graph you can see an overview of the 318 different effect sizes of studies measuring the different learning effect of electronic distance learning versus face-to-face instruction. With effect size scientists describe the magnitude of the result as it occurs. While in most statistics, there aren’t any negative effect sizes, in discussions about learning negative effects are sometimes used to show that pupils have actually ‘unlearned’. If you look at the graph if you want to know if digital learning is better or worse than face-to-face learning, the answer isn’t clear-cut. The effectiveness results of the courses where the majority of the teaching was given online are to be found on both sides of the results spectrum. In other words, online courses belong in both the ‘most effective’ and ‘least effective’ categories. This means that it is easy to disprove the statement ‘online teaching doesn’t work’ by simply looking at this graphic. It also shows, of course, that purpose, context and approach are all important in achieving success. This example is taken from the seminal work on technology in education by Clark and Mayer,7 in which they take several hundred pages to explain what works, when, where and why (before adding a final ‘maybe’...).

You can apply a similar reasoning to my second example: homework. In recent years, there have been an increasing number of pleas to abolish homework. If you consult John Hattie,8 you will see that homework has a mean effect size of 0.29, which is not brilliant. Hattie only refers to ‘added value’ for scores of 0.40 and above.9 However, it is important to realize that this score of 0.29 is a mean score, an average. If you start to make distinctions within the average, you soon see different results. Take age, for example. The learning effect of homework in primary schools is an abysmal 0.15, but this score increases dramatically as the pupils get older, so that by the time they reach the last two years of se...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Table List

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- 1 Cooking, Medicine and Evidence

- 2 Prior Knowledge: How Learning Begins

- 3 The Subject Matter Knowledge of the Teacher

- 4 Make Them Think!

- 5 Repeat, Pause, Repeat, Linger, Pause, Repeat

- 6 The Importance of Practice

- 7 Metacognition: Teaching Your Pupils and Students How to Learn

- 8 Evaluate and Give Feedback

- 9 Use Multimedia, But Use it Wisely

- 10 Have a Vision (And It Doesn’t Matter Which One)

- 11 Like Your Pupils

- 12 Underlying Themes

- References

- Index