- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aesthetic Labour

About this book

This accessible and exciting new text looks at the implications of aesthetic labour for work and employment by contextualizing debates and offering a critical approach. The origins of aesthetic labour are explored, as well as the relevant theories from business and management, and sociology. Coverage includes key topics such as: corporate strategy; recruitment and selection practices; and discrimination.

Key features include:

- a range of case studies from across different types of organizations and popular culture

- the exploration of topics such as branding, ?lookism?, ?dressing for success? and cosmetic surgery

- suggestions for further reading.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Appearances Matter

Moira was an intelligent, well-dressed and attractive woman in her early 30s. She was the human resources manager of a boutique hotel, Hotel Elba, which counted amongst its guests minor rock stars and celebrities, well-heeled businesspeople and weekend holiday break yuppies. The hotel had an opulent style; all deep, dark colours and rich velvet drapes. Moira was reflecting on her hotel’s hiring policies. She was staring at the company’s recruitment advertisement and explaining that ‘Nicole’, the ‘stylish’, ‘tasty’, ‘caring’ and well-travelled young woman depicted in the advertisement, was meant to epitomise the type of workers that the hotel wanted: ‘At Hotel Elba we didn’t look for people with experience,’ she said, ‘they had to be pretty attractive looking people’. As Moira continued:

The hotel owner is very sticky on the whole image thing … attractive but friendly. There is probably a kind [of] look. It is this kind of not overly done up person but quite plain but neat and stylish. Someone who’s got a nice smile, nice teeth, neat hair and [now laughing] in decent proportion. I wouldn’t go for a fat person. It’s that kind of pure, quite understated look.

Importantly, Moira noted how male employees were subject to similar criteria, with expectations of a ‘neat appearance … clean shaven… [making] an effort to look neat and tidy and presentable’. Using workers who look good and/or sound right is not confined to Hotel Elba; it is now mainstreamed in interactive service organisations in hospitality and retail and, as we discuss later in the book, increasingly beyond. These workers are hired because of the way they look and talk – or can be made to look and talk. Once employed, they are then instructed in how to dress and present themselves, and the use of body language and even speech to further enhance their appearance. For employers, such employees produce a desired style of service. It is what we term ‘aesthetic labour’ and its use is a deliberate managerial strategy perceived by employers to appeal to customers or clients and produce organisational benefit. This book examines this labour, placing it within the context of social and economic trends, how it is manifest in the workplace through the interactions of management, employees and customers or clients, and then, in turn, its social and economic effects.

Discovering aesthetic labour

The origins of our conceiving of aesthetic labour lay in a newspaper job advertisement that overtly stipulated the attractiveness of applicants. It was the early 1990s and we were both working at a university in Preston, in northern England. The town’s history is long and illustrious but by the 1990s it was down on its luck. It had been an ancient market town made into a cotton mill boomtown in the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century. Serious worker unrest followed (Dutton and King, 1981) and Karl Marx and Charles Dickens visited the town to view the proletarian squalor. In the early twentieth century auto plants and engineering firms sprang up in the town. By mid-century, however, the mills had gone and the inland river port closed, and by the 1970s the auto plants and most of the other large employers had also left the town (Lambert, n.d.). De-industrialised, Preston suffered high levels of unemployment into the early 1990s, and unsung haunting melodies of better days gone by hung over the town.

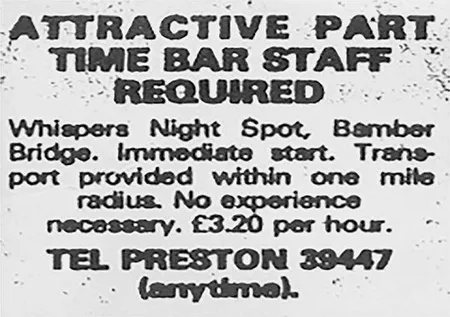

In the midst of this economic gloom a job advertisement appeared in the local newspaper, the Lancashire Evening Post (see Figure 1.1 below). Some employers, it seemed, were still hiring. A local nightclub, Whispers, wanted new bar staff to start work immediately. Experience was not required but Whispers made it clear that it wanted very particular staff: applicants needed to be ‘ATTRACTIVE’ the advert stated in large, bold type.

Figure 1.1 Attractive bar staff wanted

Source: Reproduced with permission from the Lancashire Evening Post (1993), 1 September, p. 12.

The small and particular can have larger meaning and significance (Mills, 2000[1959]), and it was this advert that sparked our sociological imagination. It was a seemingly nondescript advertisement for a part-time, low-paid job tucked away in the back pages of a provincial newspaper, but the employer’s stipulation for attractiveness as the sole hiring criterion opened up big questions about the nature of work and employment in economies increasingly dominated by interactive services such as hospitality and retail. We wanted to know the extent of aesthetic labour in these types of jobs and whether or not it extended beyond them. However, as Mills (2000[1959]: 364) stated, ‘facts and figures are only the beginning of the proper study’. The main interest, he continued, should be ‘making sense of the facts’. Beyond the level of demand for it, we also wanted to know how and why this labour is supplied, developed and deployed – and how it is experienced by workers and its consequences for those workers in an economy dominated by services and a society in which there is now greater emphasis on a person’s looks. It is these questions that we seek to explore in this book. Questions that are crucial to understanding work and employment not just in Preston or even the rest of the UK, but in service-dominated economies throughout the world.

For appearances’ sake

Whilst Preston has many claims to fame, we are not suggesting it is in this town that employers first became interested in and exploited the lure of their employees’ appearance. The aesthetic appeal of workers has not gone unnoticed by employers in the past. As early as the sixteenth century the Society of Jesus – the Jesuits – were keen to recruit potential priests who, in appearance, deportment, conduct and style would not ‘put the public off’, according to Hopfl (2000: 204). The Society looked for candidates with ‘a pleasing manner of speech and verbal facility, and also good appearance in the absence of any notable ugliness’, because the priests’ corporeality was ‘part and parcel of the public face of the Society, its collective self-presentation’ Hopfl states (pp. 204, 205). As the twentieth century unfolded and interactive customer services became more prevalent, private sector employers began to take commercial advantage of employee looks (see for example Belisle (2006) and Benson’s (1983) discussion of the importance of the appearance of female employees in early Canadian and US department stores respectively). Indeed, Mills (1951) identified an emergent ‘personality market’ through which employers bought the personalities of service workers. This personality comprised the attitudes and appearance of these workers, who Mills referred to as ‘the new little Machiavellians’ (pp. xvii) for their manipulative capacities and their ability to ‘sell’ their personalities as part of their work. It is important to note, however, that these employers hired these physically attractive workers and then pretty much left them to get on with their job. It was the workers who first developed and then mobilised and deployed their looks in work – as Mills’ flirtatious female department store worker illustrates in using money from her pay cheques to buy nice dresses that deliberately, ‘focuse[d] the customer less upon her stock of goods than upon herself’ and helped her ‘attract the customer with modulated voice, artful attire and stance’ (p. 175).

Unfortunately Mills’ focus on ‘personality’ quickly narrowed to focus only on workers’ attitudes, analytically ignoring their appearance. The reason might be a lack of employer intervention in employee appearance at that time, for example through training. It was, after all, the 1950s when customer service was still embryonic, as Mills recognised. This partial analysis, however, has continued more recently in Hochschild’s (1983) seminal articulation of emotional labour. Hochschild draws on Mills’ work and also notes the importance of flight attendants’ attitudes and appearance in their interactions with customers for the airlines. ‘Display is what is sold’ (p. 90) Hochschild states, with airline companies seeking to standardise the appearance and transmute the feelings of flight attendants through recruitment and training. However, 30 years after Mills, she also quickly retired analysis of worker corporeality. We explore this important omission in more depth in Chapter 3. Here it is sufficient to note that much current research of interactive service work, framed by the emotional labour paradigm, has remained focused on attitudes rather than appearance – on employee feelings and not their bodies. As such it would be unfair though to single out Hochschild for this analytical myopia. Its cause may be the very shift to services. When it was dangerous and physically demanding, the impact of work on the labouring body was often immediate and visible. With the decline of primary and secondary sectors – coal mining and steel mill jobs for example – and the rise of the tertiary sector and service jobs, the centrality of the body to work and the impact of work on the body have become less visible, and much less analytical attention has been paid to the body at work according to Slavishak (2010).

Slipping under the academic radar in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, aesthetic labour has become mainstreamed on the high street. During this time employers have shifted from simply recognising the commercial utility of employee appearance to now intervening to shape that appearance in order to lever that utility. For example, in 2009, whilst at the same time trying to shake off accusations of discriminating against employees on the basis of physical appearance (Malvern, 2009; Pidd, 2009), fashion retailer Abercrombie & Fitch (hereafter A&F) was still openly recruiting new store employees on the basis of their physical appearance. In 2010 and trading under the name of Hollister, the company opened a fashion retail outlet in Aberdeen in Scotland. At the opening, the company employed two ‘well-toned’ males to stand at the store door dressed in sunglasses, flip-flops and swimwear to welcome the ‘good looking, cool’ customers that it was hoping to attract (Allen, 2010; and see Chapter 7 for a fuller discussion of aesthetic labour in A&F). That these workers are there and made up in the way that they are is a strategy on the part of the employer intended to appeal to the senses of customers: these men are perceived, by their employers at least, to be attractive and their function is to attract customers. As such, standing at the store door, dressed as they are, is an explicit feature of these workers’ waged labour.

The labour in aesthetic labour

This strategy highlights that employers not only need to ensure that workers’ potential to labour is converted into actual labour but also want to determine the nature of that labour. An employment contract enables employers to have the right to direct, monitor, evaluate and even discipline employees – within reasonable limits of course and sometimes mediated by the state and trade unions (Kaufman, 2004) – and thereby set what work is to be done, how it is done and when it is done by workers in exchange for pay. In other words, for employers, it is not enough for workers to labour; how that labour occurs is also important to employers. Moreover, as labour process theory contends, to remain competitive there is a constant need for employers to revise or renew the production of services (and goods). Consequently the wage–effort bargain between employers and employees is dynamic and how labour is expended changes over time.

Drawing on the contributions to Thompson and Smith (2010) we discuss the importance of labour process theory for understanding aesthetic labour in Chapter 3. For Harry Braverman (1974), who is credited with reinvigorating theory of the labour process post-Marx, the analytical starting point was Taylorism or scientific management. In the first decades of the twentieth century and focused on manufacturing, F.W. Taylor was advocating scientific management, and through it encouraging employers to appropriate and transmute workers’ knowledge of the production process in the drive for competitiveness. By mid-century as interactive services were expanding, and for the same reason, Mills (1951) was noting how employers were utilising worker attitudes in the production process, which they bought on the personality market. By the end of the twentieth century employers were intervening to appropriate and transmute these attitudes through feeling rules, and emotional labour was identified by Hochschild (1983) as an important feature of interactive service work. Aesthetic labour represents the attempt by employers to appropriate and transmute workers’ corporeality and again for the same reasons. Put bluntly, employers once sought to control the heads and then hearts of workers; now with aesthetic labour, they seek to do likewise with the bodies of workers. As Wolkowitz (2006: 175) has noted, bodies are not just used in the capitalist labour process, this labour process determines which bodily capacities are recognised and recompensed. Aesthetic labour is therefore borne out in the wage–effort bargain, as employers need to secure competitiveness in the market and the service interaction between employee and customer. With employers aiming to create an appealing service encounter for customers, workers are hired because of the way they look and talk; once employed, they are told what to wear and how to wear it, and instructed how to stand whilst working and even what to say to customers. An important point to note here is that aesthetic labour includes but extends beyond the ‘look’ of employees, even if that ‘look’ has attained primacy in Western culture because of the emphasis on the visual senses, a point we discuss further in Chapter 2.

To understand how these bodies are made up, and appreciating that labour power is reproduced within and outside the workplace, we draw on Bourdieu’s (1990, 1992, 2004) theory of practice. In this theory, and grossly simplifying at this stage, Bourdieu argued that each social class teaches or socialises its offspring how to think and be in the world in its own image. These ‘meaning-giving perceptions’ and ‘meaningful practices’ (or ‘doxa’ and ‘hexus’ respectively) are what Bourdieu calls ‘habitus’, and are characterised by embodied dispositions, including body language, dress and speech (2004: 170). These dispositions are transposable in that they can be active in different fields, e.g. the home and workplace. In this sense workers bring their habitus to the workplace where it is mobilised, deployed and commodified by employers as part of the wage–effort bargain. Whilst Bourdieu’s theory is focused on class reproduction, we use it to explain how employers want employees to inhabit that organisational context – though later in the book, in Chapter 7, we also reveal how many interactive service organisations are choosing, or discriminating in favour of, workers with middle-class habitus. Employers, not just families, can develop and mobilise and deploy dispositions. As we first defined aesthetic labour in Warhurst et al. (2000), it thus not only involves employees selling their corporeality to the employer, it also refers to that corporeality being ‘made up’ by the employer to embody the desired aesthetic of the organisation and is intended to provide commercial benefit. These embodied dispositions are, to some extent, possessed by workers at the point of entry into employment. However, and a key point, employers then mobilise, develop, deploy and commodify these dispositions through processes of recruitment, selection, training and management, transforming them into a ‘style’ of service encounter that appeals to the senses of the customer. As explained in Chapter 3, however, this definition has been modified in light of subsequent research.

From shipping to shopping, from mills to malls

Whilst a beauty premium exists that rewards good looking employees in jobs across manufacturing and services (e.g. Hamermesh, 2011; Harper, 2000; Sierminska, 2015), the emergence and mainstreaming of aesthetic labour as a managerial strategy cannot be disentangled from the increase in and increased importance of interactive service jobs. The service sector now accounts for over 80 per cent of all jobs in the UK (House of Commons Library, 2019), with hospitality and retail providing around six million jobs (Rhodes, 2018; UK Hospitality, 2018).

Within this context of the growing importance of service sector employment, aesthetic labour’s existence became more obvious to us when we both moved for new jobs to Glasgow in the mid-1990s. Glasgow is now a city with a vibrant services economy, which in large part contributes to it being ranked in 2019 by Time Out magazine as one of the world’s top ten cities to visit (Harrison, 2019). The service sector accounts for 84 per cent of jobs in Glasgow, with retail, hospitality and tourism designated as key sectors in the city economy (Glasgow City Council, 2016; Invest Glasgow, 2018a, 2018b). However, when we started to develop research on aesthetic labour in the Glasgow of the late 1990s, the city – as with other de-industrialised cities in northern Britain such as Manchester, Newcastle, Sheffield and Leeds – was still undergoing a process of urban regeneration, with shopping replacing shipping, and malls replacing the mills. Indeed, as we were to discover it was increasingly seen as an exemplar of services-driven economic regeneration. The isolated advert in Preston was commonplace in Glasgow: local newspapers, such as the Glasgow Herald, Sunday Herald and Evening Times, frequently featured job advertisements that included reference to employee appearance. In retail for example, one stipulated that applicants had to have ‘high standards of personal presentation’; in hospitality, another listed the need for an ‘immaculate appearance’. Indeed, these local evening and daily newspapers were replete with ‘upmarket’ retail and hospitality employers’ job advertisements signalling the importance of applicant appearance. Many advertis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Table List

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Appearances Matter

- 2 The Aestheticisation of the Economy and Society

- 3 If You Look the Part, You’ll Get the Job

- 4 Ready to Workwear

- 5 Body Talk

- 6 Irritable Vowel Syndrome

- 7 Beauty and the Beast

- 8 The Future of Aesthetic Labour

- Appendix: Brief details of the research projects

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Aesthetic Labour by Chris Warhurst,Dennis Nickson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.