eBook - ePub

Reflections on Gifted Education

Critical Works by Joseph S. Renzulli and Colleagues

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reflections on Gifted Education

Critical Works by Joseph S. Renzulli and Colleagues

About this book

In this compelling book, more than 40 years of research and development are highlighted in a collection of articles published by Joseph S. Renzulli and his colleagues. Renzulli's work has had an impact on gifted education and enrichment pedagogy across the globe, based on the general theme of the need to apply more flexible approaches to identifying and developing giftedness and talents in young people. This collection of articles and chapters has strong foundational research support focusing on practical applications that teachers can use to create and differentiate learning and enrichment experiences for high potential and gifted and talented students.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reflections on Gifted Education by Joseph Renzulli,Sally M. Reis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Inclusive Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

A General Approach to the Study of Giftedness and Overview of Major Models

CHAPTER 1

Examining the Challenges and Caveats of Change in Gifted Education

University of Connecticut

DOI: 10.4324/9781003237693-1

Conflicts between incompatible, staunchly held, sincere beliefs make up what we may call the little wars of science, little wars which, except for size and consequences differ in pattern no whit from the big wars between nations.—Edwin G. Boring, History, Psychology, and Science

Introduction From Joe

Changing beliefs, practices, and policy in any field are always a challenge. You need only look at the biographical accounts of people in all fields of human endeavor who have tried to make changes to understand how professionally risky even mild recommendations for changing the status quo can be. The “little wars” that Boring mentions in the above quote are necessary for our field to grow, but the value of change must go beyond conflicting papers, competing theories, and passionate seminar debates. The real payoff of any new idea is how it affects the practices that take place in the classrooms and programs that serve the young people who are the object of our work in gifted education. It is easy to criticize an idea or theory, but practical applications yield data that are subject to a wide range of evaluative criteria that go beyond unverified speculation. The proof of the pudding is in the eating, and therefore we have tried to include in this book as much practical information as is possible.

Although my collective work is best known for the systems and models for change that my colleagues and I have developed over the years, an equal and perhaps even greater focus has been devoted to how practical materials, strategies, and professional development interact with research-based findings to bring about the change processes. This chapter describes “where I’m coming from” so far as the always-challenging process of change is concerned, how one goes about introducing new ideas in the field of gifted education, and dealing with the inevitable criticism that usually accompanies new ideas, particularly those that challenge the services that traditionally have been provided in gifted education programs. This chapter hopefully will set the stage for the chapters that follow.

My former advisor and I got together over a bottle of bourbon for late-night discussions at almost every conference following the completion of my doctoral degree at the University Virginia in 1966. Dr. Virgil S. Ward was the most respected and best-known theorist in the field at the time and as the years went by and my work started to gain some attention, he would always ask, “How do you account for the popularity of your work?” Implicit in his inquiry was that “popularity” was not necessarily a good thing if the work was not “theoretically based” and he was fond of citing many other “trendy” educational programs that did not have what he called “a strong underlying theory.”

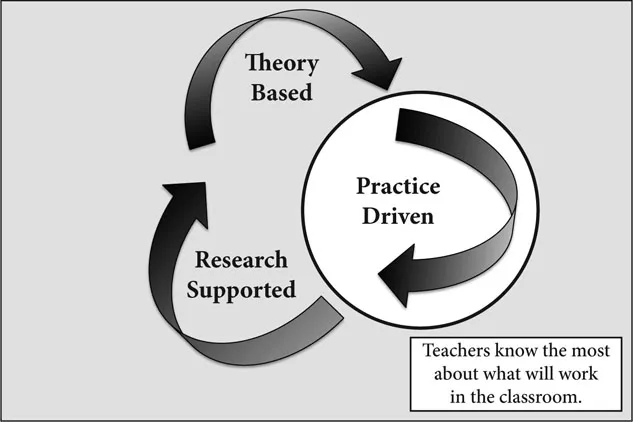

Many others have asked the same question over the years. Although there is no easy answer to the question about popularity, an oversimplification might be that I believe practice should drive theory development rather than the other way around and that research should be a part of an ongoing process directed toward theory development. The Practice-Research-Theory Cycle depicted in Figure 1.1 is an approach that has worked for me because the ultimate consumer or end-user of my work has been the education practitioner and ultimately, students in school learning situations. When all is said and done, most of my approach to change is based on the belief that teachers know the most about what will work in classrooms. Like all academicians, however, there is a need to gain respect among the scholarly community and administrators who always raise the question, “Where is the research?” If my work has achieved “popularity” beyond the common sense that it makes to teachers, it is also because there are volumes of easily accessible research studies underlying the approaches I have recommended.

However, the number of articles in refereed journals or presentations at prestigious research conferences, while important for academic respectability, are only important to me as part of the Practice-Research-Theory Cycle for making changes in schools and classrooms. Thus, for example, when I argue in the Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness theory that “task commitment” based on strong interests is an essential part of developing high-level talent, the pragmatism that is an equally important part of my way of thinking led to years of research development on a series of instruments called Interest-A-Lyzers.

Although I have contributed some major theories (or models) to the field, all of the theories had their origins in firsthand experiences from my years in the classroom and the countless brilliant teaching practices that I have observed over the years on the parts of persons with whom I have had the opportunity to work. These practices usually resulted in one or more research studies to provide the empirical support that is necessary in the evidence-base orientation so pervasive in fulfilling the criteria for academic credibility. The research enabled us to advocate or make suggestions for practice and additional research, ultimately leading to the formulation or reexamination of a theory (or model) that would both guide practice and generate further research.

If I were to come back in another life, I would like to spend a majority of my time studying the elusive process of change. How does any idea become popular, gain academic respectability and sustainability over an extended period of time, and produce verifiable results in planned learning situations? What influences do personalities, politics, and purse strings have in the change process? How do the sights, sounds, and smells of real classrooms figure into the change process and how do teachers’ ways of knowing impact their acceptance of a change initiative? And how does one respond to critics or questions about the relationship of our work with competing theories or guides for gifted student identification and program development? How should one respond to an article entitled, Renzulli-itis—A National Disease in Gifted Education (Jellen, 1983)? These last two questions reflect what E. G. Boring referred to in the above quote as the “little wars of science” and they have made my work interesting, challenging, and even fun. Even the severest criticism has provided an opportunity to reflect and examine the ways to make our work better. Openness to critique, criticism, and challenge undoubtedly threaten one’s self-concept, but it also gives rise to the self-efficacy necessary for the courage to move forward.

The Challenges of Change

The real difficulty in changing the course of any enterprise lies not in developing new ideas but in escaping old ones.—John Maynard Keynes, English economist (1883–1946)

The Practice-Research-Theory Cycle is all about the process of change: policy change, organizational change, and perhaps most importantly, change in the attitudes and behaviors of practitioners directly responsible for implementing a theory-driven method that differs from current practice. If policy adoption, organizational sponsorship, and practitioner support are all present, change is likely to take place more smoothly than if one element is missing. In popular parlance, both “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches are most effective in bringing about any kind of social, political, or educational change Purely top-down change, whether or not it is theory driven or research supported, will not achieve prolonged implementation if the power elite dictating particular changes in a school or district do not win the “minds and hearts” of teachers and principals. The main strategy for winning the minds and hearts of leaders and practitioners, and for bringing about the sustained implementation of new ideas is persuasion.

Persuasion, a prima facie form of salesmanship, is dependent upon effective communication, which in turn is a function of the exchange of relevant information between and among particular constituencies. Organizations such as school districts and state departments of education are concerned with issues such as research support, tangible benefits at low costs, minimal disruption of existing routines, how the change fits in with already adopted initiatives, and political considerations related to equity, public relations, and popular support.

Practitioners (e.g., teachers, principals, school psychologists) on the other hand, are more concerned with how the proposed change will affect their day-to-day work and how much time and new knowledge will be required to implement a new initiative. Practitioners, however, also have informal “theories” and beliefs about the best ways to provide educational services, and in this regard they may be a more sophisticated and demanding audience than policy makers or organization managers. Practitioners always care about whether a proposed change makes sense in terms of what they believe, how much work will be involved, and what the best ways are to accomplish a particular objective.

These differences in the target populations for persuasive activity mean that strategies for change, and especially the genre of communication, must be carefully crafted to meet the needs of various audiences. An article or workshop for teachers, for example, should include some practical theory conveyed through clearly illustrative examples that answer questions about why they should consider a proposed change. And some information about research results, based on data from schools that resemble the workplace of teachers (rather than laboratory experiments with college sophomores), is also useful in helping them to reach conclusions about adopting a particular strategy. But the essence of persuasive communication for teachers should mainly address concerns about what is expected from them in bringing about a proposed change, how these expectations relate to their own beliefs and daily activities, and what practical materials and strategies can be provided that will make their implementation easier.

Approaches to Promoting Change

All theorists are promoters and proselytizers, but most theorists leave practical applications to others. This orientation is especially prevalent among psychologists, even if they believe that their work has applications in practical education settings: “Here is my brilliant idea—I leave its implementation to you educators” (condescension sometimes implied). Because education is my major affiliation for both theoretical and applied work, and having an impact in schools a major professional goal, one of the characteristics of my work is that it has proceeded simultaneously along both theoretical and practical lines. For better or worse, I have never been content with developing theoretical concepts without devoting equal or even greater attention to creating instruments, procedures, staff development strategies, or instructional materials for implementing the various concepts. This approach has both advantages and disadvantages! An eye toward implementation enables theory testing in practical settings—the kinds of places for which the work was intended and where the uncertainty of personalities, politics, and variations among schools and populations allow examination of impact in the so-called real world. The disadvantage is, of course, less than rigorous experimental control and thus the susceptibility to design-related criticisms.

A second advantage of pursuing a Practice-Research-Theory Cycle is that it has enabled me to stay in touch with what happens in real schools and classrooms and the practical and political challenges of people working in them. Theory in an applied field doesn’t have much value if it is not compatible with real-world conditions, such as how schools work, teachers’ ways of knowing, or the politics of “innovation.” People or committees who haven’t worked in a classroom for a long time (if ever) make far too many education policy decisions! As Dwight D. Eisenhower noted, “Farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil, and you’re a thousand miles from a cornfield.” Our main concern has been practices that can reasonably expect to endure beyond the support usually accorded to pilot or experimental studies or the guiding influence of a patron saint that originated or shepherded the program in its initial implementation. Some of my greatest disappointments have been to see excellent services developed as part of a research study, but lack sustainability when the research project is concluded or to see a great program implode when a patron saint or knowledgeable and committed leader leaves the program. It is for this reason that we have built teacher leadership components into our staff development services and program monitoring devices that we call “friendly validation.” The opportunity to generate research data can lend credence to the theory and point out directions where additional work needs to be done in both theory development and, perhaps even more importantly, in fitting theory-guided practices into the complexity of diverse school settings. In fact, the evolution of my work over the years is a direct result of these realities, for it is from direct experience that my ideas have taken new directions.

A third advantage of a Practice-Research-Theory approach is that it has afforded me the opportunity to collaborate with exceptionally talented practitioners, many of whom have expanded both the theoretical and practical dimensions of the ideas and suggested further needed research to enhance understanding, application, and credibility. One of the main lessons learned from my practice to theory approach is that the best ways to bridge the frequently lamented theory-into-practice gap is for the ivory tower people and the people in the trenches to listen to one another. And good listening means paying attention to what is not said as well as that which is spoken.

The negative side of a combined Practice-Research-Theory approach is the vulnerability of partially or poorly implemented practices. In most cases, it is the implementation rather than the theory that is the object of scrutiny. When I visit classrooms, for example, in which every student has produced cookie cutter copies of the same project while simultaneously claiming that these projects are examples of what I have defined as Type III Enrichment (i.e., individual and small-group investigations of real problems), it reminds me of the quote about the shadow that falls between the idea and the reality. Nevertheless, even negative experiences have value. Mainly, they point out that the originator of the theory has not engineered the proper conditions for implementation, communicated effectively with practitioners, provided the appropriate training and resources, overestimated what works in the real world, or all of the above! Many innovative programs work well at the experimental level because supplementary funds and highly committed research teams and patron saints support these factors. The bench chemist might be able to make a new drug work in an experimental setting, but producing millions of gallons for wholesale use is the job of chemical engineers. I view theory development that is paralleled by practical procedures for implementation as the best combination of ideas and engineering.

The result of my “engineering” has been two major theories (the Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness and the Enrichment Triad Model) that will be overviewed in Chapter 2 and covered in greater detail in Parts II and III of this book. Part IV of the book will cover related subtheories that are designed to enhance the overall talent development model that has been the theme of my work.

The Rocky Road of Educational Change: Circa the Late Sixties and Early Seventies

Obstacles related to bringing about educational change can occur on multiple levels. In the late 1960s, when I first began work on the Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness and the Enrichment Triad Model, I never dreamed: (1) that my work would become popular enough to form the basis for an invitation to prepare this book, (2) that this work would be widely used in schools throughout the world, and (3) that it would become the basis for a good deal of controversy in the field. This work was greeted by a less than enthusiastic reception from the gifted establishment of the time including rejections of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents Page

- Preface An Introduction, Some Personal Stories From Some Very Special People, and a Reader’s Guide

- Part I A General Approach to the Study of Giftedness and Overview of Major Models

- Part II Conceptions and Identification of Giftedness

- Part III Systems and Models for the Development of Giftedness and Talents

- Part IV Implementation Components and Strategies

- Part V Contemporary Issues, Challenges, and Commentary

- About the Editor