- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

The second edition of Doing Ethics in Media continues its mission of providing an accessible but comprehensive introduction to media ethics, with a grounding in moral philosophy, to help students think clearly and systematically about dilemmas in the rapidly changing media environment.

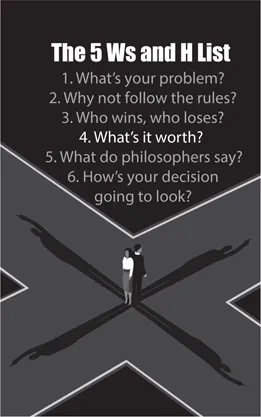

Each chapter highlights specific considerations, cases, and practical applications for the fields of journalism, advertising, digital media, entertainment, public relations, and social media. Six fundamental decision-making questions—the "5Ws and H" around which the book is organized—provide a path for students to articulate the issues, understand applicable law and ethics codes, consider the needs of stakeholders, work through conflicting values, integrate philosophic principles, and pose a "test of publicity." Students are challenged to be active ethical thinkers through the authors' reader-friendly style and use of critical early-career examples. While most people will change careers several times during their lives, all of us are life-long media consumers, and Doing Ethics in Media prepares readers for that task.

Doing Ethics in Media is aimed at undergraduate and graduate students studying media ethics in mass media, journalism, and media studies. It also serves students in rhetoric, popular culture, communication studies, and interdisciplinary social sciences.

The book's companion website—doingethicsin.media, or www.doingmediaethics.com—provides continuously updated real-world media ethics examples and collections of essays from experts and students. The site also hosts ancillary materials for students and for instructors, including a test bank and instructor's manual.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

The Fourth Question

What’s It Worth?

Prioritize your values—both moral and non-moral values—and decide which one(s) you will not compromise.

- ➤ Chapter 7 tussles with insights from moral philosophers and moral psychologists who have explored the nature of values and value systems, and it applies these insights to mass media. By reviewing media ethics codes and media behavior, you should come to appreciate the complicated mix of individualized and collective values driving the media machines. The chapter also notes how media practitioners constantly juggle their own values—and those of their institutions—with the values of their clients, sources, subjects, and audiences.

- ➤ Chapter 8 investigates the philosophic and pragmatic nature of truth telling. Almost all media value truth telling—some entertainment media being the understandable exception to the notion. We consider some limits to getting it right: how inherently elusive truth is, how it is gathered and disseminated selectively, how it is balanced against equally compelling values, and how general semantics can help us understand the use and abuse of truth claims.

- ➤ Chapter 9 treats persuasion and propaganda as matters of value. We recognize the significant role of advertising, public relations, and other forums for advocacy—and information— in contemporary life. The chapter offers a model for ethical advocacy, recognizing the legitimacy of selective truth telling and loyalty to clients. It approaches propaganda as an inevitable component of media, and it suggests that sophisticated consumers and producers of persuasive messages should be wary of closed-minded, propagandistic advocacy.

- ➤ Chapter 10 moves to the value of privacy, which requires a never-ending balancing act in media: We consider differences in the legal right to know, and the ethical dimensions of the “need” to know and the “want” to know. We think about how social media and ubiquitous marketing may have irrevocably altered our expectations of privacy. Encroachment upon individual moral autonomy continues to highlight today’s arguments about balancing privacy against other fundamental values.

7 Personal and Professional Values

- ➤ Defines the nature of values as described in social science and humanities disciplines.

- ➤ Explores codes of ethics as documents that describe values in media.

- ➤ Considers the extent to which values are relative or universal.

- ➤ Introduces the basics of systematic values inquiry, an exercise that can help you determine your values.

- ➤ Uses these insights to assess values in media ethics codes and policy statements.

- ➤ Invites you to resolve values issues found in media cases.

Defining Values

What Values Are

- ➤ “a thing or property that is itself worth having, getting or doing, or that possesses some property that makes it so,” and that a value “belongs to anything that is necessary for, or a contribution to, some living being or beings’ thriving, flourishing, fulfillment, or well-being” (Bond, 2001, p. 1745).

- ➤ “an enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state of existence” (Rokeach, 1973, p. 5).

- ➤ “a conception of the desirable that guide the way (people) select actions, evaluate people and events, and explain their actions and evaluations” (Schwartz, 1999, p. 24).

- ➤ the standards of choice that individuals and groups use to seek meaning, satisfaction, and worth. They are prima facie (Latin for “at first sight”) variables that undergird principled judgments, decisions, and actions (Pojman, 1990). They can be ends to themselves, or a means to those ends.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Case Studies

- Welcome to the Second Edition

- About the Authors

- Introduction: Thinking About Doing Ethics, and the “5Ws and H” List

- The First Question: What’s Your Problem?

- The Second Question: Why Not Follow the Rules?

- The Third Question: Who Wins, Who Loses?

- The Fourth Question: What’s It Worth?

- The Fifth Question: What Do Philosophers Say?

- The Sixth Question: How’s Your Decision Going to Look?

- Glossary

- References

- Permissions

- Index