- 340 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book, first published in 1968, examines the disastrous defeat suffered by inexperienced American troops, newly landed in North Africa, at the hands of Rommel. The news of Kasserine shocked the United States militarily and politically, and led to swift changes in equipment and tactics. This book traces the battle through to its aftermath in 'a remarkable piece of battlefield investigation' ( Manchester Evening News ).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rommel's Last Victory by Martin Blumenson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I THE SETTING

1

“Psychologically,” a master once wrote, “it is particularly unfortunate when the very first battle of a war ends . . . [in] a disastrous defeat, especially when it has been preceded by . . . grandiose predictions. It makes it very difficult ever again to restore the men’s confidence.”

The psychologist was Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, one of the astute German generals of World War II. What he said applied to the Americans.

There had been “grandiose predictions” of swift victory — the result of the landings in North Africa. The troops coming ashore gained an easy triumph because they met halfhearted opposition from French soldiers caught in an agonizing dilemma between duty and desire, but in their exultation they overlooked the reason for their quick success. Certainly, the Americans thought, along with their people back home, we have but to appear and the enemy will be terrified and fall before us.

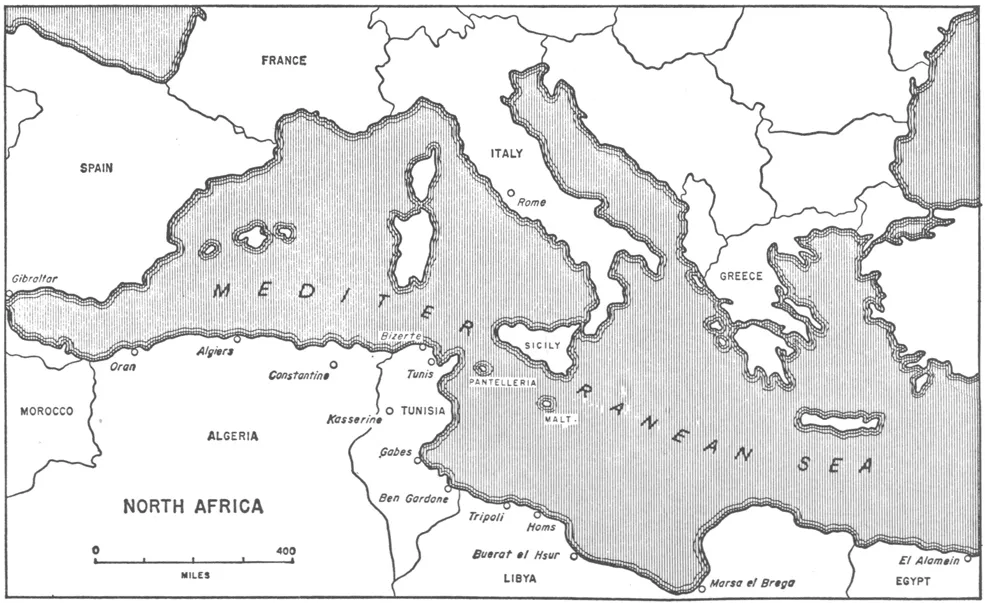

And suddenly there was “a disastrous defeat” — inflicted by the master himself. The blow sent the Americans reeling back in Tunisia, more than fifty miles across the parched plain of Sbeitla between the mountain passes of Faid and Kasserine.

The news of Kasserine went halfway around the world and struck the United States with the blast of a tornado, scattering illusions and leaving in its wake the devastation of a numbing consternation and the shock of disbelief.

To the American people, the event was incredible. It shook the foundations of their faith, extinguished the glowing excitement that anticipated quick victory, and, worst of all, raised doubt that the righteous necessarily triumphed.

How could the forces of evil win over the youth of America? How was it possible for the oppressors of Europe, the soldiers of tyranny and darkness, to destroy the crusaders of freedom and liberty?

Like the inexplicable reverses suffered by earlier Crusaders in North Africa at the hands of the Sultan’s paladins, Kasserine made no sense. The confused picture of havoc at Kasserine flashed across the American consciousness like a nightmare.

The start seemed trifling in February, 1943, when “German tanks, infantry and artillery,” Drew Middleton reported in the New York Times, “brushed aside a small French force defending Faid pass . . . with great gallantry.” The pass had strategic significance, but the German gains were slight, nothing more than an effort to secure the flank of Rommel’s army in the Mareth Line by keeping the Allied army in Tunisia off balance.

There seemed little to fear as a calm descended over the battlefield.

The quiet lasted two weeks.

Then came the eruption, “sledgehammer blows,” the papers reported, driving the Americans back, compelling them to abandon their airfields, to burn their supplies, to flee for their lives.

Officials in Washington tried to be reassuring: the setback, they announced, was only a local retreat.

But soon thereafter, headlines admitted that Rommel had taken three more towns, had subjected the Americans to a five-day mauling, and had driven across Tunisia to come close to Algeria.

Speaking at his weekly press conference in Washington, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was candid. He admitted “substantial casualties, both in personnel and equipment.” He called the situation “a sharp reverse.” He termed the development “a serious local setback” that should be neither minimized nor exaggerated.

But he also said, curiously enough, that Kasserine was “a not unexpected development.”

Had the Americans, then, expected the defeat? To some observers, Mr. Stimson’s statement sounded like an apology for a mistake that was recognized while the error was being made.

The “local setback,” editorialized the New York Times, could hardly obscure the fact that the Germans had scored a victory of considerable importance to their whole military and political strategy. Despite a forced retreat across fifteen hundred miles of the desert in Libya, Rommel had somehow found the strength and the energy to turn and leap against the Americans. His success delayed the course of the entire war. The Germans would now be able to consolidate their hold on Tunisia. They would have more time to prepare their defenses along the European periphery and crush guerrilla fighters in France and the Balkans. The Allies would have to postpone their invasion of northwest Europe. The conquered nations would have to wait longer for their deliverance.

“How,” asked the Times, “could these setbacks arise [three months] after the brilliant execution of the [North African] landing?”

How indeed?

Had political squabbles over fictitious issues deflected attention from military tasks? Could the Axis be defeated only by an overwhelming superiority of men and materiel in North Africa? Were the American troops too inexperienced for the Axis veterans? Were “our boys” too soft to stand up to the thugs? Or was there something else?

The questions appeared to be answered a week later as the Secretary of War held his usual press conference: “‘Clear-Cut Repulse’ in Tunisia Dealt to Foe, Stimson Asserts.” Rommel was withdrawing. The Americans had met the challenge at Kasserine and, according to Mr. Stimson, “came back with a vigor which the Germans were unable to withstand.”

In short, the bad guys had knocked down the good guys. And then, as in the movies, the good guys got up off the ground and thrashed the bullies.

The American dream remained intact. The facile, phony script explained everything.

Yet the bad moment stayed too, never quite forgotten, rather pushed aside, replaced by better images of strength and purpose, courage and valor, know-how and confidence. Quiet toughness rather than bluster.

The outcome was more than a bad memory, more than an uncomfortable sensation. The crushing defeat swept aside the illusions of a time of innocence. Complacency at home and on the battlefield vanished. Kasserine, Mr. Stimson declared, “serves to remind us that there is no easy road to victory and that we must expect some setbacks and considerable casualties. We will not have an easy nor a quick victory.”

The war would continue for more than two more years. As the Secretary said, there would be additional setbacks and casualties. But Kasserine had shocked Americans at home and overseas into an awareness of the grim and brutal facts of war.

They learned some unpleasant but valuable lessons — and quickly. They discovered the terrible ignorance bred of inexperience, the high cost of poor equipment, the tragic effect of sterile bickering among themselves and their allies, and the need of a special kind of man for leadership in battle.

In a country strange and mysterious to most Americans, where the squalor of life made the civilization of a Roman province two thousand years earlier seem resplendent, where Arabs in rags rode half-starved camels and donkeys across a barren and eroded land, where a field full of marble fragments, tumbled about a solitary arch or portal still standing, marked an ancient forum — in that part of the world where Numidi-ans, Berbers, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, and Turks had fought and plundered, American soldiers learned the trade of war at the hands of a master craftsman, who showed them, by the disaster he wrought, the extent of their mismanagement and inefficiency.

What happened, and why?

2

It would have been difficult to find a more captivating villain — handsome, buoyant, talented, a husband and father who adored his wife and young son.

He led the English not so merry a chase, kept a good part of North Africa in turmoil, and threatened for two years to smash one of the pillars of British empire and power, the Middle East. Yet his opponents admired Rommel.

No Nazi, he was a professional soldier uninterested in politics until much later in the war, too late as it turned out. Yet his implication in the plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler — he was an uncomfortable conspirator — and his forced suicide would make him even more attractive to his adversaries.

He compelled respect because he regarded the exercise of arms as an honorable métier, without blind hatred or vulgar disrespect for the enemy; because he scrupulously followed the rules of conduct laid down in an earlier age — and perhaps outmoded in the twentieth century — for officers and gentlemen; because he inspired his men and was considerate of them, leading them personally on the field of battle where the action was critical and the danger real; and because he worked hard at his profession and was good at it.

A pity, some said grudgingly in the Allied camp, that he was on the other side.

Some of his colleagues who regarded the officer corps as a monopoly of the Prussian aristocracy denigrated his accomplishments because he was only a middle-class Württemberger.

Yet Hitler, who was only an Austrian, recognized Rommel’s proficiency and fostered his career. He made Rommel a colonel in 1939, a major general a year later, a field marshal in 1942, and decorated him with the senior grade of the Knight’s Cross, the highest German military award.

A leading exponent of the blitzkrieg theory, Rommel executed it with remarkable results. In employing that hard-hitting combination of rapidly moving weapons — the tank, the airplane, and motorized infantry — he showed his genius in his power of imagination to create surprise, to produce the unexpected. He upset his enemy by mobility and speed, motivated by an audacity that was shrewdly calculated rather than reckless or hotheaded.

Originally an infantryman, he took command of an armored division in February, 1940, during the so-called phony war, and a few months later he was in the forefront of the breakthrough that brought Germany heady victory and France dismal defeat.

At the beginning of the following year Rommel was in North Africa. There he commanded a relatively small German force called the Afrika Korps that Hitler had sent to help his friend, Benito Mussolini.

Mussolini had entered World War II late. He waited until Germany had mortally wounded France before delivering the stab in the back. Then, while Hitler initiated the Battle of Britain to bring the English to their knees, Mussolini waged what he termed a parallel war, embarking on what was to be a glorious adventure in Africa: the restoration of the old Roman Empire. From the Italian territory of Libya he decided to march to the Nile and conquer Egypt.

His army in Libya of 250,000 men had few mechanized vehicles and only obsolete weapons — light and underpowered tanks and trucks, artillery pieces dating from World War I, old-fashioned antitank and antiaircraft guns, outdated rifles and machine guns — but had succeeded against primitive African tribesmen. Against the handful of British troops in Africa and the Middle East, the triumphs continued, and the Italians moved into Egypt. There they had to stop and await additional supplies — gasoline, ammunition, rations, clothing, and the other items needed by units in the field.

They waited in vain. Not only was Italy ill-prepared to furnish the economic requirements of modern warfare, but Mussolini was letting his ambition dictate to his good sense. Instead of sending supplies to Egypt, he invaded Greece. Instead of overrunning Greece quickly, he saw his units bog down.

The British, who had meanwhile hurriedly assembled a modern, mechanized army in Egypt — with tanks, airplanes, long-range artillery, and motorized infantry — attacked the Italians in Africa, virtually destroyed them, and drove them out of Egypt.

Mussolini called for help, and Hitler came to the rescue. He dispatched an air force to southern Italy — to protect Axis convoys in the Mediterranean. And he sent Rommel and the Afrika Korps to Libya — to spearhead the ground operations. Acknowledging Mussolini’s paramount interest in that area, he placed Rommel under Italian control.

Though Rommel was supposed to maintain an aggressive defense, he launched an offensive in April, 1941, and swept across Libya to the Egyptian border. “I took the risk against all orders and instructions,” he later said, “because the opportunity seemed favorable.” It was a characteristic statement.

Beyond the border he was unable to go, for he too needed supplies. He too waited in vain. General shortages, the requirements of the Russian front, poor lines of communication, British air attacks against Mediterranean shipping, and disinterest and incompetence in Rome deprived him of the essentials.

Though he was promoted to command a larger force — Panzer Group Afrika, consisting of the Afrika Korps and several mobile Italian divisions — the increased prestige failed to give him the material means to resist a British attack in December, 1941. Preferring to lose part of Libya instead of part of his army, he withdrew from the Egyptian frontier.

Hitler again came to the rescue. To prevent British planes based in Egypt and Malta from destroying Italian ships carrying supplies to Africa, he sent additional air units to Sicily and southern Italy, plus an energetic air force commander, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring.

The senior German officer in the Mediterranean theater, with headquarters at Frascati, near Rome, Kesselring had will and drive, a capacity for organization, a talent for diplomacy, and a thorough knowledge of technical military matters. He was responsible to Hitler for the proper employment of all the German forces in Italy and North Africa; yet for operations, he too, like Rommel, was subordinate to Comando Supremo, the Italian Armed Forces High Command.

Mussolini exercised supreme command in North Africa through Comando Supremo, which issued operational instructions and sent copies of them to Kesselring for his information. Since he had direct communications with Rommel and Mussolini, as well as with Hitler, he was a key figure. In 1942, after Rommel became a field marshal, he too would enjoy the privilege accorded to all officers of his rank of direct contact with the Fuehrer. Thus, by virtue of their direct access to both Hitler ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps

- Part I The Setting

- Part II Faid

- Part III Sidi bou Zid

- Part IV Sbeitla

- Part V Kasserine

- Part VI The Aftermath

- Note

- Chart: The Allied Command

- A Brief Chronology

- Index