![]()

Chapter 1

The World of the Vikings and the Origins of Viking Art

The period of European history that has become known as the Viking Age lasted some 300 years: that is from the late eighth to the late eleventh century AD. Before discussing the art itself, it will be helpful to outline the main areas of Viking settlement and their development during the Viking Age in both Scandinavia and the wider Viking world. For these purposes, ‘west’ is used to refer to the area west of the Scandinavian mainland, encompassing the islands from Britain and Ireland to Iceland and Greenland – and even the coast of North America. The ‘east’ of the Viking world stretched from modern Finland, the Baltic states and western Russia to the areas along the great rivers Dnepr (Dnieper) and Volga.

Scandinavia and the Viking Age

The Viking Age is, as we have seen, a modern concept, but it is the case that by about AD 1100 the Scandinavian homelands of the Vikings had reached the end of their prehistory, entering the European Middle Ages as Christian nation states. That the Viking Age in Scandinavia is to be regarded as the final phase of the Iron Age, rather than as an integral part of the wider medieval period, arises from the fact that it was only on conversion to Christianity that (Latin) literacy became established in the Scandinavian countries. It is true that there were Vikings familiar with the use of runes, but this form of script – intended for carving on wood, bone or stone – was unsuited for lengthy inscriptions of any kind, for which pen and ink were required in order to write upon prepared animal skins, using the Roman alphabet.[4]

Though the Christianization of the Vikings marks the end of the Viking Age, the introduction of Christianity to Scandinavia progressed slowly, with the earliest recorded missionary activity taking place in Denmark in the eighth century. Viking art forms reflect this process in a gradual inclusion of Christian motifs through these centuries. Ultimately, conversion was a top-down process, proceeding most rapidly with the growing power of kings and the resultant centralization of authority, as in the case of King Harald Bluetooth who proclaimed on the runestone that he erected at Jelling, in about 965, that he had ‘made the Danes Christians’.[7, 107] The development of the nation states of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, as summarized below, was fuelled by the burgeoning economy of the Vikings – through their raiding and trading activities, combined with land-taking and the establishment of overseas settlements (see maps pp. 190–93). It is of no surprise therefore that the establishment of towns in Scandinavia presents another defining aspect of the Viking Age.

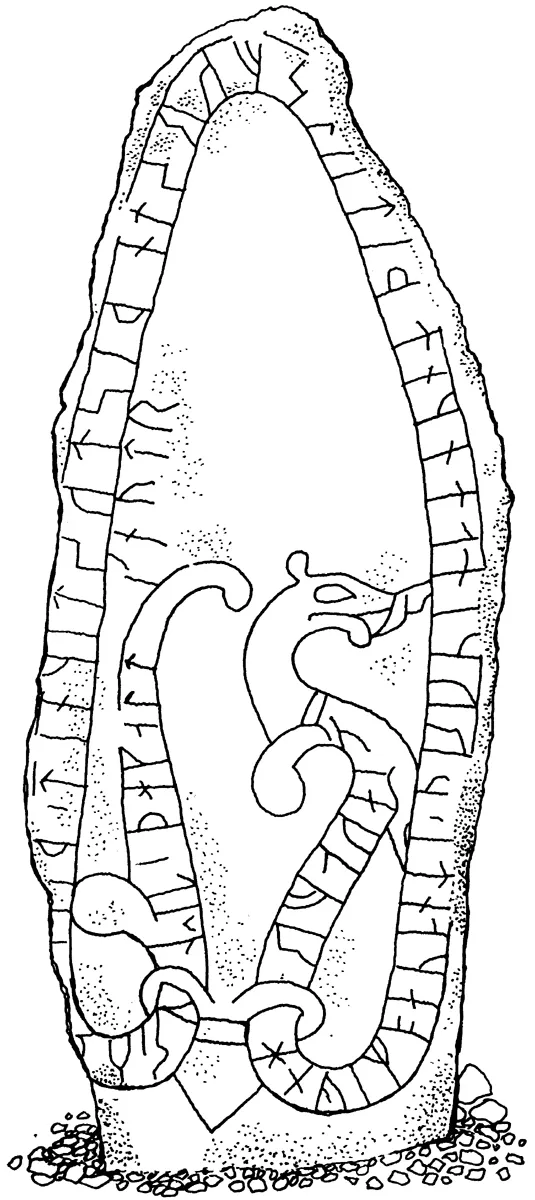

4 The runic inscription on this early 11th-century memorial stone from Yttergärde, Uppland, Sweden, commemorates a man called Ulf who had taken part in three attacks on England (see p. 136).

The pattern of settlement in pre-Viking Scandinavia was mainly one of dispersed farmsteads, which would have been largely self-sufficient. Wealthy chieftains operated from what have become known as ‘central places’: hubs for the local assembly and cult. It was these men who developed the wealth required to build ships and resource the first Viking raids. However, another more peaceful indication of growing economic complexity, especially in southern Scandinavia, was the development of village units capable of producing agricultural surpluses for trading purposes. One response was the creation of regulated seasonal marketplaces, which also served the needs of specialized craftsmen, such as the glass-bead maker and the fine metalworker engaged in the production of jewelry. The growth of such markets (or ‘proto-towns’) was a step in the direction of actual urbanization, with the foundation of towns under royal control.

The Vikings who engaged in raiding and trading across much of western Europe – as also those who followed the eastern routes to the Byzantine empire and the Islamic world of the Abbasid caliphate, with its capital at Baghdad – encountered societies with regulated coin-using economies. At the beginning of the Viking Age in Scandinavia, however, there still existed a prestige economy, with portable wealth measured in gold and silver rings and with exchange based on barter. The development of trade was facilitated by means of a bullion economy in which coins, ornaments and ingots were utilized by weight – being cut up for use as ‘small change’ when this was needed for minor payments.[5] Denmark’s experiment with local coinage in the ninth century, notably at Hedeby, did not take immediate root.[60] It was only during the late tenth and eleventh centuries that kings began to strike what can be considered the first national coinages in Scandinavia.

Before turning to summarize the major developments that took place in Denmark, Norway and Sweden during the Viking Age, it is necessary to mention the high degree of interaction that existed between the Nordic peoples and the Sámi who inhabited a large part of the Scandinavian peninsula during this period. In addition to co-existence along the north Norwegian coast, there was widespread territorial overlap across central Scandinavia. The Sámi were skilled hunters, including for walrus in the north, with access to fine furs, so that in addition to their reindeer products they had available luxury goods for the purposes of trade (in exchange for silver) or, when necessary, for the payment of tribute. Marriage partners were exchanged and the Nordic peoples seem to have held Sámi magical powers in considerable respect. Despite these extensive economic, social and religious contacts, there does not, however, seem to have been much by way of reciprocity in terms of art.

5 Silver hoard found in the Viking Age town of Birka, in central Sweden (D iron dish: 23.5 cm/9⅜ in.), weighing 2.16 kg (4¾ lb). It was buried c. 970 and its contents include Arabic silver coins, together with Scandinavian rings and brooches, some of which have been reduced to ‘hack-silver’, for exchange by weight.

DENMARK

The process of state-formation in Scandinavia was underway earliest in Denmark, the name containing the word mark, which may mean ‘dividing forest’ (in the form of its southern border), combined with the name of the inhabitants Danir. It has been suggested that Denmark’s various territories were already unified into a single kingdom in the eighth century. Dendrochronology supports historical dating for the foundation of the proto-town of Hedeby – or Haithabu (in German) – the predecessor of medieval and modern Schleswig, for which it was abandoned in the 1060s. The earliest manufacturing and trading centre in Denmark was at Ribe, on the west coast of Jutland where it was well situated for participation in the developing North Sea trade, if initially only on a seasonal basis. As Hedeby was becoming the foremost Viking Age town in Scandinavia, other towns developed in Denmark – notably Århus and Roskilde (the latter replacing the ‘central place’ of Lejre as a royal seat). Lund, in Skåne, was a royal foundation of the 990s, which soon overshadowed the nearby ‘central place’ of Uppåkra, becoming the seat of the first archbishop in Scandinavia, in 1103/04.

The Danish nation reached its greatest territorial extent during the Viking Age, when its boundaries extended well beyond those of the present-day kingdom. ‘Old Denmark’ included the southern provinces of modern Sweden: Skåne, Halland and Blekinge. Its sometimes contested southern boundary was marked by a multi-period frontier earthwork, known as the Danevirke (the earliest phase of which seems to have been constructed about AD 700). At the beginning of the Viking Age, the southeastern part of Norway, the coastal region of Viken (around the Vik fjord), was also under Danish control, as was to be the case for much of the Viking Age. An important manufacturing and trading centre established at Kaupang (or Skíringssalr), in Vestfold, flourished during the ninth century.

6 Aerial view of the Danish royal site of Jelling, in central Jutland. The North Mound (in the foreground) contained a burial chamber, constructed in 958/59, presumably for the pagan king Gorm whose body appears to have been transferred to a grave beneath the first timber church (on the site of its medieval stone successor), in front of which King Harald (Gorm’s son) erected a great runestone (ill. 7). The South Mound was also constructed during Harald’s reign.

In addition to the fortification of towns (such as Århus and Hedeby) and the reorganization of the Danevirke, Denmark saw other royal investment in military and administrative works, particularly during the reign of Harald Bluetooth (c. 958–87). Much of the royal necropolis and assembly site at Jelling in central Jutland was planned for him, with the North Mound seemingly constructed for the pagan burial of his father, King Gorm, although his bones were...