It is because you are a Palestinian!”

That was the rationale used by the organizers of a major Christian mission conference in Ireland to explain why they were considering withdrawing their invitation for me to speak at their conference. Their concern was not due to any controversial things I had said or done. It was not related to my theological positions. Their hesitancy for me to participate in the conference simply had to do with who I am and where I come from. I was at fault because I am a Palestinian.

Those words have always haunted me. The ideology behind this kind of judgment has been the basis of how many Christians around the world have judged and treated me and my people. In many Christian circles, my being a Palestinian means that I am dismissed as irrelevant, or even an obstacle to God’s plan for the land of my forefathers. If I choose to believe those “truths,” I must accept that my existence and well-being are secondary in God’s plan. Such beliefs tell me that I do not belong in the land where my forefathers have lived for hundreds, if not thousands, of years because God already decided thousands of years ago who owns this land, and I simply have to accept it!

Being a Palestinian means that I am disqualified from sharing about life in Palestine in many Christian gatherings or even from leading Bible studies in Christian conferences! For many of us Palestinian Christians, these judgments have made us question whether or not God actually loves us as Palestinians. It has caused us to wonder whether God deals with different people in different ways based on their ethnicity, nationality, or religion, or whether we are somehow second-class children of God. Are we at fault because we have the wrong postal address and the wrong DNA?

On the other hand, being a Palestinian means that I am viewed as a demographic threat by the state of Israel and many of its allies. The notion of a demographic threat interprets population increases of particular minorities (usually ethnic) in a certain country as a threat to the dominant ethnic identity of that same country. Palestinians are commonly understood as a “demographic threat” not only by the Israeli government but by many American politicians and Christian groups as well. Some “Christian” groups have even offered to pay us Palestinians money to leave the land and settle somewhere else! Paul Liberman, executive director of the Alliance for Israel Advocacy (a lobbying group established by the Messianic Jewish Alliance of America), explains their policy plan as such, “If there are any Palestinian residents who wish to leave, we will provide funds for you to leave, with the hopes that over 10 years to change the demography of the West Bank towards an eventual annexation.”1 (And that is supposedly a brother in Christ! With brothers like that, who needs enemies?)

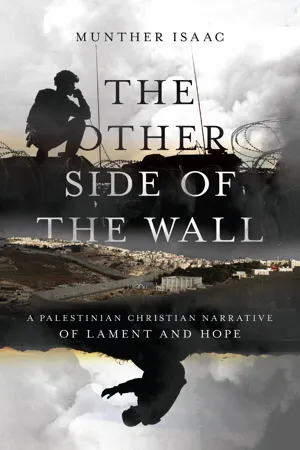

This book is a story of my life journey, with all its struggles and hurdles, in the shadow of these dismissive views and despite them—a journey that led me not only to embrace and celebrate my identity but also see it as part of my calling in life. It is about discovering a sense of calling to envision and work for an alternative reality. More importantly, this book illustrates my journey of discovering that the Jesus of Bethlehem, the son of this land—in his way and teachings and through the kingdom he established on this earth—has shown us the way for a new and better reality, here and now. This is a reality in which faith can move mountains and prepare the path for a better world.

PALESTINIAN AND ARAB

I am an Arab Palestinian Christian. For many, being a Christian and an Arab (let alone Palestinian) is an oxymoron! Many times in the past, when I introduced myself to a Western Christian, I would get the question “When did you convert?”—assuming that, as an Arab, I must have been Muslim. However, Arab Christianity is not the invention of yesterday. In fact, Arab Christianity predates Islam! The church in the East has a long and very rich history.2 There were Arab Christians in the very first ecumenical council of churches in Nicaea in 325 CE. In addition, there have been many profound Arab theologians and apologists throughout the centuries—though one is very unlikely to hear or read about them in Western seminaries and Bible schools.

It is important here to distinguish between Arab and Palestinian and to make clear why I will use the terms Palestine and Palestinian to refer to my land and its people for the majority of this book. Being “Arab” has more to do with belonging to a particular culture, heritage, and language than it does with being the descendants of the ancient tribes of Arabia. Some who would be considered Arab are descendants of these ancient tribes; however, most are not. An Arab is “a person who speaks Arabic as a first language and self-identifies as Arab.”3 Arab identity is defined solely by culture rather than ethnicity or religion.

A Palestinian is not an invention of recent history, though many contend (“convincingly”) with this fact. For them, the term Arab instead of Palestinian is used almost exclusively in political rhetoric surrounding Palestine/Israel to refer to previous inhabitants of the land (Palestinians). However, prominent Palestinian historian Nur Masalha describes the binary of Arab versus Jew in this context as terribly misleading considering that Palestine, until the arrival of European Zionism in the twentieth century, consisted of Arab Muslims, Arab Christians, and Arab Jews. He further elucidates that “the idea of a country is often conflated with the modern concept of ‘nation-state,’ but this was not always the case and countries existed long before nationalism or the creation of meta-narratives for the nation-state.”4 In short, the historical concept of Palestine existed prior to the modern-day understanding of a nation and has continued to shift and evolve throughout history.

Furthermore, Masalha contends that Palestinians have always had a sense of identity that they have related to descent from the geopolitical region identified as Palestine for the last millennia. This was prior to, yet helped shape, the modern concept of a Palestinian nationality, which developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, as articulated by Masalha and others, most notably Rashid Khalidi.5 I use the terms Palestinian and Palestine in this book as both a cultural and geopolitical identity. This Palestinian national identity rooted in the land of Palestine (most of which is now considered Israel) developed in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century yet also has origins in historic notions of Palestine as a country/people.

While I understand it is not conventional for most Christians to refer to this land as Palestine, I invite you to challenge yourself with the alternative perspective I present in this book. In referring to this land as Palestine, I am not confronting Israel in a negating way. And as I will argue at the conclusion of this book, it is my hope that Palestinians and Israelis will one day share this land. Simply put, I am articulating my existence as I have known it and as I and my people think of ourselves—we are Palestinians. I invite you to step into my shoes, and the shoes of countless Palestinian Christians, and seek to better understand my experience and my faith. I ask this of you, not because my experience needs to be at the forefront of any conversation regarding Christianity and the land, but because as siblings in Christ, our journeys and existences are inherently intertwined with one another.

CHRISTIANITY, HISTORY, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAND

Christianity in this land is as old as the Jesus movement. The first church was in Jerusalem and composed mainly of first-century Jews who believed in Jesus as the Messiah. Since then, there has always been a Christian presence in this land. Yet so often, as I already mentioned, people are surprised to know that there are Christians in Palestine. Rather, the surprise should come if we did not exist in Palestine! This is the place where it all started, after all.

The history of Christianity in this land is difficult and complex, and it is closely tied with the history of Palestine. The identity and reality of the church was shaped by the political reality and in particular by who has occupied this land, for this land has always been occupied and invaded by foreign powers. This goes back to biblical times, as the land was ruled by the Assyrians (721 BCE), Babylonians (586 BCE), Persians (539 BCE), and Alexander the Great and the Greeks (333 BCE). In 63 BCE, Palestine was incorporated into the Roman Empire. Between 330 and 640 CE, Palestine was under the Byzantine rule, and Jerusalem and Palestine were increasingly Christianized and established as a place for Christian pilgrimage. In 638 CE, Arabs under the Caliph Umar captured Palestine from the Byzantines.

Between the years 1099 and 1187 CE, the Crusaders established the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was during these years, in fact, that the number of Christians in Jerusalem and Palestine declined in large measures. The Ayyubids under Salah Al Din (Saladin) ended the Crusaders era, and in 1260 CE, the Mamluks succeed the Ayyubids. This was followed by four hundred years (1516–1917) of the brutal rule of the Ottoman Empire with its capital in Istanbul. Many Christians, especially in the last days of this empire, were forced to leave Palestine and settled mainly in Latin America. The Turkish reign ended in 1918 when Palestine was occupied by the Allied forces under British general Edmund Allenby, and Britain established the British Mandate over Palestine.

This short history detailing the reality that the people of this land have never ruled themselves is a crucial element in the shaping of the Palestinian identity. It is also important to understanding this book and the reality and even theology of Palestinian Christians. Mitri Raheb summarizes the history of the land and its people as follows:

Geopolitically, the mountainous land of Palestine is on the periphery of history. For the most part, it has been used by the empires as a battlefield to test and transfer arms and soldiers to suit their powers. . . . The people of this land are trampled over again and again. Each time they try to take a breath, they will receive another blow that drags them through the mud: Their cities get destroyed, burned, and robbed. Their harvests are seized before their time. Their youth are forcibly captured, tortured, displaced, and killed while striving to make ends meet.6

Raheb then contends that it could have been only here that Jesus would launch his “kingdom”—in the land that has witnessed so many violent kingdoms and empires.

Today in the land, the Palestinian community finds itself in two realities. Some are part of the state of Israel (most live in the Galilee area), and some are governed by the Palestinian Authority, while really being under the Israeli occupation. Those who are part of Israel are the ones who survived the war in 1948 and were not expelled by the new government when the state of Israel was created. Today the total number of Palestinians in the state of Israel is about 1.8 million (20 percent of the population), and among them there are 130,000 Palestinian Christians.7 The situation of Palestinians in Israel is best described as second-class citizens in their own homeland. They live under a Jewish state that has just passed a law that declares, “The right to exercise national self-determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish people” (Nation-State Law).

The situation in the Palestinian territories, also known as the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, is more complex and challenging. Around 4.8 million Palestinians, including around 46,000 Palestinian Christians,8 live under the dual reality of a Palestinian government and the Israeli military occupation. In actuality, the Israeli occupation controls every aspect of our lives: land, water, movement, borders, and family reunification, to name just a few. Terms like checkpoints, permits, settlements, and the separation wall define our reality. Injustice and inequality define life in Palestine today.

All of this means that the number of Christians in the land has declined considerably. People, especially young families, both Muslim and Christian Palestinians, are leaving the land and looking for a better life elsewhere. They are seeking opportunity, equality, and freedom, which is simply not available to them in Palestine.

GROWING UP IN BETHLEHEM

I was born in Bethlehem in 1979. When people from around the world hear that I am from Bethlehem (and after I explain that I am talking about the real Bethlehem, not the Bethlehem of Pennsylvania), they often respond with great excitement, “Wow, it must be great to have been born in the place where Jesus was born and to live where he lived!”

But for me and most Bethlehemites from my generation, growing up in Bethlehem was not really about growing up in the place of Jesus’ birth. As children and teenagers, we did not wake up thinking of how blessed we were to live in the land where Jesus walked! In fact, I cannot remember my parents ever taking me to visit the Church of the Nativity—the place where it is believed Jesus was born. The first time I can remember visiting the Church of the Nativity was when my aunt who lived in the United States came to visit us!

“Blessed” was not the first thing that came to mind to describe how we felt about our reality. Growing up in Bethlehem was full of challenges. Our reality was, and still is, defined by the Israeli military occupation of our land. When I was eight years old, the first intifada erupted.9 These were years of weekly, if not daily, demonstrations, military imposed curfews,10 strikes, and street marches. Life used to stop every day at 12:30 p.m., as there was a daily strike, which meant that all shops, schools, and universities would be closed at that time of the day. The rest of the day was the time for demonstrating against the Israeli military. There were whole months when schools were closed by the Israeli military, and we instead went to “home schools” in the neighborhoods organized by our community.

Though I cannot deny that as children we enjoyed the community aspect of this enforcement, the long hours for playing because of the closure of schools, and the excitement of sneaking out during the curfews to ask for food from the neighbors or simply to play in the neighborhood—“blessed” and “lucky” were not the words we would use to describe our reality. Almost every Palestinian of my generation could point to a traumatic moment or incident in which he or she was dehumanized or harmed by the armed Israeli soldiers and settlers, whether being (or witnessing a relative or a friend) beaten, humiliated, arrested, or, worst of all, shot. I still have clear and vivid m...