eBook - ePub

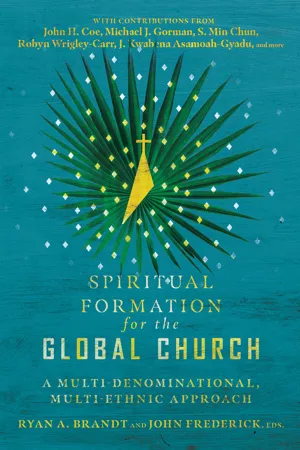

Spiritual Formation for the Global Church

A Multi-Denominational, Multi-Ethnic Approach

Ryan A. Brandt,John Frederick

This is a test

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Spiritual Formation for the Global Church

A Multi-Denominational, Multi-Ethnic Approach

Ryan A. Brandt,John Frederick

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The church is called to grow in Christ. Yet too often, it ignores the practical dimensions of the faith.The church is one in Christ. Yet too often, it is divided by national, denominational, theological, and racial or ethnic boundaries.The church is a global body of believers. Yet too often, it privileges a few voices and fails to recognize its own diversity.In response, this volume offers a multi-denominational, multi-ethnic vision in which biblical scholars, theologians, and practitioners from around the world join together to pursue a cohesive yet diverse theology and praxis of spiritual formation for the global church.Be fed in your faith by brothers and sisters from around the world.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Spiritual Formation for the Global Church an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Spiritual Formation for the Global Church by Ryan A. Brandt,John Frederick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Teologia ed etica sistematica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Teologia e religioneSubtopic

Teologia ed etica sistematica

CHAPTER ONE

NEW TESTAMENT THEOLOGY AND SPIRITUAL FORMATION

MICHAEL J. GORMAN

CHURCHES AND STUDENTS OF THE BIBLE—whether lay, clergy, or academics—in the West have often manifested certain perspectives with respect to the relationship between Scripture and spirituality. These include the following:1

Group 1

- 1. understanding both Bible reading and spirituality in individualistic and self-centered ways;

- 2. understanding spirituality in “otherworldly” ways;

- 3. creating a disjunction between spirituality, on the one hand, and mission and ethics, on the other;

Group 2

- 1. regarding academic biblical studies as superior to, and in conflict with, spirituality;

- 2. regarding serious study of the theology (or theologies) in the New Testament to be an appropriate academic discipline (sometimes called “New Testament theology”) but regarding study of that theology with a faith commitment, for theological and spiritual purposes (sometimes called “theological interpretation” and “spiritual reading”), to be inherently nonacademic and even nonintellectual;

- 3. regarding spirituality as superior to, and in conflict with, academic biblical studies, including the study of New Testament theology—either because academics is thought to be dangerous to one’s spiritual health or because Christianity is said to be about knowing a Person, not doctrine.

Space does not permit an elaboration of these various perspectives except to note that what they have in common is bifurcation: inappropriately separating that which (we might say) God has joined together. Each of them, I contend, misunderstands both Scripture and spirituality/spiritual formation. In my view, these sorts of bifurcated perspectives are misguided and, indeed, dangerous, both intellectually and spiritually.

The fundamental claim of this chapter is that New Testament theology is formational theology. The chapter will be devoted to looking at selected passages from the New Testament that demonstrate two things. First, we will briefly consider how the New Testament takes a “both-and” rather than an “either-or” approach to certain key topics hinted at in the list above. Second, and at greater length, we will see how the New Testament itself joins theology and spiritual formation. These two topics are, I believe, significant for spiritual formation both in churches of the West and in the global church.2 Furthermore, it may be necessary for the global church both to avoid the bifurcations noted above (often inherited from the West) and to assist churches in the West in recovering from these misunderstandings.

UNDERSTANDING THE NEW TESTAMENT’S “BOTH-AND” DYNAMIC

We can divide the six sorts of bifurcated approaches to reading Scripture noted above into two major categories: the vertical versus the horizontal (group 1: bifurcations 1–3),3 and the spiritual versus the intellectual (group 2: bifurcations 4–6). We may respond to each of these two major categories with two simple phrases: “God and neighbor” and “heart and mind.”

God and neighbor. We begin with the vertical versus horizontal bifurcations (1–3). The terms spirituality and spiritual formation are sometimes misunderstood to refer to a private experience of God that has no relationship to life in the real world and no necessary relationship to how we engage with others. What we find throughout the New Testament, however, is that our relationship with God is inseparable from our relationship with our neighbor. We find this inseparable connection expressed in various ways. A few samples will have to suffice.

- ♦ Like many ancient Jews, Jesus summarized the requirements of the Law and the Prophets as love of God and love of neighbor: “The first [commandment of all] is, ‘Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one; you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’ The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these” (Mk 12:29-31; cf. Mt 22:37-40; Lk 10:27-28).4

- ♦ “But when you thus sin against members of your family [lit. “your brothers”], and wound their conscience when it is weak, you sin against Christ.” (1 Cor 8:12)

- ♦ “When you come together, it is not really to eat the Lord’s supper. For when the time comes to eat, each of you goes ahead with your own supper, and one goes hungry and another becomes drunk. What! Do you not have homes to eat and drink in? Or do you show contempt for the church of God and humiliate those who have nothing?” (1 Cor 11:20-22)

- ♦ “For he is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us . . . for through him both of us have access in one Spirit to the Father.” (Eph 2:14, 18)

- ♦ “Religion [or “devotion”; CEB] that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world.” (Jas 1:27)

- ♦ “But no one can tame the tongue—a restless evil, full of deadly poison. With it we bless the Lord and Father, and with it we curse those who are made in the likeness of God. From the same mouth come blessing and cursing. My brothers and sisters, this ought not to be so.” (Jas 3:8-10)

- ♦ “We know love by this, that he laid down his life for us—and we ought to lay down our lives for one another. How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?” (1 Jn 3:16-17)

- ♦ “No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is perfected in us. . . . Those who say, ‘I love God,’ and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.” (1 Jn 4:12, 20)

All of these texts demonstrate that theology has consequences for how we treat our neighbor; that spirituality is about a relationship with both God and neighbor—simultaneously and inextricably. New Testament spirituality is personal, but it is not private.

What is fascinating about this brief selection of texts is how it shows the God-neighbor link in connection with various spiritual topics: love of God, relationship with Christ, experience of Christ in the Lord’s Supper, peace with God, devotion to God, blessing of God, experiencing love from God, and having God within. Many people would refer to these topics as in some sense “mystical.” Yet they are all also concerned about other people. There is no New Testament mysticism, or spirituality, without a connection to others; no vertical without the horizontal.5

Considering the goal of loving God and neighbor together, inseparably, leads us next to consider another inseparability in spiritual formation according to the New Testament: loving God with our minds as well as our hearts.

Heart and mind (and more). We turn next to bifurcations 4–6. It is sometimes thought that Christians do not need theology or rigorous, academic study of the Bible, since all that matters for spiritual growth in Bible reading is having a prayerful attitude, an openness to the Spirit. However, while prayerfulness and openness are always necessary for spiritual growth through Scripture study, they are not always sufficient.

A creative and helpful way to think about this matter was offered by N. T. Wright at the Synod of Roman Catholic bishops on the Word of God, which occurred in Rome in October 2008. Wright was, at the time, Bishop of Durham in the Church of England and an invited special guest at the Synod. Titled “The Fourfold Amor Dei [Love of God] and the Word of God,” Wright’s brief message drew on the words of Jesus (quoting the Shema; Deut 6:5) that we should love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength (Mk 12:29-30).6 Wright suggested that we think of engaging Scripture as employing—and balancing—these four aspects of our humanity.

We read with the heart, meaning meditatively and prayerfully, as in the medieval practice of lectio divina (“sacred reading”) that has enjoyed a transdenominational comeback in recent years.7 We read also with the soul, meaning in communion with the life and teaching of the church. We read as well with the mind, meaning through rigorous historical and intellectual work. And finally, said Wright, we read with our strength, meaning that we put our study into action through the church’s mission in service to the kingdom of God.

Wright’s words remind us that we cannot love God with only part of our being, which means that if we are reading Scripture to better know and love God, it will require the use of our minds. And that further means doing the hard work of rigorous study of the Scriptures. This does not imply that every Christian needs to be a trained New Testament scholar. But it does imply that carefully engaging New Testament theology to the best of our ability is an obligation—and a privilege!—given to all Christians. Loving God with our minds is one aspect of spiritual formation, and one way in which we are able to grow to maturity in Christ. Paul speaks of the need to “bring every thought into captivity and obedience to Christ” (2 Cor 10:5 NJB). This is doing theology, and when we read the New Testament with this approach (meaning with heart, soul, mind, and strength), we are both studying and doing New Testament theology. New Testament theology is inherently formational.

This last sentence contains a claim that requires a bit more unpacking.

One way of understanding the term theology is this: talk about God and all things in relation to God. Such a definition allows the possibility of a purely analytical approach to “doing theology,” including studying the theology we find in the New Testament. But the phrase “all things in relation to God” clearly invites us to do more than hold the contents of the New Testament at arms’ length. Another, ancient way of understanding theology is as “faith seeking understanding,” a phrase that comes from the great theologian Anselm (1033–1109). I would suggest, however, that Anselm’s definition needs expanding in light of Scripture’s own testimony about what it means to seek to understand God and all things in relation to God: “faith seeking understanding seeking discipleship.” That is, theology involves mind and heart and soul and body.

Theologians and other scholars often distinguish the study of New Testament theology from “theological interpretation.”8 The former is allegedly an academic pursuit that does not require a faith commitment, even if it permits one. The latter, on the other hand, exists only when such a commitment is present. My proposed reworking of Anselm’s definition of theology challenges this distinction. The New Testament is itself theology, a collection of early Christian theological writings whose focus is Christology and discipleship—and these two dimensions are inseparable. That is, the New Testament writings are meant to proclaim Christ and to form Christians, or what Martin Luther described as “Christs to one another” and C. S. Lewis called “little Christs.”9 The New Testament is theology seeking faith, so to speak; theology seeking spiritual formation in its hearers and readers. And because Christian spirituality must keep the vertical and the horizontal together, this spiritual formation will include formation in Christian ethics and mission.

Since spiritual formation is thei...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Spiritual Formation for the Global Church

APA 6 Citation

Brandt, R., & Frederick, J. (2021). Spiritual Formation for the Global Church ([edition unavailable]). InterVarsity Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2984506/spiritual-formation-for-the-global-church-a-multidenominational-multiethnic-approach-pdf (Original work published 2021)

Chicago Citation

Brandt, Ryan, and John Frederick. (2021) 2021. Spiritual Formation for the Global Church. [Edition unavailable]. InterVarsity Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/2984506/spiritual-formation-for-the-global-church-a-multidenominational-multiethnic-approach-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Brandt, R. and Frederick, J. (2021) Spiritual Formation for the Global Church. [edition unavailable]. InterVarsity Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2984506/spiritual-formation-for-the-global-church-a-multidenominational-multiethnic-approach-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Brandt, Ryan, and John Frederick. Spiritual Formation for the Global Church. [edition unavailable]. InterVarsity Press, 2021. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.