eBook - ePub

The Economics of Sustainable Food

Smart Policies for Health and the Planet

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Producing food industrially like we do today causes tremendous global economic losses in terms of malnutrition, diseases, and environmental degradation. But because the food industry does not bear those costs and the price tag for these losses does not show up at the grocery store, it is too often ignored by economists and policymakers.

The Economics of Sustainable Food details the true cost of food for people and the planet. It illustrates how to transform our broken system, alleviating its severe financial and human burden. The key is smart macroeconomic policy that moves us toward methods that protect the environment like regenerative land and sea farming, low-impact urban farming, and alternative protein farming, and toward healthy diets. The book's multidisciplinary team of authors lay out detailed fiscal and trade policies, as well as structural reforms, to achieve those goals.

Chapters discuss strategies to make food production sustainable, nutritious, and fair, ranging from taxes and spending to education, labor market, health care, and pension reforms, alongside regulation in cases where market incentives are unlikely to work or to work fast enough. The authors carefully consider the different needs of more and less advanced economies, balancing economic development and sustainability goals. Case studies showcase successful strategies from around the world, such as taxing foods with a high carbon footprint, financing ecosystems mapping and conservation to meet scientific targets for healthy biomes permanency, subsidizing sustainable land and sea farming, reforming health systems to move away from sick care to preventive, nutrition-based care, and providing schools with matching funds to purchase local organic produce.

In the years ahead, few issues will be more important for individual prosperity and the global economy than the way we produce our food and what food we eat. This roadmap for reform is an invaluable resource to help global policymakers improve countless lives.

The Economics of Sustainable Food details the true cost of food for people and the planet. It illustrates how to transform our broken system, alleviating its severe financial and human burden. The key is smart macroeconomic policy that moves us toward methods that protect the environment like regenerative land and sea farming, low-impact urban farming, and alternative protein farming, and toward healthy diets. The book's multidisciplinary team of authors lay out detailed fiscal and trade policies, as well as structural reforms, to achieve those goals.

Chapters discuss strategies to make food production sustainable, nutritious, and fair, ranging from taxes and spending to education, labor market, health care, and pension reforms, alongside regulation in cases where market incentives are unlikely to work or to work fast enough. The authors carefully consider the different needs of more and less advanced economies, balancing economic development and sustainability goals. Case studies showcase successful strategies from around the world, such as taxing foods with a high carbon footprint, financing ecosystems mapping and conservation to meet scientific targets for healthy biomes permanency, subsidizing sustainable land and sea farming, reforming health systems to move away from sick care to preventive, nutrition-based care, and providing schools with matching funds to purchase local organic produce.

In the years ahead, few issues will be more important for individual prosperity and the global economy than the way we produce our food and what food we eat. This roadmap for reform is an invaluable resource to help global policymakers improve countless lives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Economics of Sustainable Food by Nicoletta Batini in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Agribusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

We Depend on Food, Food Depends on Nature

Nicoletta Batini

“The truth is: the natural world is changing. And we are totally dependent on that world. It provides our food, water and air. It is the most precious thing we have and we need to defend it.” —David Attenborough

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in 2019, delegates spoke of a “Great Energy Transformation” needed to ensure a clean and secure energy future. No less urgent for the future of the planet is what we might call a “Great Food Transformation.”

While the climate implications of burning fossil fuels have received a great deal of attention, recent research by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows that what we eat, how we produce it, and how it gets to us exerts an even greater impact on the global environment and public health, a finding made even more evident by the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Greening food production and managing food demand to ensure that it is safe and nutritious for all are crucial for meeting the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the environmental pledge behind the UN’s Paris Agreement (Batini 2019b).

The True Cost of Our Food

Modern industrial agriculture has been described to the public as a technological miracle. Its advanced level of specialization and mechanization, we were told, would increase food production to meet the demand of a rapidly growing global population, and its economies of scale would ensure that farming remained profitable. But something crucial was left out of this story: the price tag.

Although productivity advances in agriculture have dramatically increased the supply of food, reducing the risk of global shortages, today hundreds of millions of people still go to bed hungry each night, and 2 billion more lack essential nutrients. Moreover, the way we produce food is making diets for the rest of humanity increasingly hypercaloric, undernutritious, and unhealthy, and unsafe food containing harmful bacteria, viruses, parasites, or chemical substances is a growing global threat leading to more than half a billion cases of illness a year (WHO 2020). Crucially, science shows that the practices currently used in conventional agriculture and fishing are harming the planet beyond repair (IPCC 2019; IPBES 2019; Willett et al. 2019).

Looking forward, fears are rising that industrial agriculture and fishing may not be able to feed a growing world because we are approaching the ceiling of what can be done to expand production industrially in terms of land, water, and chemical soil fertilization (FAO 2019). These challenges are aggravated by climate change, which is eroding the fertility of the land and the vitality of the sea, as well as making rain and other seasonal patterns more volatile and extreme (IPCC 2019). That should not surprise us: Since the inception of the not-so-green “Green Revolution”1 in the 1950s, agriculture has churned through natural resources, and we may soon reach the bottom of the bucket. As Schumacher (1973, p. 30) pointed out, “infinite growth in a finite environment is an obvious impossibility.”

Importantly, agriculture, fishing, and forestry are fundamentally different from other industrial sectors in that the former deal with living substances subject to their own laws, whereas the latter do not. Altering these laws, as through synthetic fertilization or genetic manipulation of factory-raised animals, is creating biological imbalances of vast proportions, the effects of which are known to be either extremely dangerous or totally unpredictable.

The crises of the modern food system—malnutrition, diseases, and ecosystem collapse—generate incommensurate economic costs. However, the importance of developing economic policies that can help transform the system have long disappeared from the economic profession’s radar screen because of the widespread belief that producing food industrially would solve global food problems. Reflecting this belief, economic analysis regularly disregards the primary sector and its interactions with the rest of the economy, and macroeconomic policy design largely abstracts from it on the grounds of the low value added and job intensity of the sector in the advanced world. Accordingly, when major developments wreak havoc on the food system, such as foodborne pandemics, mass extinctions, spikes in food prices, record crop losses, or record deforestation from abnormal wildfire seasons, they are treated as exogenous, unanticipated “shocks” even if they are the direct result of specific public or private agents’ actions.

The joint health and economic crises unleashed by the coronavirus outbreak and the burning down of large sections of the Amazon rainforest in 2019–2020 demonstrate that ignoring the role played by food systems in the economy is an expensive mistake not just from a public health and environmental perspective but also from an economic point of view. This is because food systems are an integral part of economic systems and intersect with human activity in many ways. Food systems do not only feed us, influence our health, and shape the way we interact with the natural world—including climate and pathogens. They also affect employment and labor productivity, drive international trade and domestic intermediate exchanges, and via land and sea rights have traditionally spurred exploration, commerce, and financial activities, helping to build nations’ wealth.

The industrialization of agriculture and fishing have not diminished the importance of food systems for people and economies but have distorted it, leading to five types of negative externalities:

- Environmental degradation. Scientific evidence from a variety of independent sources and fields unanimously identifies agriculture (crop and animal) as the single most important driver of climate change (IPCC 2019; Sanjo et al. 2016). Specifically, agriculture is estimated to be responsible for 21–37 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions because of the release of carbon dioxide from deforestation to claw back land for pasture and feedstock crops and from burning fossil fuels to power farm machinery and to transport, store, and cook foods; the release of methane from ruminant livestock; and the release of nitrous oxide from industrially tilled, heavily fertilized soils and liquid manure management systems (IPCC 2019). Beyond warming the atmosphere and catalyzing climate change, industrial agriculture is quickly exhausting other natural resources. It has led to the clearing of more than 40 percent of Earth’s arable land, a surface area equivalent to the size of South America, and global pastures currently occupy land equivalent to the surface area of Africa. In addition, irrigation for industrial agriculture is responsible for the biggest use of water on the planet, absorbing 70–80 percent of all available freshwater. Meanwhile, fertilizers have more than doubled the levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in Earth’s crust, leading to massive water degradation and pollution in the remaining water available for human consumption and other uses (Rockstrom et al. 2017). Likewise, commercial fishing is removing an increasingly large number of fish from the ocean, depleting key fish stocks, and many industrial fishing practices also destroy aquatic habitat, with far-reaching consequences for biodiversity, climate, and life on Earth more generally (WWF 2018).

These phenomena are bound to get worse. Hastened population growth and the shift to hypercaloric, animal-based diets, together with a ramp-up in the production of biofuels as fossil fuels run scarce, suggest that we will need to double global food production by 2050 and triple it over the following decades. Looking at livestock alone, for example, projections indicate that by 2050 animal production will increase by 80 percent compared with 2005 (Alexandratos and Bruinsma 2012), in line with estimates of the trend in the global demand for milk and meat (Fiala 2008; Thornton 2010). But these rhythms and methods of production are plainly incompatible with the sustainability of the world’s future food supply, heralding the advent of a simultaneous global agricultural, food, and water crisis.

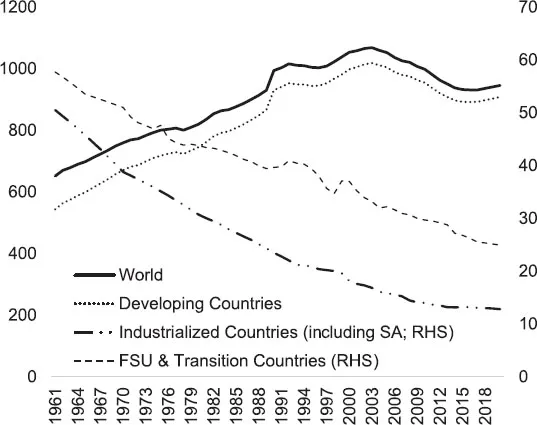

- Jobs and income inequality. Industrial agriculture also threatens jobs and income equality in a variety of ways. In advanced economies, as predicted by Colin Clark in 1951, the industrialization of agriculture has eliminated most agricultural jobs in the industrialized world (figure 1-1). Far more jobs have been lost in farming than in manufacturing over the past half century.

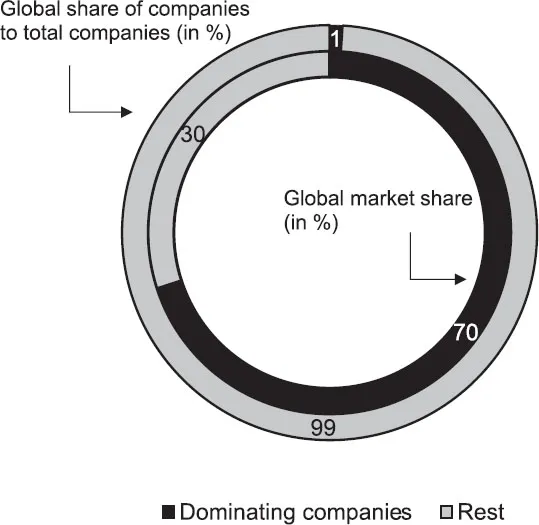

Although economy-wide unemployment did not materialize after the industrialization of agriculture, as new industries emerged and expanded, the transition between agricultural and manufacturing or service jobs had far-reaching impacts on income inequality both in rural and urban areas, with effects still vividly felt today (Judis 2016). Production is also massively concentrated vertically, with 1 percent of all companies dominating two thirds of world markets and even higher concentration in some domestic markets (figure 1-2). This has negative implications for price and wage setting and the types and quality of food and beverages produced.2

Figure 1-1. Agricultural labor by world region, 1961–2020 (in millions of persons active, 15+ years, male and female). Sources: ILO Model estimates, May 2018 update; USDA Economic Research Service.

In emerging and developing economies, agricultural industrialization is significantly less advanced, and agriculture in these economies still employs about 1 billion people (ILO 2019). However, if agriculture were to follow the same destiny observed in advanced economies and to be industrialized as implied by UN projections on urbanization trends (UN 2018), most of these jobs could be permanently lost, leading to a quadrupling of 2019 global unemployment. Industrial agriculture in the advanced world, on the other hand, is already a leading cause of income inequality and poverty in developing countries: Subsidies to industrial agriculture in advanced economies distort international commodity prices, making it cheaper for developing countries to import rather than continue to produce food. This not only destroys the main source of income in subsistence economies; it also makes countries dependent on imports for food (among many others, see Alam et al. 2015; Boltvinik and Mann 2016).3 The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to affect food prices internationally and plunge developing economies into deeper debt (FAO 2020; UNSCN 2020).

Figure 1-2. Global food industry market concentration. Sources: Dow Jones Factiva; Oxfam International (2013).

- Malnutrition and food insecurity. At the end of the eighteenth century, Malthus postulated that agricultural innovations would raise prosperity only fleetingly: By stimulating population growth, more food would lead to a fight for scarce resources, causing hunger, war, and diseases. In turn this would restrain economic growth and put a lid on population growth. Malthus’s prediction has long been dismissed as spectacularly wrong, because continuous advances in food production—alongside medical advances and improvements in sanitary infrastructure—have ensured a permanent global food glut and continual growth in global longevity. But although Malthus was wrong yesterday, he probably would have been right today and tomorrow in two important respects. First, although industrial agriculture has ensured that increasing amounts of food are produced globally, this has not solved world hunger. Major distributional problems remain between and within nations, with about 2 billion people around the world overeating and 3 billion undereating. Furthermore, a third of all food produced is wasted. The misallocation of food, in turn, is a cause of persistent differentials in the levels of prosperity around the world, and thus of migration and conflicts. Second, the ecological footprint from current agricultural methods demonstrably exceeds the carrying capacity of the planet. Absent bold and globalized policy action, this is bound to hamper production soon, causing either a massive rationing of food or drastic adjustments in food prices, making food unaffordable for billions of people. To make things worse, as the current COVID-19 crisis has shown, the global food supply chain—heavily concentrated, globalized, and operating on a just-intime supply basis—is likely to falter and fail in the case of major events such as natural disasters or pandemics, a high-probability scenario in a world of swift climate change (Batini et al. 2020; see also Blay-Palmer et al. 2020). In some cases, we do not have the ability to produce food. In other cases, we can produce it but do not have the ability to process it and package it, a limitation conducive to industrial-scale food crises. This is aggravated by the fact that large swathes of the food system rely on foreign seasonal labor, which depends on migration flows, which in turn are volatile and hinge on the resilience of international travel—gravely disrupted during the pandemic, for example—and migration policies.

- Rural exodus and urbanization. The industrialization of food production has contributed to a global phenomenon of rural-to-urban migration. It is estimated that the rural population represented almost two thirds of the total population of the world in the middle of the twentieth century. Since then, the percentage of people living in rural areas has been decreasing at a very fast rate. The rate of decrease remained roughly the same between 1950 and 2000, at around 2 percent every 5 years, or 0.35 percent per annum. The projections suggest that this phenomenon will accelerate in the future: In 2030, only 40 percent of the world population will live in rural settlements, reflecting a rapid rate of decrease of 0.44 percent per year projected from 2000 to 2030 (UN 2018). Different continents have different patterns of urbanization, but the consequences in the rural population are similar. They include the disappearance of rural cultures, the increased risk of economic instability and deviant behavior among rural–urban migrants, higher unemployment in urban areas, changes in fertility behavior, and cultural tensions in urban areas. Crucially, the decline in agricultural employment has led to a degradation of human skills in traditional agriculture, which may aggravate the shift to industrial agriculture. Urbanization also adds to environmental degradation on two levels. First, poor air and water quality, insufficient water availability, waste disposal problems, and high energy consumption are exacerbated by the increasing population density and demands of urb...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface — Nicoletta Batini

- 1. We Depend on Food, Food Depends on Nature — Nicoletta Batini

- I. Greening Food Supply

- II. Greening Food Demand

- III. Greening Food Waste

- IV. Conserving Land and Sea to Support Food Security

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Index