eBook - ePub

A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation

Uniting Design, Economics, and Policy

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation

Uniting Design, Economics, and Policy

About this book

Tens of millions of Americans are at risk from sea level rise, increased tidal flooding, and intensifying storms. The design and policy decisions that have shaped coastal areas are in desperate need of updates to help communities better adapt to a changing climate. A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation identifies a bold new research and policy agenda and provides implementable options for coastal communities.

In this book, coastal adaptation experts discuss the interrelated challenges facing communities experiencing sea level rise and increasing storm impacts. These issues extend far beyond land use planning into housing policy, financing for public infrastructure, insurance, fostering healthier coastal ecosystems, and more. Deftly addressing far-reaching problems from cleaning up contaminated, abandoned sites, to changes in drinking water composition, chapters give a clear-eyed view of how we might yet chart a course for thriving coastal communities. They offer a range of climate adaptation policies that could protect coastal communities against increasing risk, while preserving the economic value of these locations, their natural environments, and their community and cultural values. Lessons are drawn from coastal communities around the United States to present equitable solutions. The book provides tools for evaluating necessary tradeoffs to think more comprehensively about the future of our coastal communities.

Coastal adaptation will not be easy, but planning for it is critical to the survival of many communities. A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation will inspire innovative and cross-disciplinary thinking about coastal policy at the state and local level while providing actionable, realistic policy and planning options for adaptation professionals and policymakers.

In this book, coastal adaptation experts discuss the interrelated challenges facing communities experiencing sea level rise and increasing storm impacts. These issues extend far beyond land use planning into housing policy, financing for public infrastructure, insurance, fostering healthier coastal ecosystems, and more. Deftly addressing far-reaching problems from cleaning up contaminated, abandoned sites, to changes in drinking water composition, chapters give a clear-eyed view of how we might yet chart a course for thriving coastal communities. They offer a range of climate adaptation policies that could protect coastal communities against increasing risk, while preserving the economic value of these locations, their natural environments, and their community and cultural values. Lessons are drawn from coastal communities around the United States to present equitable solutions. The book provides tools for evaluating necessary tradeoffs to think more comprehensively about the future of our coastal communities.

Coastal adaptation will not be easy, but planning for it is critical to the survival of many communities. A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation will inspire innovative and cross-disciplinary thinking about coastal policy at the state and local level while providing actionable, realistic policy and planning options for adaptation professionals and policymakers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation by Carolyn Kousky, Billy Fleming, Alan M. Berger, Carolyn Kousky,Billy Fleming,Alan M. Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Designing for Equitable Resilience

CHAPTER 1

A Comprehensive Framework for Coastal Flood-Risk Reduction: Charting a Course Toward Resiliency

Samuel Brody, Kayode Atoba, Wesley Highfield, Antonia Sebastian, Russell Blessing, William Mobley, and Laura Stearns

COASTAL FLOODS ARE NOW THE COSTLIEST and most disruptive natural hazard worldwide. Increasing physical risk combined with rapid land use change and development in flood-prone areas is amplifying adverse economic and human impacts. Never before have the repercussions from storm events driven by both surge and rainfall been so damaging to coastal communities. Cumulative losses from chronic floods, punctuated by acute events, such as Hurricane Harvey in 2017, have become especially problematic in the United States, where development in increasingly vulnerable coastal areas has accelerated over the last several decades.

Current US flood policy focuses primarily on recovery mechanisms, such as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and other types of federal financial assistance that enable communities to rebuild after a flood disaster. Even flood-mitigation techniques that take a more proactive approach to reducing risk are often implemented in a haphazard manner post-flood across various scales and organizations. Furthermore, ad hoc strategies implemented as a reaction to specific storm events have resulted in a muddled patchwork of flood defenses and development policies that ignore the broader systemic nature of flood risk nationwide and can sometimes lead to inequitable allocation of resources to local communities.

A Framework for Coastal Flood-Risk Reduction

To more effectively address the growing threat of floods in coastal areas, communities will need to consider and adopt a range of different mitigation strategies working synergistically over time. These activities range from updating drainage infrastructure and elevating structures to protecting naturally occurring wetlands and improving techniques for risk communication. While the specific portfolio of flood-risk reduction strategies will depend on the unique characteristics of each local jurisdiction, it must draw from a common set of approaches.

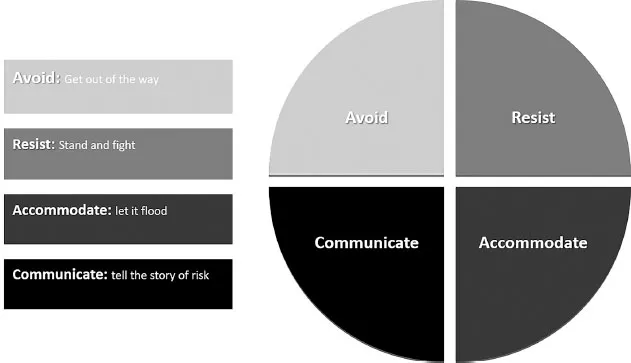

This chapter presents an integrated framework for coastal communities interested in reducing flood risk and associated impacts over the long term. The framework comprises four mitigation categories that every flood-prone community should consider: Resistance, Avoidance, Accommodation, and Communication (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Flood-Risk Reduction Framework. Adapted from Eye of the Storm, 2018.

This framework is based on initial concepts presented in the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas (CRT) Eye of the Storm report written in response to Hurricane Harvey in 2017.1 Within each category, we describe the major structural or nonstructural mitigation techniques available to coastal decision makers at the local jurisdictional level (table 1.1). Specifically, we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of pursuing a specific strategy, under which conditions it might be most appropriate, and how various strategies may be combined to produce positive synergistic effects. While impetus and resources for policy change may originate at the federal level, these new strategies must ultimately be implemented at the local level.

Resistance

A major component of flood protection in the United States is to resist the intrusion of wave- or rainfall-based floodwater into human settlements. Resistance strategies most often involve structural measures such as large-scale building and construction projects, including levees, seawalls, and dams, that actively protect communities situated in vulnerable areas. This “stand and fight” approach to flood-risk reduction recognizes the importance of protecting development in flood-prone areas for commerce, industrial production, recreation, and aesthetics.

ARMORING

A major aspect of structurally based resistance activities involves “armoring” the coastline. Typically, coastal armoring is considered a last resort due to its adverse environmental impacts and used where substantial human investments are at risk, making it necessary to protect the upper portion of a beach profile from storm-induced erosion and flooding.2 One of the most popular options is the construction of dikes or levees that restrict rising waters in the “channel phase” of flooding.3 These structures often consist of solid concrete walls, either above or below ground, that prevent elevated water levels from flooding interior lowlands. Dikes are usually associated with eliminating wave-based flooding caused by storm surges along the coast. Levees are located along stream and river channels to prevent flooding from rainfall runoff or storm surge that travels upstream along the floodplain. These structures are best used where there is existing development or critical facilities, such as oil and gas production or power plants. These structures are often expensive and politically contentious and can have adverse environmental impacts, making them ill suited for use everywhere. In addition, if used unwisely, such structures could become perverse incentives and encourage development in floodplains, actually further increasing values at risk. Moreover, if they are not monitored and maintained properly, the risk of failure increases, causing catastrophic damage.

The construction of movable floodgates or storm barriers is increasingly being used as a resistance strategy to prevent widespread inundation of coastal communities. These structures consist of adjustable gates designed to prevent a storm surge or high tide from flooding the protected area behind the barrier. A surge barrier is usually integrated into a larger flood-protection system consisting of floodwalls, levees/dikes, and other mitigation strategies. Modern-day barriers situated at the mouths of estuaries or river outflows allow water to pass under natural conditions until the structure is closed due to an impending storm. Storm surge barriers and floodgates are most notable in the Netherlands but have also been implemented in St. Petersburg, Russia; England; New Orleans, Louisiana; and, most recently, Venice, Italy.4 Many of these structures are praised for their ability to eliminate the threat of storm surge–based flooding without significant environmental impacts, but they can be difficult to implement due to the large amount of time, expense, and engineering capabilities required. Additionally, local support for expensive coastal structures will likely appeal to wealthier communities in surge-prone areas, while less affluent communities would prioritize allocating federal and local funds to other pressing needs.

Revetments consist of erosion-resistant materials placed on an existing slope, embankment, or seawall to protect the backside area from storm-driven waves. Different types of materials are used to absorb wave action, including geotextiles, sandbags, concrete tetrapods, rock, or wood.5 Revetments are generally low-cost coastal flood-mitigation techniques that complement other structural approaches. For example, earthen dikes with stone revetments have been constructed to protect major petrochemical facilities in Texas City, Texas, from the adverse effects of coastal storms and high tides. While revetments are ubiquitous for coastal mitigation across the United States, they are also prone to failure. If the toe fails, the entire revetment can unravel. Also, overtopping and loss of foundation material can negate the effectiveness of this armoring approach.

Table 1.1 Flood-Risk Reduction Strategies

| Mitigation Strategy | Description |

| | Resistance |

| Dikes/Levees | Solid constructed walls that prevent elevated water levels from flooding interior lowlands. |

| Dams | Artificial barrier usually constructed across a stream channel to impound or store water. |

| Floodgates/Barriers | Adjustable gates that prevent storm surge from flooding coastal areas. |

| Breakwaters | Detached structures built parallel to the coast. |

| Groins/Jetties | Typically short structures attached perpendicular to the shoreline, extending across at least part of the beach out into the surf zone. |

| Bulkheads | Vertical retaining walls to hold or prevent soil from sliding seaward. |

| Revetments | Armoring materials placed on an existing slope, embankment or seawall to protect the backside area from storm-driven waves. |

| Artificial Reefs | Construction of reefs in nearshore areas to reduce the impacts of storm surge and waves. |

| Constructed Dunes | Building or replacing dunes to protect communities from storm surge and wave action. |

| | Avoidance |

| Freeboard/Building Elevation | Elevating structures above base flood to protect from inundation. |

| Fill | Elevating landscapes with compacted soil or dirt before construction of buildings to prevent inundation. |

| Buffers/Setbacks | A specific distance for which structures must be set back. |

| Clustering | Increasing the permissible development density in the least vulnerable areas within a specific property. |

| Density Bonuses | Increasing development density and height requirements for specified parcels. |

| TDRs | Transfer of development rights from a vulnerable area to a less vulnerable or sensitive area. |

| Targeted Public Infrastructure | Invest in public utilities and other infrastructure in the least vulnerable areas. |

| Acquisition | Purchase of some or all property rights for open space protection for flood mitigation. |

| Relocation | Remove structures from a vulnerable location to a less vulnerable location. |

| Drainage Maintenance | Maintaining drainage devices (canals, ditches, storm drains, etc.) to ensure they operate effectively during a flood event. |

| Protected Areas/Open Space | Designating one or multiple parcels as protected open space for flood mitigation. |

| Local Plans | Adoption of local planning instruments (e.g., floodplain plans, comprehensive plans, local mitigation strategies, etc.) that set forth a series of coordination policies aimed at mitigating flood impacts. |

| Low Impact Development | Development standards and techniques designed to work with ecological functions to manage stormwater as close to its source as possible (e.g., bioswales, rain gardens, permeable pavement). |

| | Accommodation |

| Retention/Detention | Either dry or wet holding areas/ponds that collect stormwater. |

| Underground Cisterns | Large stormwater holding areas underground. |

| Breakaway Walls | First-story walls on elevated homes designed to break away during storm surges. |

| Garage Vents | Openings at the base of a garage that allow water to pass through the structure. |

| Protected Open Space | Designating protected open spaces or passive recreation sites for flood detention. |

| Constructed Wetlands | Creating wetlands around structures or on vacant parcels. |

| | Communication |

| Flood-Risk Information | Providing information about flood risks through multiple media outlets. |

| Education/Training | Training through classes, workshops, certifications, etc. |

| Hazard Disclosure | Disclosing a property’s potential flood hazard to prospective buyers before the lender notifies them of the need for flood insurance. |

MODERATING

A second set of structural flood-resistance activities involves “moderating” the impacts of coastal storms. Beach erosion control techniques are one such set of moderating resistance measures designed to reduce the rate of sediment loss and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword—Jeff Goodell

- Introduction: The Changing Risks of Coastal Communities—Carolyn Kousky, Billy Fleming, and Alan M. Berger

- Part I: Designing for Equitable Resilience

- Part II: Adapting Public Policy and Finance

- Contributors

- Index