![]()

PART ONE

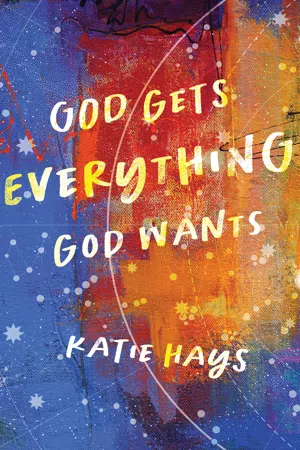

GOD GETS EVERYTHING GOD WANTS

![]()

1

ONLY TWO STORIES (OK, ONLY ONE)

What if, instead of a Babel tower of symmetric, stacking blocks, we pictured faith like a pattern of concentric circles? Like a dartboard, or—better, for the absence of sharp, spiky projectiles—like the ripples that disturb the water around a pebble you just plunked into a pond? In the middle of all the rings, a hot, molten core like the center of the earth, glowing and gorgeous. In the middle of me, the glowing golden nuggets I dug from the rubble of my faith and swallowed. (Mixing metaphors, I know. But I trust you, dear reader, to be nimble and forgiving.) Moving out from the center, rings that are further and further away are less and less connected to that core.

Then, concerning what we believe or trust or fear or hope with respect to God, the universe, and everything, we could locate a very small set of Very Important Things in the hot, molten core. Moving out from the core, there would be possibilities for faith, things to believe in or not. But the further away from the center you got, the less likely you’d be to, you know, argue the point.

I happen to think when people come to Galileo Church they deserve to know what’s in my hot, molten core. Like, what do I believe so hard that I believe it in my bones? Having confessed that I believe a lot less than I used to (I mean, quantitatively fewer pieces of Christian doctrine than I used to), having told you that my own tower of faith collapsed a long time ago, you should be asking me, as I would ask you: What is left? What invaluable pieces were exposed when the tower toppled, that you excavated and hung on to? What is the content of this gospel you keep preaching, anyway?

Thanks for asking!

To move toward my answer to that question, we have to take another look at The Greatest Story Ever Told—aka the Bible.

God versus Pretenders: God Wins! (Part One)

What if I told you there’s really only one narrative in the whole Bible? Only one main character, only one main plotline? And every story our ancestors told, every commandment they chiseled into stone or had written on their hearts, every mile that Jesus and his followers trudged through Galilee and Jerusalem and to the ends of the earth, every bit of it was in support of one grand thesis? One Big Idea?

The main character, the Protagonist, is God. The plotline is, God wins. The thesis, the One Big Idea, is God Gets Everything God Wants.

Let me show you what I mean.

The story begins, as all good stories do, “Once upon a time.” Or, “In the beginning”—same difference. And there follows, in Genesis, the establishment of setting (“the heavens and the earth”) and the introduction of our Protagonist (God), along with a cast of supporting characters (all of us, all of creation). Rather quickly in the telling, it’s established that the character called God is in charge of the whole enchilada—God made it, God set it in motion, God knows how it’s all supposed to work, and God thinks it’s terrific.

But it’s also the case, from very early in the story, that God’s in-chargeness is disputed. The world might indeed belong to God and sing God’s name, but God is not the kind of god who micromanages, so there are all kinds of chances for things to go wrong—i.e., against the grain of what God wants for and from God’s world. We’ll come back to that later.

For now, we can jump ahead just a little ways, to Exodus, and find God in a good ol’-fashioned turf war with a powerful antagonist called Pharaoh. Pharaoh pretty much believes that the world is his hamburger, as all empire builders are inclined to believe; and so he believes he can take whatever he wants from it, including a labor force of enslaved people to build all his cool stuff. To mark his territory, as it were.

But our guy God, as it turns out, has a keen ear for suffering (Exod. 2:23–25). The enslaved people groan because of all they’ve endured for so long (because some pain is only expressible in proto-linguistic sounds; because that’s how chronic, generational trauma and suffering changes people; and because they’ve long since forgotten that their ancestors were tight with the God of the cosmos). And God goes, “Hey, this is not how my world is supposed to work!” And God gets busy on a plan to liberate the enslaved people from Pharaoh—not just Pharaoh the man but Pharaoh the system, Pharaoh the mindset, the way things work when Pharaoh is in charge.

God throws down to Pharaoh: “Let my people go.” And Pharaoh’s like, “Nuh-uh, those are my people. You can’t have ’em.” And now they’re wrestling, and Pharaoh’s losing, and the way this story goes, God will stop at nothing to show Pharaoh who’s the boss. God is willing to work it out so that nobody gets hurt, but Pharaoh’s not, and if violence is the only rule Pharaoh respects, it’s completely within God’s power to be violent in order to establish that the stuff God has made, including people, can’t be dominated by any pretenders to the cosmic throne.

End result: God gets what God wants. The liberated people now known as “the people of God,” or “God’s people,” spend the rest of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy getting used to a world where God is in charge. They have things to learn, such as:

> how to rest every seventh day, trusting that they don’t have to work and worry 100 percent of the time. In God’s economy (distinct from Pharaoh’s economy) rest is built into the calendar (for all humans, work animals, and even the dirt) to reinforce the memory that everything they have comes from God anyway, by the power of God’s own intervention and gift, not by the sweat of their own brow, as before.

> how to open their clenched fists and let go, giving up some of their best stuff to God and to each other, in trust that God’s provision is abundant and they can therefore afford to be generous.

> how to govern themselves cooperatively, with rules that protect the vulnerable and restrain the powerful, drawing individual persons into a collective identity as a people.

> how to trust that what God wants is ultimately good for them, even when they don’t have a road map for their journey and can’t see very far ahead and thus can’t pretend to control their own destiny.

Letting God be God is really hard, as it turns out, and requires a lot of very specific instructions and tons of practice, including any number of mistakes. But all those instructions, all that practice, and all those mistakes are in support of the One Big Idea in the Bible: God gets everything God wants.

The careful reader will notice that the Hebrew Bible basically recapitulates this whole story—the liberation of the small, disempowered Israelite tribes and their subsequent formation into a people made strong by being in covenant with the God of the universe—over and over and over again. Sometimes it’s really obvious, like in Deuteronomy 6:20–25, where the Israelites are asked to tell the story of their ancestors’ liberation from Egypt forever, to their kids and their kids’ kids and so on. Or like in Ezra 6:19–22, where after a jillion generations and lots of geopolitical drama the remnant of Israelites returning again to their beloved Jerusalem reintroduces the annual celebration of Passover to commemorate God’s sound defeat of Pharaoh many hundreds of years ago as if it just happened.

Sometimes the recapitulation of Exodus is more subtle, as when biblical prophets and poets name God the “Redeemer,” because “redeeming” is the action word for rescuing someone from enslavement or captivity. Or they’ll go completely metaphorical, drawing attention to God’s “mighty hand and outstretched arm,” the body parts by which God was said to have bested Pharaoh (Deut. 4:34, 2 Chron. 6:32, Ps. 89:13, Jer. 21:5 … we could go on and on).

The point is: no matter what part of the Hebrew Bible you’re reading, you’re basically reading the story of Exodus again and again. God takes on a pretender to God’s throne; God rescues a small, oppressed people; God forms the liberated little ones into God’s people; God promises to love and take care of them forever; God’s feelings get super hurt when they reject God’s forever love and care. “The Exodus is how we know who God is,” the Hebrew Bible says. “The Exodus is how we know who God will always be.”

God versus Pretenders: God Wins! (Part Two)

“OK,” you might be saying now. “OK, I checked it out and there is sure ’nuff a lot of Exodus in the Hebrew Bible. Makes sense. But what about the New Testament? That’s not about Exodus. That’s about Jesus, obviously. Right?”

Exactly right: the Christian scriptures introduce us to Jesus—who, by the way, himself celebrated Passover, as one of the descendants of those faithful Israelites who told the Exodus story again and again and again. And in a while I’ll have lots more to say about Jesus’s ministry as reported in the Gospels. But for this moment, let’s stay with the One Big Idea: that God gets everything God wants, even when it means doing combat with pretenders to God’s throne.

Jesus of Nazareth was born in the region of Galilee, one of thousands of provinces that the Roman Empire had swallowed up in its attempt to rule the world. His entire life was lived under occupation by an army under Caesar’s command, an army with orders to enforce Caesar’s ownership and bankroll Caesar’s expansion by oppressive taxation that kept people working relentlessly. It wasn’t Pharaoh’s enslavement, exactly, but it was close.

And it was Roman imperial law that could not tolerate anyone who threatened or subverted Caesar’s authority. It was under Roman imperial law that anyone who competed with Caesar for the loyalty of his subjects could be executed. It was the Roman imperial judicial system, represented in a sham trial with perjured witnesses (Mark 15:3–4), that found Jesus guilty, sentenced him to death, and executed him. Yep, there was an entanglement there with religious authorities who themselves felt threatened by stuff Jesus said and did, but it was a Roman imperial court that decided his fate and a Roman imperial military police force that carried out his sentence.

When his followers told the story later they would insist that the Roman Empire and its Caesar were too puny to be named as the perpetrators of Jesus’s death. They would say it was Death Itself what done it—that the Enemy Death carried Jesus into captivity, intending to permanently enslave him in nonexistence (Acts 2:24, Rom. 6:9). The Romans simply acted as Death’s unwitting proxy. At the most basic level, one way to say why Jesus had to die is that everybody dies—because Death has a hold on humanity, like a Pharaoh or a Caesar, pretending that it can do what it wants, take what it wants, because it can’t be beat.

But listen, don’t ever tell God that you can’t be beat. Don’t ever pretend that the world is your hamburger. Because God will take that challenge, and God will whoop your ass. Pharaoh, Caesar, even Death itself, and the systems that afford them their illegitimate power—God goes up against all of them and God declares victory. That’s how this story always goes, according to the Bible.

Like, in the case of Jesus and his captivity to Death, his lifeless body lying in a cold tomb over the weekend, waiting for someone to take care of it—God takes one look at that, and God says, “Nope.” And God calf-ropes Death. Just in case you’re not from Texas: God (on horseback, of course) lassos Death around the neck, jumps down from the horse, flips Death over on its back, ties three of Death’s legs together, and won’t let go until Death surrenders and gives back what Death stole from God. And that, guys and gals and nonbinary pals, is what we call resurrection.

And it can be argued—I’m arguing!—that the Christian scriptures recapitulate the resurrection of Jesus over and over and over again. Even before his death, whenever Jesus walks on water or multiplies food or heals sick bodies or restores family relationships, the Gospels foreshadow his resurrection, hinting broadly that he simply isn’t bound by the laws of the natural universe the way the r...