This chapter first discusses the evolution of the political and policy context from the 1970s to the late 1990s, to put in perspective the progress of implementation of the major ocean and coastal programs enacted in the 1970s. It then examines, in closer detail, the evolution of policy in each of several sectors: coastal management, fisheries management, marine mammal protection, offshore oil and gas development, marine pollution control, and marine protected area management.

The Political and Policy Context of the Period

A flurry of activities on the part of federal agencies charged with implementing the new ocean and coastal acts ensued, as agencies worked to interpret the far-reaching statutes enacted in the 1970s, to put in place new decision processes, and to mobilize new resources. Many federal agencies were ill prepared to implement some of the innovative concepts contained in the new acts. Amidst these developments, the energy crisis of 1973—1974 torqued national ocean policy, for a time, toward the goal of energy independence, inducing, in the process, extensive conflicts between energy developers and the environmental interests that had been spawned earlier in the decade. Other conflicts took place as well, as various interest groups found themselves affected by the legislative actions made in other sectors. Litigation began to increase and escalated in the 1980s, particularly around offshore oil issues and fisheries /marine mammals conflicts.

In the 1970s, a clear move toward federal dominance in ocean policy matters had taken place, but in the 1980s, the pendulum swung more toward the states, in rhetoric, at least. The Reagan administration (1981—1989) brought with it a philosophy that the federal government was too big and that there was too much regulation of economic development activities, especially too much environmental regulation. The solution to this fundamental problem, in President Reagan’s view, required a drastic shrinking of governmental programs, activities, and regulations. The administration called for a “New Federalism,” which shifted government functions to state and local levels (often, however, without corresponding funding).

Many of the programs authorized in the 1970s were targeted for spending reduction, and some (such as coastal zone management and sea grants) were targeted for outright elimination. While these efforts were largely rebuffed through concerted action by Congress, the coastal states, and environmental organizations, the 1980s saw little growth in federal ocean programs, with the exception of a few legislative initiatives: the 1987 National Estuary Program (section 320 of the Clean Water Act),1 the 1982 Coastal Barrier Resources Act (16 U.S.C. , 3501 et seq.),2 the 1972 Ocean Dumping Act (Titles I and II of the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, as amended, 33 U.S.C.,1401 et seq.),3 and the 1990 Oil Pollution Act (33 U.S.C., 2701 et seq., inter alia).4 This period was typified by increasing conflicts, particularly with regard to offshore oil, with environmental interest groups ultimately successful in achieving a series of congressionally mandated moratoria on spending for offshore oil leasing activities.

Almost in reaction to the downturn in federal interest in the oceans, the late 1980s and the 1990s witnessed increased activism on the part of the coastal states and coastal communities, with, for example, a number of coastal states preparing integrated plans for the management of their offshore areas, with some of these (such as Oregon) going beyond the legal bounds (3 miles) of state jurisdiction (Bailey 1994). A great deal of experimentation on ocean, coastal, and estuarine management took place during this period, especially at the local level, with increased participation by a variety of stakeholders (private sector, environmental interests, state and local governments) in decisions about coastal and ocean resources. This period was also marked by the emergence of new management concepts (such as watershed management and ecosystem management) that emphasize the need to manage on the basis of natural systems rather than political jurisdictions (see, e.g., Imperial and Hennessey 1996).

The 1990s also witnessed profound changes in international relations as well as major changes in ocean and coastal management at the international level. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the growth in regional economic blocks (Europe, North America, East Asia), the globalization of economic activities, the growth in tensions between the North (developed countries) and the South (developing countries) over issues related to environment and development, and the growing role of international trade agreements were all major factors that shaped foreign, and to a lesser extent domestic, policy in the 1990s. In the oceans arena, a major change to the Law of the Sea Convention, in the form of a new agreement revising the deep-seabed mining regime, made the LOS acceptable to major industrialized nations, such as the United States, which, in 1994, indicated its intention to seek Senate ratification of the treaty. The LOS treaty came into force in November 1994 following ratification by the sixtieth nation. In addition, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (the Earth Summit) in June 1992 brought major new paradigms to the fore—the concept of sustainable development, and major changes in ocean and coastal management thinking and practice through Chapter 17 (the oceans and coasts chapter) of Agenda 21 (the global blueprint on environment and development), and through the conventions on biological diversity and on climate change (Cicin-Sain and Knecht 1993).

Major new international accords were also made to halt the worldwide degradation of fisheries, such as the adoption of the 1994 agreement on straddling fisheries stocks and the FAO code of conduct for responsible fisheries. The United States participated in all of these international discussions, albeit sometimes reluctantly. While these advances in thinking at the international level had, in many cases, far-reaching impacts on the national behavior of other nations, by the end of the 1990s, they generally appeared to have little impact on U.S. domestic policy on oceans and coasts.

At the end of the 1990s, there is a growing consensus about the problems besetting single-sector management of the oceans, and the need to develop more integrated management approaches (Heinz Center 1998). Initiatives to create a national commission to provide a comprehensive examination of ocean policy and to create a national ocean council have become major factors in the discussion of future policy directions (Knecht, Cicin-Sain, and Foster 1998).

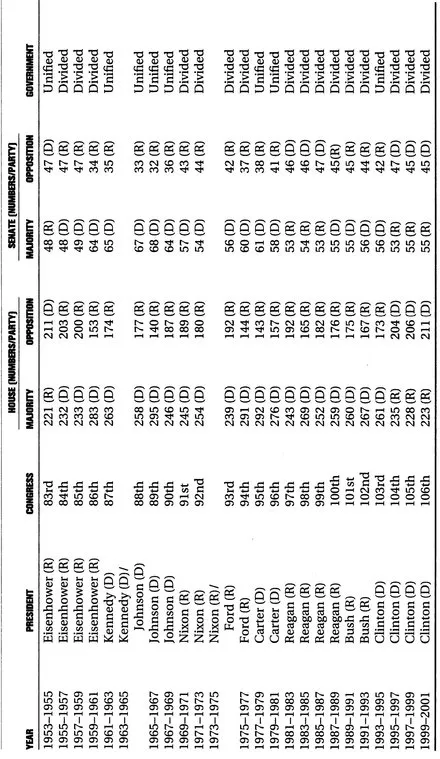

Politically, much of this period has been characterized by “divided” government, that is, one party holding the presidency while the other holds the congressional majority in one or both houses of Congress. In fact, as Table 4.1 suggests, in the period 1969 to 2000, the government was divided fourteen out of sixteen times. A situation of divided government, of course, makes the formulation and implementation of any policy more difficult, and requires that bipartisan support must be garnered in order for policy proposals to be successfully enacted and implemented. Bitter partisanship between the president and the Congress was especially pronounced during the 104th Congress (1995—1997), which was marked by Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America” and the accession of Republicans to the majority in both houses of Congress. Such partisanship continued in the 105th Congress, culminating in the impeachment of President Clinton in the House in December 1998.5

TABLE 4.1 Incidence of “Divided” or “Unified” National Govemment, 1953-2001.

Source: Adapted from Ragsdale 1996

During this period, the ocean policy landscape has changed from the domination of isolated “iron triangles,” which predominated in the early 1970s, to the emergence of much more interaction among interests representing various ocean sectors—“issue networks” as Heclo (1978) calls them. This is especially true in the case of groups representing fishers and marine mammal protection who have been forced to deal with each other in resolving conflicts between marine mammals and fisheries. There have been efforts throughout this period to bring together environmental interests and offshore oil and gas interests, but relations among these groups remained largely wary and acrimonious at the end of the 1990s. Some programs, such as the National Estuary Program, have achieved some notable successes in bringing together a variety of stakeholders (representing all coastal sectors and government jurisdictions) in efforts to manage particular bodies of water; but all too often, the lack of implementation follow-through has blunted the effectiveness of these efforts. And although there has been growing admission among all ocean and coastal interests that more integrated management is needed, a powerful political coalition pushing for this perspective has yet to appear.

The 1973—1974 Energy Crisis and Its Impacts

Just as ocean programs enacted in the 1970s were coming on line, the energy crisis developed and legislative actions were taken to address it. The Arab oil embargoes of 1973—1974 took most Americans by surprise. Gasoline to power America’s automobiles and oil to generate electricity have been viewed as essential to the modern American way of life and were very much taken for granted. Thus, the disrupted oil supplies focused public attention in a way that more diffuse environmental problems or the crisis of confidence in our educational system (during the Sputnik crisis) could not.

A number of the ocean and coastal laws enacted in the early 1970s, however, were not seen as helpful to the perceived energy problems. Laws to protect marine mammals and endangered species, to the extent that they blocked the development of energy resources, were seen as obstructionist, and efforts were made to soften or repeal them. Just as the ESA’s protection of the snail darter interfered with construction of the Tellico Dam, the MMPA’s protection of the bowhead whale was seen as slowing offshore oil exploration in the Arctic Ocean.6 The CZMA, too, came under increasing attack as the federal consistency provisions were frequently called into play by coastal states seeking to ensure that coastal energy activities did not adversely affect their coastal zones. Several lawsuits were brought to determine how far coastal states were required to go in considering/accommodating the national interest in the siting of facilities of more than local significance in coastal areas.7

In 1976, Congress grafted the Coastal Energy Impact Program (CEIP) onto the CZMA in an effort to assist the states as they grappled simultaneously with completing their coastal zone management programs and were pressured to site additional energy-related facilities in their coastal zones (Eliopoulous 1982). But this program did little to ease the tension that was building between coastal management and coastal energy development. By 1978, Congress had completed work on a revised and environmentally sensitive approach to offshore leasing of the outer continental shelf for oil and gas development. The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act Amendments (OCSLAA) of 1978 created a new decision-making process for offshore oil leasing and development in federal waters that ostensibly brought state and local governments into the process (P.L. No. 95-372, 1978). In fact, however, as implementation of the new legislation proceeded, it became clear that the secretary of interior was largely free to ignore state and local recommendations regarding the timing and size of OCS lease sales and specific exploration and development projects (Cicin-Sain and Knecht 1987).

During this period, the federal government encouraged coastal states and oil companies to consider the construction of offshore deepwater ports to service the supertankers carrying imported oil from the Middle East and elsewhere. Federal legislation was enacted in 1974 (P.L. No. 93-627, 1975) and one state, Louisiana, constructed an offshore terminal. The government also sought to foster innovative renewable energy projects such as those based on the concept of ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) (P.L. No. 96-283, 1980).

Although the Law of the Sea negotiations being conducted during this time attracted little public notice, this activity commanded the attention of ocean policy makers in the United States. The objectives of the United States in the Third United Nations Conference on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) negotiations were varied: to stabilize international ocean law; to protect freedom of navigation to the maximum extent possible; to establish clear ownership of the resources of the 200-mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs); and to create a deep-seabed minerals regime that incorporated free-market principles insofar as possible and guaranteed licenses to qualified U.S. companies.

The oil embargoes that occurred during these protracted negotiations gave U.S. mining interests an opportunity to focus attention on a new problem. They argued that the nation, because of its lack of domestic sources, faced a potential...