- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Feed the World

About this book

By 2050, we will have ten billion mouths to feed in a world profoundly altered by environmental change. How can we meet this challenge? In How to Feed the World, a diverse group of experts from Purdue University break down this crucial question by tackling big issues one-by-one. Covering population, water, land, climate change, technology, food systems, trade, food waste and loss, health, social buy-in, communication, and, lastly, the ultimate challenge of achieving equal access to food, the book reveals a complex web of factors that must be addressed in order to reach global food security.

How to Feed the World unites contributors from different perspectives and academic disciplines, ranging from agronomy and hydrology to agricultural economy and communication. Hailing from Germany, the Philippines, the U.S., Ecuador, and beyond, the contributors weave their own life experiences into their chapters, connecting global issues to our tangible, day-to-day existence. Across every chapter, a similar theme emerges: these are not simple problems, yet we can overcome them. Doing so will require cooperation between farmers, scientists, policy makers, consumers, and many others.

The resulting collection is an accessible but wide-ranging look at the modern food system. Readers will not only get a solid grounding in key issues, but be challenged to investigate further and contribute to the paramount effort to feed the world.

How to Feed the World unites contributors from different perspectives and academic disciplines, ranging from agronomy and hydrology to agricultural economy and communication. Hailing from Germany, the Philippines, the U.S., Ecuador, and beyond, the contributors weave their own life experiences into their chapters, connecting global issues to our tangible, day-to-day existence. Across every chapter, a similar theme emerges: these are not simple problems, yet we can overcome them. Doing so will require cooperation between farmers, scientists, policy makers, consumers, and many others.

The resulting collection is an accessible but wide-ranging look at the modern food system. Readers will not only get a solid grounding in key issues, but be challenged to investigate further and contribute to the paramount effort to feed the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Feed the World by Jessica Eise, Ken Foster, Jessica Eise,Ken Foster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Agribusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Inhabitants of Earth

Brigitte S. Waldorf

The world’s growing population is more than a matter of numbers.

“How many children do you wish to have?”

This is the first question I ask in my classes on population. Hundreds of students have answered this over my many years of teaching. The vast majority of responses range between zero and two.

But there is almost always one student in class—without exception it has been, thus far, a male student—who wants to have many kids. His answer of “five or six” inevitably triggers a very interesting conversation on the pros and cons of large family sizes. The expense of raising a child is typically their main reason against many kids. In the United States, these costs are estimated1 to range between $12,350 and $13,900 per year for a child living in a middle-income, two-child, married-couple family, and this does not include the social investments made in children for things like public health and education.

After this, our class conversation generally turns to awareness of and access to birth control, contraceptive failure, and unintended pregnancies. At last, we branch out to the question of how our own individual fertility decisions will impact the world’s population growth. It is this, our growing, global population, which is the great matter of concern. Yet few of us think about how our tiny, personal fertility decisions (which don’t feel tiny to us at all, coincidentally) contribute to the giant, increasing ticker that measures the quantity of people living on our planet. What even fewer of us think about is that the matter of population is not nearly so simple as how many kids we have or plan on having. There are important follow-up questions we must answer, such as, Where do you plan on living? How old are you going to get? How long can your children expect to live?

It comes as a surprise to many that our personal life choices—beyond how many offspring we wish to have—influence population. Not smoking, eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and following all the doctors’ advice influence our lifespan. Those extra years we add to our time on Earth will, ultimately, also impact how large the world population is and how fast it will grow.

As I explain to my classes, these choices and decisions, such as eating well or going to the doctor, arise from a place of privilege wrought from a certain socioeconomic status. To decide how many children to have, and how to live, demands a degree of education and economic power. Yet not everyone shares similar privileges. Not everyone can choose. It sounds paradoxical but, as we’ll see, not having a choice can have an even greater, and sometimes undesirable, impact on the world’s population growth.

One area in which this manifests quite keenly is women’s reproduction. The United Nations reports that in certain African countries the availability of contraceptives (such as condoms and other means of birth control) is very low. There is a huge, unmet need for family planning.2 Without contraceptives, having kids “just happens.” It is not a surprise that these countries also have the highest fertility rates (or number of births in a woman’s lifetime) in the world.

Another space in which we see this is death. With respect to mortality, the desire to live longer is certainly universal. But in many parts of the world, people don’t have the luxury to contemplate their health, lifestyles, environmental quality, and long-term well-being. The urgent need to simply survive in the here and now overshadows these concerns. Filling an empty stomach in that exact moment is what counts, especially when you can’t be sure of the next opportunity to do so.

Whether wrought by choice or circumstance, these individual behaviors are embedded in a broader context. This broader context is shaped by many factors, such as the environment, economy, and policies. The chapters in this book delve into these issues, and, as you sift through the pages, you can well imagine how some of these challenges influence population levels. Environmental factors such as desertification and soil degradation reduce the amount of food farmers can grow on their land, which in turn diminishes the population that can be sustained. Even more extreme is the complete loss of arable land along the coasts and rivers as a result of climate change–induced sea level rise.

With the broader context taken into consideration, population experts agree we will likely hit about 10 billion people by the year 2050. Yet what does that number even mean? Can we achieve global food security and improve nutrition with so many people on Earth? How can we do so? When will we be able to do so, and what limits humankind’s ability to achieve global food security?

Concern about our ability to provide sufficient food for the planet’s growing population is at the center of the population debate. The food–population nexus is full of intricate nuances. Issues vary across countries and people. And the complexities only increase as population numbers are subjected to, and contribute to, an uncertain future in a world of elaborate political threads, environmental problems, and climate change. Planning for a future in this complex, multifaceted web of population, food, environment, and climate is a monumental task. The manner in which we confront the uncertainties surrounding future population change underpins the entire food debate.

On the Rise

The world population has been, for the most part, growing ever since the first agricultural revolution about 10,000 years ago. This was when humans began to transition from hunting and gathering to settled agriculture. Growth was slow and steady for the next eight millennia, but for a few calamitous interruptions along the way. The most well known of these is the Great Plague in Eurasia in the fourteenth century. As disease swept the continent, a shocking portion of the population died, with estimates running from 20 to 50 percent and higher in some areas.

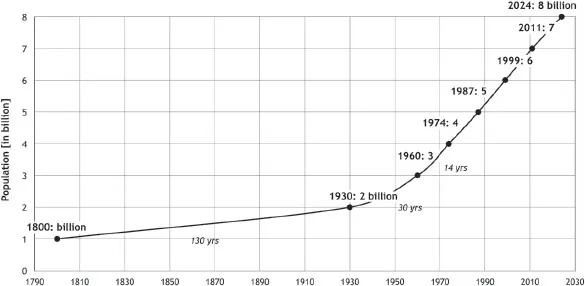

But aside from these few exceptions, caused by epidemics such as the Great Plague or prolonged wars, the population growth was very slow and barely noticeable. There were but a few million people at the beginning of the first agricultural revolution. From that point, it took approximately 8,000 years for numbers to grow and hit one billion in 1800. Yet once that first billion was hit, growth skyrocketed. Adding the second billion took 130 years: by 1930, we had doubled our population in less than 2 percent of the time it had taken us to get from the first agricultural revolution to one billion.

Then, in less than a hundred years, we jumped from two to nearly eight billion people (fig. 1.1). As the graph shows, the time needed to reach each consecutive billion became shorter and shorter, plateauing somewhat over the past 50 years. Without giving too much away, since I was born, our population has grown by literally billions. The same can be said for you! Today, 7.6 billion people share our planet. And just this year alone, we will welcome 83 million. That is far more than twice the entire Canadian population alone. The additional 83 million people per year need shelter, health care, education, jobs, transportation, clean air, and clean water. And, of course, food.

It is expected that the threshold of 8 billion will be reached just a few short years from now, at the end of 2022. While I mentioned earlier that experts predict 10 billion by 2050, that is still a rough estimate. Why? It is not simple to predict population growth. Any statement about how the population size will change in the future is filled with uncertainty. These estimates require us to make assumptions about future demographic behaviors and patterns. That is, we need to sketch out scenarios to describe how we will behave.

Figure 1.1. From one to eight billion in 225 years.

The United Nations has made projections under different scenarios.3 First, imagine a scenario where both fertility and life expectancy remain as they were during the recent past. This is the United Nations’ “no-change scenario.” It is a benchmark for comparison. The result is an astounding 19.7 billion inhabitants on Earth by 2100. This is an additional 12 billion people, or more than two and a half times as many people as currently inhabit Earth. Once we delve into the specifics of providing housing and food for an additional 12 billion people in just 80 years, it becomes quite clear that this scenario would make the twenty-first century extraordinary, to say the least.

Yet we likely won’t face such a scenario. Assuming “no change” in demographic patterns would be entirely counter to what has played out in the past centuries. The past 300 years have shown us how drastically demographic patterns can change, and how differently they play out in different places.

To better understand this, let’s look at England. England was the first country to go through the demographic transition from high mortality and high fertility to low mortality and low fertility. Simply put, they were the first population to shift from dying young and having a lot of babies, to living a long time and not having that many babies.

After the onset of industrialization, England’s mortality dropped in large part due to the major decline in deaths from infectious diseases, such as cholera, smallpox, and typhus. Improved sanitation, medical advances, and an improved food supply contributed to this decline. Because of these improvements, the population grew quite rapidly at first. In fact, it more than doubled in the early half of the 1800s.

Yet this trend was short-lived. Toward the end of the 1800s, fertility rates began to decline sharply. In 1871, English women had, on average, 5.5 babies each. Fifty years later, they had an average of only 2.4 babies.4 This decline happened even before the emergence of modern contraceptives, such as the birth control pill in the 1960s.

To better grasp this, imagine the following scenario. Mary, a British homemaker in 1867, is 33 years old and has seven children all under the age of 16. Her neighbors’ families are all, more or less, the same size too. She, her husband Frank, and their children all benefit from the better sanitation, medical treatments, and food supply wrought by industrialization. As the years roll past, something happens that in earlier years was nearly unheard of—only one of Mary’s seven children dies during childhood. Mary’s children soon grow up and have children of their own. Fast forward to the roaring 1920s. Mary is still alive, now an old woman, and is surprised that her children and grandchildren have kept their families so small. Not one of her progeny has more than four children, and some don’t even have any at all!

Mary lived through what we now understand to be a common demographic shift for high-income countries. Today, England has long since completed this transition. Life expectancy is very high, at 81 years, and fertility is quite low, at 1.9 babies per woman. This is even below the replacement level of 2.1 babies, the number of children needed to keep a population stable.

All high-income countries5 over the past century and a half have followed this very same trend at slightly different times. It is a transition into what we call a “low mortality/low fertility regime.” In some countries today, the declines are even more drastic than what we see in England. Take Japan, for instance. The Japanese can expect to live two years longer than the British, and Japanese women have an average of only 1.4 babies.

To many, this initially feels counterintuitive. As the standard of living rises, and there is a lower chance of mortality, we technically have more money to raise kids and we don’t have to deal so frequently with the horrors of dying young, or watching children die young. Nonetheless, we have fewer kids. And middle-income countries are well on their way to following this same trend. World Bank data6 suggest that life expectancy in Mexico climbed from 57 years in 1960 to 77 years in 2014. Due to successful government-sponsored family planning programs, during that same time period Mexican fertility dropped from 6.8 to 2.2 babies born per woman.

Similar developments are being observed in lower-middle income countries. In Myanmar, for example, life expectancy increased from 43 to 66 years between 1960 and 2014, whereas the number of babies born decreased from 6.1 to 2.2 per woman. In low-income countries, life expectancy has already increased whereas fertility is only starting to decline. In Mozambique, for instance, people now live 55 years on average, up from 35 years in 1960. Yet the number of babies born per woman only slightly dropped so far, from 6.6 babies to 5.4.

These changes are the reason why the “no-change scenario” and its prospect of 19.7 billion people in 2100 is such an unrealistic outcome. It is far more realistic to think about scenarios that allow for declines in both mortality and fertility, especially the latter. The issue is, what are reasonable assumptions about the speed of the mortality decline? And what is a good estimate for the speed of fertility decline in the middle and low income countries?

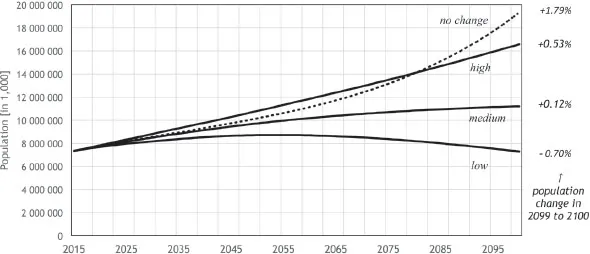

Given these complexities, in addition to the no-change scenario, the United Nations also projects other scenarios for the world’s future population that take into account varying degrees of declining mortality and fertility. The chart here shows three of these projections (fig. 1.2). Each makes different assumptions about the fertility decline. They are labeled as low, medium, and high (as well as the no change projection). The projections start in 2015 and extend to the end of the century. As you can see, differences among them emerge quite early. After just 20 years, the projections for high fertility and low fertility already differ by almost one billion people.

In the low-fertility scenario, one in which population experts track what they guess will be the lowest probable rates of fertility and mortality, the population never even reaches nine billion. In fact, it already starts declining by 2053. It further projects that by 2100 the population will be even smaller than it is today.

Yet in the high-fertility scenario, where researchers assume the higher end of probable fertility and mortality, the projected population figures exceed those of the no-change scenario for the first 62 years before dipping down below and reaching 16.5 billion in 2100. The medium-fertility scenario, the most commonly cited scenario, projects 9 billion people at the end of 2036, 10 billion at the end of 2054, and 11 billion in 2088. It is not as extreme as the high-fertility and no-change projections. This medium scenario also predicts that population growth will slow substantially as we reach the end of the century. In fact, its growth rate during the last year of the twenty-first century is close to zero (0.09 percent), hinting that population growth will level off in the twenty-second century, or even come to a total standstill.

A note of caution, however. The thing that makes population projections so tricky is all the uncertainty, and the uncertainty grows the further we look down the line. A disease outbreak, for example, can throw these projections completely off kilter. HIV and AIDS have, in some countries, slowed or even stopped the downward trend in mortality. Other recent examples include the Ebola outbreak in western Africa, and the emergence of a deadly flu virus similar to the Spanish flu H1N1 influenza virus that spread in 1918–19 and killed millions of people. Public health officials are particularly concerned about this. Such a virus can, in our globalized world, easily cause a pandemic with devastating consequences, including large population losses. Don’t panic yet though, because successful vaccination programs can and have lowered mortality worldwide. Improvements in quantity and quality of the food supply do the same.

Figure 1.2. Population projections of the United Nations.

Yet it is not just mortality, or unexpected deaths, that affect projections. There are unforeseen fluctuations in fertility. China recently loosened its one-child policy, allowing women to have a second child. There are more than a quarter billion Chinese women of reproductive age (15 to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Inhabitants of Earth

- Chapter 2 The Green, Blue, and Gray Water Rainbow

- Chapter 3 The Land That Shapes and Sustains Us

- Chapter 4. Our Changing Climate

- Chapter 5 The Technology Ticket

- Chapter 6 Systems

- Chapter 7 Tangled Trade

- Chapter 8 Spoiled, Rotten, and Left Behind

- Chapter 9 Tipping the Scales on Health

- Chapter 10 Social License to Operate

- Chapter 11 The Information Hinge

- Chapter 12 Achieving Equal Access

- Conclusion

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Contributors

- Index