eBook - ePub

Three Revolutions

Steering Automated, Shared, and Electric Vehicles to a Better Future

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Three Revolutions

Steering Automated, Shared, and Electric Vehicles to a Better Future

About this book

For the first time in half a century, real transformative innovations are coming to our world of passenger transportation. The convergence of new shared mobility services with automated and electric vehicles promises to significantly reshape our lives and communities for the better—or for the worse.

The dream scenario could bring huge public and private benefits, including more transportation choices, greater affordability and accessibility, and healthier, more livable cities, along with reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The nightmare scenario could bring more urban sprawl, energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and unhealthy cities and individuals.

In Three Revolutions, transportation expert Dan Sperling, along with seven other leaders in the field, share research–based insights on potential public benefits and impacts of the three transportation revolutions. They describe innovative ideas and partnerships, and explore the role government policy can play in steering the new transportation paradigm toward the public interest—toward our dream scenario of social equity, environmental sustainability, and urban livability.

Many factors will influence these revolutions—including the willingness of travelers to share rides and eschew car ownership; continuing reductions in battery, fuel cell, and automation costs; and the adaptiveness of companies. But one of the most important factors is policy.

Three Revolutions offers policy recommendations and provides insight and knowledge that could lead to wiser choices by all. With this book, Sperling and his collaborators hope to steer these revolutions toward the public interest and a better quality of life for everyone.

The dream scenario could bring huge public and private benefits, including more transportation choices, greater affordability and accessibility, and healthier, more livable cities, along with reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The nightmare scenario could bring more urban sprawl, energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and unhealthy cities and individuals.

In Three Revolutions, transportation expert Dan Sperling, along with seven other leaders in the field, share research–based insights on potential public benefits and impacts of the three transportation revolutions. They describe innovative ideas and partnerships, and explore the role government policy can play in steering the new transportation paradigm toward the public interest—toward our dream scenario of social equity, environmental sustainability, and urban livability.

Many factors will influence these revolutions—including the willingness of travelers to share rides and eschew car ownership; continuing reductions in battery, fuel cell, and automation costs; and the adaptiveness of companies. But one of the most important factors is policy.

Three Revolutions offers policy recommendations and provides insight and knowledge that could lead to wiser choices by all. With this book, Sperling and his collaborators hope to steer these revolutions toward the public interest and a better quality of life for everyone.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Three Revolutions by Daniel Sperling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Will the Transportation Revolutions Improve Our Lives—or Make Them Worse?

Daniel Sperling, Susan Pike, and Robin Chase

We must steer oncoming innovations toward the public interest—toward shared, electric, automated vehicles. If we don’t, we risk creating a nightmare.

WE LOVE OUR CARS. OR AT LEAST we love the freedom, flexibility, convenience, and comfort they offer. That love affair has been clear and unchallenged since the advent of the Model T a century ago. No longer. Now the privately owned, human-driven, gasoline-powered automobile is being attacked from many directions, with change threatening to upend travel and transportation as we know it. The businesses of car making and transit supply—never mind taxis, road building, and highway funding—are about to be disrupted. And with this disruption will come a transformation of our lifestyles. The signs are all around us.

Maybe you use Zipcar, Lyft, or Uber or know someone who does. You’ve probably seen a few electric vehicles (EVs) on the streets, mostly Nissan Leafs, Chevy Volts and Bolts, Teslas, and occasionally others. And you’ve undoubtedly heard and read stories about self-driving cars coming soon and changing everything. But how fast are the three revolutions in electric, shared, and automated vehicles happening, and will they converge? Will EVs become more affordable and serve the needs of most drivers? Will many of us really be willing to discard our cars and share rides and vehicles with others? Will we trust robots to drive our cars?

We’re at a fork in the road.

Over the past half century, transportation has barely changed. Yes, cars are safer and more reliable and more comfortable, but they still travel at the same speed, still have the same carrying capacity, and still guzzle gasoline with an internal combustion engine. Public transit hasn’t changed much either, though modern urban rail services have appeared in some cities since the 1970s. Likewise, roads are essentially unchanged, still made with asphalt and concrete and still funded mostly by gasoline and diesel taxes. We have a system in which our personal vehicles serve all purposes, and all roads serve all vehicles (except bicycles). It is incredibly expensive, inefficient, and resource intensive.

But it’s even worse than that. Most cars usually carry only one person and, most wasteful of all, sit unused about 95 percent of the time.1 As wasteful and inefficient as they are, cars have largely vanquished public transit in most places. Buses and rail transit now account for only 1 percent of passenger miles in the United States.2 Those who can’t drive because they’re too young, too poor, or too physically diminished are dependent on others for access to basic goods and services in all but a few dense cities.

Starting in Los Angeles, the United States built this incredibly expensive car monoculture, and it is being imitated around the world. Cars provide unequaled freedom and flexibility for many but at a very high cost. Owners of new cars in the United States spend on average about $8,500 per vehicle per year, accounting for 17 percent of their household budgets.3 On top of that is the cost to society of overbuilt roads, deaths and injuries, air pollution, carbon emissions, oil wars, and unhealthy lifestyles. The statistics are mind-numbing. For the United States alone, consider that nearly 40,000 people were killed and 4.6 million seriously injured in 2016 in car, motorcycle, and truck accidents.4 Nearly ten million barrels of oil are burned every day in the United States by our vehicles.5 Transportation accounts for a greater proportion of greenhouse gases than any other sector.6 Farther afield, in Singapore, 12 percent of the island nation’s scarce land is devoted to car infrastructure.7 In Delhi, 4.4 million children have irreversible lung damage because of poor air quality, mostly due to motor vehicles.8 We have created an unsustainable and highly inequitable transportation system.

But change is afoot, finally. For the first time since the advent of the Model T one hundred years ago, we have new options. The information technology revolution, which transformed how we communicate, do research, buy books, listen to music, and find a date, has finally come to transportation. We now have the potential to transform how we get around—to create a dream transportation system of shared, electric, automated vehicles that provides access for everyone and eliminates traffic congestion at far less cost than our current system. Or not. It could go awry. It could turn out to be a nightmare.

Let’s take a minute to imagine two different scenarios set in the year 2040.

Transportation 2040: The Dream

In one vision of the future, the government has managed to steer the three revolutions toward the common good with forward-thinking strategies and policies. Citizens have the freedom to choose from many clean transportation options. They can spend their time with family and friends rather than in traffic thanks to pooled automated cars. They breathe cleaner air, worry less about greenhouse gas emissions, and trust that transportation is safer, more efficient, and more accessible than ever before. The search for parking is an inconvenience of the past. Worries about Grandma being homebound have evaporated. No longer must parents devote hours to ferrying their kids everywhere. Transportation innovations have made it easy for people to meet all their transportation needs conveniently and at a reasonable cost.

On a typical day in this optimistic scenario, Patricia Mathews and Roberto Ruiz eat breakfast at home with their two children before Pat is picked up by an electric automated vehicle (AV) owned by a mobility company. The AV is dispatched from a mobility hub, where trains come and go, bikes are available, and AVs pick up and drop off passengers.

Like most homes in the neighborhood, the Mathews-Ruiz home has a small pickup area and vegetable garden in front, replacing what had been a large driveway. The garage has been converted to a guest room. Parks and public gardens are connected in a greenbelt that runs behind the homes. Children scamper around without parents worrying about traffic.

As Pat approaches the dispatched AV, it recognizes her and opens a door. Her unique scan authorizes a secure payment mediated through blockchain from her family’s mobility subscription account, which also pays for transit, bikeshare, and other transportation services. For a small monthly fee, plus a per-mile charge, the family gains access to a variety of shared vehicles and services, including AVs, electric scooters, and intercity trains. Discounts are also available for special services like air travel. The account isn’t connected to a traceable bank account, and travel data are erased every two months.

As Pat settles in for the short commute, the AV is notified to pick up one more passenger along the way, a neighbor Pat knows. On the way into the city, they chat about the upcoming neighborhood block party. The AV picks up another passenger and heads to the city center, where it is routed onto a broad boulevard with two lanes for auto travel, a reserved lane in the middle for trucks and buses, and bike lanes on each side, flanked by wide pedestrian walkways.

The rest of the Mathews-Ruiz family heads out on shared-use bicycles to the children’s school (with AVs available as backup on rainy days). Roberto continues on to the fitness center where he works. It takes him about twenty minutes. At lunchtime, Roberto will hop on a shared electric bike to meet his mother for lunch on the other side of town. She lives in a little neighborhood with a dense mix of shops and residences. Street parking was removed years ago and replaced with a sprinkling of passenger-loading and goods-delivery spaces, extensive bike pathways, wide sidewalks, outdoor seating, and pocket parks.

After lunch, Roberto helps his mother arrange a ride to a nearby medical center in an AV specially designed for physically limited passengers. On her way home, she will be dropped off to visit one of her friends. Her retirement income easily covers her mobility subscription and gives her and other low-income citizens many options for travel. For those with less income, subscription subsidies are available. The subsidies go further if the travelers use AVs during off-peak hours, when many AVs are being parked and recharged. AV dispatching is optimized to match shifts in demand, and travel is priced accordingly.

Back at work, Pat calls Roberto to make plans for the evening. The kids will return from school with a bicycle group and meet their babysitter. Roberto and Pat will hail an AV to go to dinner at one of the pop-up restaurants in the neighborhood park—knowing that if they drink too much, they won’t need to worry about driving themselves home.

Transportation 2040: The Nightmare

Now imagine the very different future that could come about if our community is unprepared for the three revolutions. Instead of adopting policies and incentives to encourage pooling of rides, the city allows the private desires of individuals and the competitive instincts of automotive companies to prevail. Traffic congestion gets worse as people who can afford AVs indulge themselves and send their cars out empty on errands. Most AVs are not electrified, and greenhouse gas emissions increase as people travel more. Time to spend with children and engage in community service becomes scarce. Transit services diminish as rich commuters abandon buses and rail and withdraw their support for transit. Those without driver’s licenses and cars continue to be marginalized as the divide between mobility haves and have-nots becomes a chasm. Meanwhile, suburbs sprawl as people seek affordable homes farther and farther out, opting for long commutes and cheap mortgages over proximity and more expensive real estate.

In this future, the middle-class Mathews-Ruiz family owns their own AV, which they’ve named Hal after the all-powerful computer in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. They live in the outer reaches of suburbia in a modest home. With vehicles still personal property (a residue of the twentieth century) and public transportation minimal, the family is trapped into spending nearly half their income on their beloved AV. They pay not only the high cost of the vehicle but also substantial expenses for remote parking (when not at home), required software updates, safety checks for software and hardware, and access to special AV lanes.

Their eighty-mile commute to jobs in the city center consumes about an hour and a half each way. When they pay to use a special AV lane, Hal can cruise at eighty miles per hour, but the trip is slowed down by Hal’s having to drive on mixed-use lanes to and from the high-speed freeway. And on some days, they opt for the mixed-use lanes on their way to and from work to reduce their toll costs, increasing their commute time to two hours each way.

The family buys an AV lane pass that allows them three thousand miles per month, after which they pay $0.40 per mile. With their eighty-mile commute, they use up the entire allocation each month just getting to and from work, forcing them to pay the higher off-subscription rates for the rest of the miles they log.

On days when one of them works late, they send Hal back empty to fetch that other person, or whoever finishes work earlier bides his or her time meandering in Hal along the streets in the crowded, congested city center. But the car is comfortable and the rider can use the time productively (even napping!).

Hal accrues still more miles traveling to pick up the children in the afternoon and running errands during the day. These errands might include a trip to pick up packages at a warehouse, where Hal is recognized with scanning technology and robots load and unload boxes. With all this travel, plus weekend recreation, Hal’s mileage generally exceeds five thousand miles per month.

The Fork in the Road

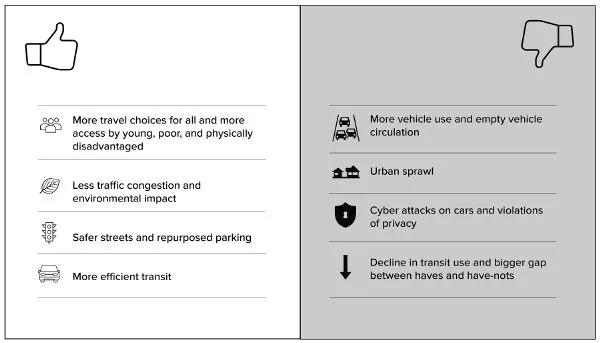

Will either of these futures materialize? Will the three revolutions usher in more vehicle use, increased urban sprawl, more marginalization of mobility have-nots, more expensive transportation, and higher greenhouse gas emissions? Or will they lead to reduced congestion and environmental impacts, safer communities, and easier and cheaper access for all (see figure 1.1)? The answer is unknown and will likely vary greatly across regions and countries. The three revolutions will unfold at different speeds in different places, creating waves of unintended—or at least unanticipated—consequences. We do have a say, but only if we wake up now to the speed and scope of change and how the coming revolutions will impact mobility and cities. Decisions made now about infrastructure and vehicle technologies will strongly influence the path and speed of change (a concept known as path dependence).

Figure 1.1. The fork in the road: Will transportation in 2040 be a dream or a nightmare?

Two of these revolutions—vehicle electrification and automation—are inevitable. The third, pooling, is less certain but in many ways most critical, especially as AVs come into being. All three have the potential to offer large benefits. EVs, including those powered by hydrogen, will decrease the use of fossil fuels and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Shared use of vehicles will reduce the number of cars on the road and thus congestion and emissions. Automation, in most cases, will reduce crashes. These benefits will be fully realized—indeed, enhanced—only if the three revolutions are integrated. Integration means EVs carrying multiple occupants under automated control. The result will be low-cost, low-carbon, equitable transportation.

Will this integration—the dream scenario—come about? As Automotive News, the principal trade magazine of the auto industry, put it, “There are millions of ways that flawed, messy, sometimes inconsiderate humans can mess up a perfectly good utopian scenario.”9 Many factors will shape the future, including how willing consumers are to accept new services and to share rides, how open transit operators are to embracing new mobility services as complements to their bus and rail services, and how inclined automakers are to become mobility companies instead of just car companies. Equally important will be the myriad policy, regulatory, and tax decisions m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Will the Transportation Revolutions Improve Our Lives—or Make Them Worse?

- Chapter 2. Electric Vehicles: Approaching the Tipping Point

- Chapter 3. Shared Mobility: The Potential of Ridehailing and Pooling

- Chapter 4. Vehicle Automation: Our Best Shot at a Transportation Do-Over?

- Chapter 5. Upgrading Transit for the Twenty-First Century

- Chapter 6. Bridging the Gap between Mobility Haves and Have-Nots

- Chapter 7. Remaking the Auto Industry

- Chapter 8. The Dark Horse: Will China Win the Electric, Automated, Shared Mobility Race?

- Epilogue. Pooling Is the Answer

- Notes

- About the Contributors

- Index