Panarchy

Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems

- 536 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Panarchy

Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems

About this book

Creating institutions to meet the challenge of sustainability is arguably the most important task confronting society; it is also dauntingly complex. Ecological, economic, and social elements all play a role, but despite ongoing efforts, researchers have yet to succeed in integrating the various disciplines in a way that gives adequate representation to the insights of each.

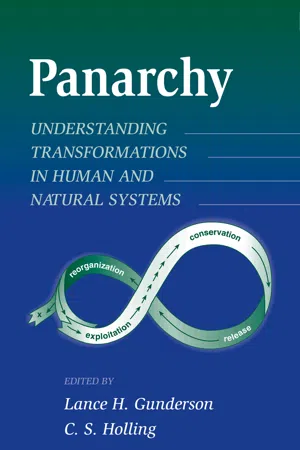

Panarchy, a term devised to describe evolving hierarchical systems with multiple interrelated elements, offers an important new framework for understanding and resolving this dilemma. Panarchy is the structure in which systems, including those of nature (e.g., forests) and of humans (e.g., capitalism), as well as combined human-natural systems (e.g., institutions that govern natural resource use such as the Forest Service), are interlinked in continual adaptive cycles of growth, accumulation, restructuring, and renewal. These transformational cycles take place at scales ranging from a drop of water to the biosphere, over periods from days to geologic epochs. By understanding these cycles and their scales, researchers can identify the points at which a system is capable of accepting positive change, and can use those leverage points to foster resilience and sustainability within the system.

This volume brings together leading thinkers on the subject -- including Fikret Berkes, Buz Brock, Steve Carpenter, Carl Folke, Lance Gunderson, C.S. Holling, Don Ludwig, Karl-Goran Maler, Charles Perrings, Marten Scheffer, Brian Walker, and Frances Westley -- to develop and examine the concept of panarchy and to consider how it can be applied to human, natural, and human-natural systems. Throughout, contributors seek to identify adaptive approaches to management that recognize uncertainty and encourage innovation while fostering resilience.

The book is a fundamental new development in a widely acclaimed line of inquiry. It represents the first step in integrating disciplinary knowledge for the adaptive management of human-natural systems across widely divergent scales, and offers an important base of knowledge from which institutions for adaptive management can be developed. It will be an invaluable source of ideas and understanding for students, researchers, and professionals involved with ecology, conservation biology, ecological economics, environmental policy, or related fields.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

IN QUEST OF A THEORY OF ADAPTIVE CHANGE

In all things, the supreme excellence is simplicity.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, cascades of changes occurred on a global scale. Collapse of the former Soviet Union and its continuing struggle for stability and for ways to restructure have propagated international reverberations far beyond its borders. Increases in connectivity through the Internet are stimulating a flowering of novel experiments that are affecting commerce, science, and international community. Migrations of people, some forced by political upheaval and some initiated as a search for new opportunity, are both threatening and enriching the international order. There have been dramatic changes in global environmental systems—from climate change that is already upon us, to the thinning of the stratospheric ozone layer. Novel diseases have emerged in socially and ecologically disturbed areas of the world and have spread globally, through the increased mobility of people. The tragedy of AIDS, and its origins, transformation, and dispersion because of land-use and social changes, is a signal of deep and broad changes that will yield further surprises and crises. More and more evidence indicates that global climate change has already produced an increase in severe weather that, combined with inappropriate coastal development, has caused dramatic rises in insurance claims and human loss of life. Still other more subtle changes linking ecological, economic, and social forces are occurring on a global scale, such as the typical example described in Box 1-1, regarding the collapse of fisheries.

Box 1-1. Fishing down the Food Web

Although total catch levels for marine fisheries have been relatively stable in recent decades, analysis of the data shows that landings from global fisheries have shifted from large piscivorous fishes toward smaller invertebrates and planktivores (Pauly et al. 1998). This shift can be quantified through assignment of a fractional trophic level to each species, depending on the composition of the diet. The values of these trophic levels range from 1 for primary producers to over 4.6 for a few top predators such as a tuna in open water and groupers and snappers among bottom fishes. For data aggregated over all marine areas, the trend over the past forty-five years has been a decline of the mean trophic level from over 3.3 to less than 3.1. In the Northwest Atlantic, the mean trophic level is now below 2.9. There is not much room for further decreases, since most fish have trophic levels between 3 and 4. Indeed, many fisheries now rely on invertebrates, which tend to have low trophic levels.

- Some fisheries have collapsed in spite of widespread public support for sustaining them and the existence of a highly developed theory of fisheries management.

- Moderate stocking of cattle in semiarid rangelands has increased vulnerability to drought.

- Pest control has created pest outbreaks that become chronic.

- Flood control and irrigation developments have created large ecological and economic costs and increasing vulnerability.

- Paradox 1. The Pathology of Regional Resource and Ecosystem Management Observation: New policies and development usually succeed initially, but they lead to agencies that gradually become rigid and myopic, economic sectors that become slavishly dependent, ecosystems that are more fragile, and a public that loses trust in governance.

The Paradox: If that is as common as it appears, why are we still here? Why has there not been a profound collapse of exploited renewable resources and the ecological services upon which human survival and development depend?

The observed pattern of failure can be analyzed from an economic and human behavioral standpoint. According to one view, resources are appropriated by powerful minorities able to influence public policy in ways that benefit them. Hence inappropriate measures such as perverse subsidies are implemented that deplete resources and create inefficiencies (Magee, Brock, and Young 1989). A fundamental cause of the failures is the political inability to deal with the needs and desires of people and with rent seeking by powerful minorities.

But as part of the fundamental political causes of failure, there are, as well, contributing causes in the way many, including scientists and analysts, study and perceive the natural world. Their results can provide unintended ammunition for political manipulation. Some of this ammunition comes from the very disciplines that should provide deeper and more integrative understanding, primarily economics, ecology, and institutional analysis. That leads to the second paradox: the trap of the expert. So much of our expertise loses a sense of the whole in the effort to understand the parts. - Paradox 2. The Trap of the Expert Observation: In every example of crisis and regional development we have studied, both the natural system and the economic components can be explained by a small set of variables and critical processes. The great complexity, diversity, and opportunity in complex regional systems emerge from a handful of critical variables and processes that operate over distinctly different scales in space and time.

The Paradox: If that is the case, why does expert advice so often create crisis and contribute to political gridlock? Why, in many places, does science have a bad name?

Partial Truths and Bad Decisions

Economics

Ecology

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- List of Tables

- LIST OF BOXES

- PREFACE

- Acknowledgments

- Part I - Introduction

- Part II - Theories of Change

- Part III - Myths, Models, and Metaphors

- Part IV - Linking Theory to Practice

- Part V - Summary and Synthesis

- APPENDIX A. - A MODEL FOR ECOSYSTEMS WITH ALTERNATIVE STABLE STATES

- APPENDIX B. - OPTIMIZING SOCIAL UTILITY FROM LAKE USE

- APPENDIX C. - TAX AS A WAY TO DIRECT SOCIETY

- APPENDIX D. - COLLECTIVE ACTION PROBLEMS AND THEIR EFFECT ON POLITICAL POWER

- REFERENCES

- LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

- INDEX

- ISLAND PRESS BOARD OF DIRECTORS