- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Biophilic Cities redefines what it means to create truly sustainable urban environments—placing nature, not just efficiency, at the heart of the vision. Tim Beatley, a longtime advocate for greener cities, argues that while efforts like public transit, renewable energy, and efficient buildings are important, they often overlook something essential: the human need for connection with the natural world.

Rooted in the biophilia hypothesis—the idea that people are wired to seek relationships with nature—Beatley makes the case that cities must do more than be livable; they must be deeply, deliberately connected to natural systems. A biophilic city, he explains, is not only biodiverse but designed to celebrate and integrate natural forms and processes at every level—from buildings and streetscapes to urban planning and regional design.

Drawing on inspiring case studies from cities around the world, Biophilic Cities explores how urban areas are embracing nature through green roofs and walls, sidewalk gardens, ecological corridors, and citywide greenspace networks. Beatley shares the stories of planners, architects, and everyday citizens who are reshaping cities into places where people and nature thrive side by side.

This book is both a call to action and a guide for anyone seeking to transform grey, hardscaped environments into vibrant, restorative, and resilient urban ecosystems.

Rooted in the biophilia hypothesis—the idea that people are wired to seek relationships with nature—Beatley makes the case that cities must do more than be livable; they must be deeply, deliberately connected to natural systems. A biophilic city, he explains, is not only biodiverse but designed to celebrate and integrate natural forms and processes at every level—from buildings and streetscapes to urban planning and regional design.

Drawing on inspiring case studies from cities around the world, Biophilic Cities explores how urban areas are embracing nature through green roofs and walls, sidewalk gardens, ecological corridors, and citywide greenspace networks. Beatley shares the stories of planners, architects, and everyday citizens who are reshaping cities into places where people and nature thrive side by side.

This book is both a call to action and a guide for anyone seeking to transform grey, hardscaped environments into vibrant, restorative, and resilient urban ecosystems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biophilic Cities by Timothy Beatley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

The Importance of Nature and Wildness in Our Urban Lives

For several years now I have been administering an interesting slide-based survey to my new graduate students. I call it the “what is this?” survey, and it consists largely of images of flora and fauna native to the eastern United States. Interspersed are other images, political and corporate. I ask students to tell me everything they can about the images I present, and the results are usually rather discouraging: Few students are able to name even common species of birds, plants, or trees. Sometimes the results are amusing (and would be more so if they weren't so sad).

One image I present is of a silver-spotted skipper, a very common species of butterfly. Many students identified it as a moth (not unreasonable), some a monarch butterfly (it looks nothing like a monarch, but apparently this is the only species of butterfly some Americans know of), and several students even thought it was a hummingbird. Only one student in several hundred has correctly identified the species. For me the results confirm what I already knew: For most of the current crop of young adults, nature is fairly abstract and rather general. They grew up in an age of computer games, indoor living, and diminished free time. It is probably not surprising that common species of native flora and fauna are not immediately recognizable, but it is an alarming indicator of how we have become disconnected from nature.

Fortunately the students do not have a blasé attitude about this but, encouragingly, a sense of genuine concern about how poorly they fared on this unusual test.

I'm certainly not the only one to notice the limited knowledge of our youth about the natural world and to wonder what this might bode for the future of community and environment. Paul Gruchow, a notable Midwest writer and essayist, has been one of the most eloquent observers of this trend. He tells the story of the local town weed inspector who arrives at his home, in response to a neighbor's complaint about an unkempt yard, only to be unable to identify any of the offending plants and shrubs in the yard (all of which Gruchow knew, and knew well). More disturbing, Gruchow found that a group of high school seniors he took on a nature walk to a nearby lake were unable to name or recognize even the most common midwestern plants. Gruchow connects this to love, that essential thing that binds and connects us to one another and to the places and natural environments that make up our home. “Can you,” Gruchow asked those students, “imagine a satisfactory love relationship with someone whose name you do not know? I can't. It is perhaps the quintessential human characteristic that we cannot know or love what we have not named. Names are passwords to our hearts, and it is there, in the end, that we will find the room for a whole world.”1

Richard Louv has ignited new concern and debate about this nature disconnect in his wildly popular book Last Child in the Woods, in which he argues that today's kids are suffering from “nature deficit disorder.”2 Too much time spent inside, too much time in front of the TV and computer, too little freedom to explore nature (and too little access to nature in new forms of development), and parental concerns about safety (the “bogeyman syndrome,” as Louv calls it) are all contributing factors to this nature disconnect.

These concerns dovetail with health concerns about our overweight, sedentary children, but for me they represent an even more dire prospect of future generations of adults who don't viscerally or passionately care about nature, are little interested in its protection or restoration, and will miss out on the deeper life experiences that such natural experiences and connections can provide.

These trends, and these profound disconnects from nature in childhood and adulthood, suggest the time is ripe to revisit how we design and plan our communities and cities. There are many reasons to worry about our loss of intimate contact with nature, and they come together to create a compelling argument for a new vision of what cities could be. I draw from the theory and research associated with biophilia and argue that we need to reimagine cities as biophilic cities. A biophilic city is a city abundant with nature, a city that looks for opportunities to repair and restore and creatively insert nature wherever it can. It is an outdoor city, a physically active city, in which residents spend time enjoying the biological magic and wonder around them. In biophilic cities, residents care about nature and work on its behalf locally and globally.

The Power of Nature

That we need daily contact with nature to be healthy, productive individuals, and indeed have coevolved with nature, is a critical insight of Harvard myrmecologist and conservationist E. O. Wilson. Wilson popularized the term biophilia two decades ago to describe the extent to which humans are hardwired to need connection with nature and other forms of life. More specifically, Wilson describes it this way: “Biophilia…is the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms. Innate means hereditary and hence part of ultimate human nature.”3

To Wilson, biophilia is really a “complex of learning rules” developed over thousands of years of evolution and human–environment interaction: “For more than 99 percent of human history people have lived in hunter–gatherer bands totally and intimately involved with other organisms. During this period of deep history, and still further back they depended on an exact learned knowledge of crucial aspects of natural history…. In short, the brain evolved in a biocentric world, not a machine-regulated world. It would be therefore quite extraordinary to find that all learning rules related to that world have been erased in a few thousand years, even in the tiny minority of peoples who have existed for more than one or two generations in wholly urban environments.”4

Stephen Kellert of Yale University reminds us that this natural incli nation to affiliate with nature and the biological world constitutes a “weak genetic tendency whose full and functional development depends on sufficient experience, learning, and cultural support.”5 Biophilic sensibilities can atrophy, and society plays an important role in recognizing and nurturing them.

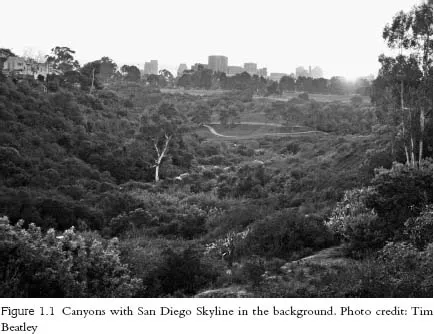

So we need nature in our lives; it is not optional but essential. Yet as the global population becomes ever more urban, ensuring that contact becomes more difficult. While architects and designers are beginning to incorporate biophilia into their work, planners and policymakers who think about cities have lagged behind. The subject at hand raises serious questions about what a city is or could be and what constitutes a livable, sustainable place. I believe there is a need to articulate a theory and practice of city planning that understands that cities and urban areas must be wild and “nature—ful.” Wildness, in this book, refers to urban nature, which is inherently human impacted or influenced. Urban wildness is not wilderness as we have traditionally conceived it in environmental circles. It is not distant and pristine, defined by how little humans have used or impacted it, but nearby and nuanced; it is as much defined by its resilience and persistence in the face of urban pressures. It is the indomitable wind and weather, the plants that sprout and volunteer on degraded sites, the lichen and microorganisms that inhabit and thrive on the façades of buildings, and the turkey vultures and red-tailed hawks that ply the airways and ride thermal currents high above urban buildings. Wildness in this book doesn't mean untouched or removed but instead refers to the many creatures and processes operating among us that are at once fascinating, complex, mysterious, and alive. In the urban epoch more than ever we need creative urban design and planning that makes nature the centerpiece, not an afterthought.

As Stephen Kellert notes, these are unusual times indeed when we actually have to defend and rationalize our need for contact with nature. The profound connection with the natural world has been for most of human history something pretty obvious. Yet today we seem entrenched in the view that we have been able, somehow, to overcome the need for nature, that we can “transcend” nature, perhaps even that we have evolved beyond needing nature.

The empirical evidence of the truth of biophilia, and of social, psychological, pedagogical, and other benefits from direct (and indirect) exposure to nature, is mounting and impressive. Some of the earliest work shows the healing power and recuperative benefits of nature. Roger Ulrich, of Texas A&M University, studied postoperative recovery for gall bladder patients in hospital rooms with views of trees and nature, compared with those with views of walls. Patients with the more natural views were found to recover more easily and quickly: “The patients with the tree view had shorter postoperative hospital stays, had fewer negative evaluative comments from nurses, took fewer moderate and strong analgesic doses, and had slightly lower scores for minor postsurgical complications.”6 These are not surprising results and have helped shift the design of hospitals and medical facilities in the direction of including healing gardens, natural daylight, and other green features.

The body of research confirming the power of nature continues to expand. Research shows the ability of nature to reduce stress, to enhance a positive mood, to improve cognitive skills and academic performance, and even to help in moderating the effects of ADHD, autism, and other childhood illnesses. A recent study by the British mental health charity MIND compared the effects on mood of a walk in nature with a walk in a shopping mall.7 The differences in the effects of these two walks are remarkable though not unexpected. The results show marked improvements in self-esteem following the nature walk (90% improved) but rather small improvements for those walking in the shopping center. Indeed, 44 percent of the indoor walkers actually reported a decline in self-esteem. Similarly, the out-door walk resulted in significant improvements in mood (six factors were measured: depression, anger, tension, confusion, fatigue, and vigor). The different mood effects are especially great with respect to tension. For the outdoor walk, 71 percent of participants reported a reduction in tension (and no increases), while for the indoor walk some 50 percent of the participants actually reported an increase in tension.

Hartig and his colleagues have undertaken a series of studies and experiments that bolster these findings, similarly demonstrating that views of nature and walks in natural settings can reduce mental fatigue, improve test performance, and improve mood (and more so than in urban settings without natural qualities).8 “Views from indoors onto nature can support micro-restorative experiences that interrupt stress arousal or the depletion of attentional capacity. Similarly, when moving through the environment from one place to another, passage through a natural setting may provide a respite that, although brief, nonetheless interrupts a process of resource depletion. Frequent, brief restorative experiences may, over the long run, offer cumulative benefits.”9

This is good news in that the nature in dense, compact cities may be found in smaller doses and in more discontinuous ways (a rooftop garden, an empty corner lot, a planted median) than in nonurban locations. Biophilic urbanism must also strive, of course, for more intensive and protracted exposure to nature (further discussed below), but even the smaller green features we incorporate into cities will have a positive effect.

Few elixirs have the power and punch to heal and restore and rejuvenate the way that nature can. The power of biophilia suggests that everything that we design and build in the future should incorporate natural elements to a far greater extent—indoors and outdoors (and indeed the need to overcome these overly artificial distinctions), green neighborhoods, integrated parks and wild areas, not far away but ideally all around us.

Green Cities, Healthy Cities

Evidence suggests that the presence of green neighborhoods has broader and more pervasive impacts on health than we sometimes appreciate. In a national study involving more than ten thousand people in the Netherlands, researchers found significant and sizable relationships between green elements in living environments and higher levels of self-reported physical and mental health. As the authors conclude, “In a greener environment people report fewer symptoms and have better perceived general health. Also, people's mental health appears better.”10 The level of health was directly correlated to the level of greenness: “10% more greenspace in the living environment leads to a decrease in the number of symptoms that is comparable with a decrease in age by 5 years.”11

A 2007 Danish study demonstrates the importance of access and proximity to parks and nearby greenspaces: These green features were found to be associated with lower stress levels and a lower likelihood of obesity.12

Studies suggest that green features help to draw us outside and propel us to live more physically active lives. Peter Schantz and his colleagues in Stockholm have demonstrated that green features correlate with decisions to walk or bike to work. Schantz refers to these green urban features as “pull factors for physical activity.”13 Leading more physically active lives outdoors will pay tremendous dividends to urbanites in good health. A 2009 survey of ten thousand residents of New York City, the most walkable city in the country, concludes that respondents who walk or bike daily are more likely, even controlling for income, to report being in good health, physically and mentally.14

Many other aspects of community and environmental health are quite effectively addressed through biophilic design and planning. Green urban features, such as trees and green rooftops, serve to address the urban heat island effect and to moderate and reduce urban heat; this has the potential to significantly reduce heat-related stress and illness in cities, something we must worry even more about as many American cities experience a significant rise in summer temperatures. There are, moreover, important air quality benefits from green features, another example of the secondary benefits of trees and urban nature. Trees and plantings on green rooftops, for instance, have been found to significantly reduce air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide and particulates.15

The nature and greenspaces around us also form an important community resource in times of trouble and stress. A 2009 survey by the Trust for Public Land, for instance, concludes that there has been a significant rise in the use of public parks as the national and global economy has soured.16 Perhaps with unemployment on the rise a natural result is that individuals and families have more time to spend in such places, but this trend reinforces the very important role that outdoor nature can play in helping to buttress and buffer families in times of economic and social stress.

The Economics of Biophilia

Evidence suggests that there are very clear economic benefits to these green urban elements. A number of studies have shown that homes with trees, for instance, sell at premium compared with those without trees. A biophilic community is a place where residents can easily get outside, where walking, strolling, and meandering is permissible, indeed encouraged, and evidence suggests that these qualities now carry an economic premium. A 2009 study by CEO for Cities found that homes in more walkable environments carried a price premium of between $4,000 and $34,000 when compared with similar homes in other places.17 Major urban greening projects, like the dramatic daylighting of four miles of the Cheonggycheon River through downtown Seoul, South Korea, which involved the removal of an elevated highway, serve to dramatically enhance the desirability and economic salability for the homes and neighborhoods nearby.18

New green urban elements and features are often rewarded in the marketplace and serve to stimulate new development and redevelopment. Recent examples include the High Line in New York City, the conversion of an elevated freight rail line into a new linear park, and Millennium Park in Chicago; both have stimulated new commercial and residential development, as clear amenity value and overall neighborhood enhancement results from urban greening. The High Line has stimulated an estimated $4 billion in private investment.19

Nature is a significant neighborhood asset and is seen as such by the real estate market. And o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 - The Importance of Nature and Wildness in Our Urban Lives

- Chapter 2 - The Nature of (in) Cities

- Chapter 3 - Biophilic Cities: What Are They?

- Chapter 4 - Biophilic Urban Design and Planning

- Chapter 5 - New Tools and Institutions to Foster Biophilic Cities

- Chapter 6 - Concluding Thoughts: Growing the Biophilic City

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index