- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Peter Gleick knows water. A world-renowned scientist and freshwater expert, Gleick is a MacArthur Foundation "genius," and according to the BBC, an environmental visionary. And he drinks from the tap. Why don't the rest of us?

Bottled and Sold shows how water went from being a free natural resource to one of the most successful commercial products of the last one hundred years—and why we are poorer for it. It's a big story and water is big business. Every second of every day in the United States, a thousand people buy a plastic bottle of water, and every second of every day a thousand more throw one of those bottles away. That adds up to more than thirty billion bottles a year and tens of billions of dollars of sales.

Are there legitimate reasons to buy all those bottles? With a scientist's eye and a natural storyteller's wit, Gleick investigates whether industry claims about the relative safety, convenience, and taste of bottled versus tap hold water. And he exposes the true reasons we've turned to the bottle, from fearmongering by business interests and our own vanity to the breakdown of public systems and global inequities.

"Designer" H2O may be laughable, but the debate over commodifying water is deadly serious. It comes down to society's choices about human rights, the role of government and free markets, the importance of being "green," and fundamental values. Gleick gets to the heart of the bottled water craze, exploring what it means for us to bottle and sell our most basic necessity.

Bottled and Sold shows how water went from being a free natural resource to one of the most successful commercial products of the last one hundred years—and why we are poorer for it. It's a big story and water is big business. Every second of every day in the United States, a thousand people buy a plastic bottle of water, and every second of every day a thousand more throw one of those bottles away. That adds up to more than thirty billion bottles a year and tens of billions of dollars of sales.

Are there legitimate reasons to buy all those bottles? With a scientist's eye and a natural storyteller's wit, Gleick investigates whether industry claims about the relative safety, convenience, and taste of bottled versus tap hold water. And he exposes the true reasons we've turned to the bottle, from fearmongering by business interests and our own vanity to the breakdown of public systems and global inequities.

"Designer" H2O may be laughable, but the debate over commodifying water is deadly serious. It comes down to society's choices about human rights, the role of government and free markets, the importance of being "green," and fundamental values. Gleick gets to the heart of the bottled water craze, exploring what it means for us to bottle and sell our most basic necessity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bottled and Sold by Peter H. Gleick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The War on Tap Water

Tap water is poison.

—A flyer touting the stock of a Texas

bottled water company.

bottled water company.

When we’re done, tap water will be relegated to showers and washing dishes.

—Susan Wellington, president of the Quaker Oats

Company’s United States beverage division.

Company’s United States beverage division.

SEPTEMBER 15, 2007, was a big day for the alumni, family, and fans of the University of Central Florida and the UCF Knights football team. After years of waiting and hoping, the University of Central Florida had finally built their own football stadium—the new Bright House Networks arena. Under clear skies, and with temperatures nearing 100 degrees, a sell-out crowd of 45,622 was on hand to watch the first-ever real UCF home game against the Texas Long-horns, a national powerhouse. “I never thought we’d see this, but we sure are proud to have a stadium on campus,” said UCF alumnus and Knight fan Tim Ball as he and his family tailgated in the parking lot before the game. And in an exciting, three-hour back-and-forth contest, the UCF Knights almost pulled off an upset before losing in the final minutes 35 to 32.

Knight supporters were thrilled and left thirsting for more—literally. Fans found out the hard way that their new $54-million stadium had been built without a single drinking water fountain. And for “security” reasons, no one could bring water into the stadium. The only water available for overheated fans was $3 bottled water from the concessionaires or water from the bathroom taps, and long before the end of the game, the concessionaires had run out of bottled water. Eighteen people were taken to local hospitals and sixty more were treated by campus medical personnel for heat-related illnesses. The 2004 Florida building code, in effect in 2005 when the UCF Board of Trustees approved the stadium design, mandated that stadiums and other public arenas have a water fountain for every 1,000 seats, or half that number if “bottled water dispensers” are available.1 Under these requirements, the arena should have been built with at least twenty water fountains. Furthermore, a spokesman for the International Code Council in Washington, which developed Florida’s building code, said, “Selling bottled water out of a concession stand is not what the code meant.”

The initial reaction from the University was swift and remarkably unapologetic: UCF spokesman Grant Heston appeared on the local TV news to argue that the codes in place when the stadium was designed didn’t require fountains. A few days after the game, as news of the hospitalizations was reverberating, University President John Hitt said, “We will look at adding the water fountains, but I have to say to you I don’t think that’s the answer to this problem. We could have had 50 water fountains and still had a problem on Saturday.”2 Al Harms, UCF’s vice president for strategic planning and the coordinator for the operations of the stadium, told the Orlando Sentinel, “We won’t make a snap decision” about installing fountains in the new stadium. Harms did promise that they would triple the amount of bottled water available for sale, and give away one free bottle per person at the next game.3 Harms also said, apparently without a trace of sarcasm, “It’s our way of saying we’re sorry.”

For some UCF students, this wasn’t enough. One of them, Nathaniel Dorn, mobilized in twenty-first-century fashion. He created a Facebook group, Knights for Free Water, which quickly attracted nearly 700 members. He and several other students showed up at a packed school hearing, talked to local TV and print media, and ridiculed the school’s offer of a free bottle of water. Under this glare of attention the University did an abrupt about-face and announced that ten fountains would be installed by the next game and fifty would be installed permanently.

All of a sudden public water fountains have vanished and bottled water is everywhere: in every convenience store, beverage cooler, and vending machine. In student backpacks, airplane beverage carts, and all of my hotel rooms. At every conference and meeting I go to. On restaurant menus and school lunch counters. In early 2007, as I waited for a meeting in Silicon Valley, I watched a steady stream of young employees pass by on their way to or from buildings on the Google campus. Nearly all were carrying two items: a laptop and a throw-away plastic bottle of water. When I entered the lobby and checked in at reception, I was told to help myself to something to drink from an open cooler containing fruit juices and rows of commercial bottled water. As I walked to my meeting, I passed cases of bottled water being unloaded near the cafeteria.

Water fountains used to be everywhere, but they have slowly disappeared as public water is increasingly pushed out in favor of private control and profit. Water fountains have become an anachronism, or even a liability, a symbol of the days when homes didn’t have taps and bottled water wasn’t available from every convenience store and corner concession stand. In our health-conscious society, we’re afraid that public fountains, and our tap water in general, are sources of contamination and contagion. It used to be the exact opposite—in the 1800s, when our cities lacked widespread access to safe water, there were major movements to build free public water fountains throughout America and Europe.

In London in the mid-1800s, water was beginning to be piped directly into the homes of the city’s wealthier inhabitants. The poor, however, relied on private water vendors and neighborhood wells that were often broken or tainted by contamination and disease, like the famous Broad Street pump that spread cholera throughout its neighborhood. At the time of London’s Great Exhibition in 1851, conceived to showcase the triumphs of British technology, science, and innovation, Punch Magazine wrote: “Whoever can produce in London a glass of water fit to drink will contribute the best and most universally useful article in the whole exhibition.”4 Just three years after the Exhibition, thousands of Londoners would die in the third massive cholera outbreak to hit the city since 1800.

By the middle of the twentieth century, spectacular efforts to improve water-quality treatment and major investments in modern drinking-water systems had almost completely eliminated the risks of unsafe water. Those of us who have the good fortune to live in the industrialized world now take safe drinking water entirely for granted. We turn on a faucet and out comes safe, often free fresh water. Notwithstanding the UCF stadium fiasco, we’re rarely more than a few feet from potable water no matter where we are. But those efforts and investments are in danger of being wasted, and the public benefit of safe tap water lost, in favor of private gain in the form of little plastic water bottles.

The growth of the bottled water industry is a story about twenty-first-century controversies and contradictions: poverty versus glitterati; perception versus reality; private gain versus public loss. Today people visit luxury water “bars” stocked with bottles of water shipped in from every corner of the world. Water “sommeliers” at fancy restaurants push premium bottled water to satisfy demand and boost profits. Airport travelers have no choice but to buy bottled water at exorbitant prices because their own personal water is considered a security risk. Celebrities tout their current favorite brands of bottled water to fans. People with too much money and too little sense pay $50 or more for plain water in a fancy glass bottle covered in fake gems, or for “premium” water supposedly bottled in some exotic place or treated with some magical process.

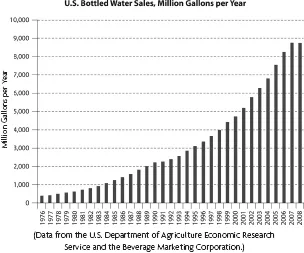

In its modern form, bottled water is a new phenomenon, growing from a niche mineral-water product with a few wealthy customers to a global commodity found almost everywhere. The recent expansion of bottled water sales has been extraordinary. In the late 1970s, around 350 million gallons of bottled water were sold in the United States—almost entirely sparkling mineral water and large bottles to supply office water coolers—or little more than a gallon and a half per person per year. As the figure below shows, between 1976 and 2008, sales of bottled water in the United States doubled, doubled again, doubled again, and then doubled again. In 2008, nearly 9 billion gallons (over 34 billion liters) of bottled water were packaged and sold in the United States and five times this amount was sold around the world, feeding a global business of water providers, bottlers, truckers, and retailers at a cost to consumers of over a hundred billion dollars.

Americans now drink more bottled water than milk or beer—in fact, the average American is now drinking around 30 gallons, or 115 liters, of bottled water each year, most of it from single-serving plastic containers. Bottled water has become so ubiquitous that it’s hard to remember that it hasn’t always been here. As I write this sentence I’m sitting in the café in the basement of the capitol building in Sacramento, California, and all I have to do is lift my eyes from my computer screen—right in front of me are vending machines selling both Dasani and Aquafina. Yet, like UCF football fans, I can’t tell you where the nearest water fountain is.

Millions of Americans still drink tap water at home and in restaurants. But there is a war on for the hearts, minds, and pocket-books of tap water drinkers, a huge market that water bottlers cannot afford to ignore. The war on the tap is an undeclared war, for the most part, but in recent years, more and more subtle (and not so subtle) campaigns that play up the supposed health risks of tap water, or the supposed health advantages of bottled water, have been launched by private water bottlers.

How do you convince consumers to buy something that is essentially the same as a far cheaper and more easily accessible alternative? You promote perceived advantages of your product, and you emphasize the flaws in your competitor’s product. For water bottlers this means selling safety, style, and convenience, and playing on consumer’s fears. Fear is an effective tool. Especially fear of sickness and of invisible contamination. If we can be made to fear our tap water, the market for bottled water skyrockets.

I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised, therefore, when I opened my mailbox and found a flyer with a cover image of a goldfish swimming in a glass of drinking water. “There is something in this glass you do not want to drink. And it’s not the fish,” shouted the bold and colorful text in the mailer, offering me home delivery of bottles of Calistoga Mountain Spring Water. “How can you be sure your water is safe? Take a closer look at the water in our glass. Can you tell if it’s pure? Unfortunately, you can’t.” And the solution offered? The “Path to Purity” lies with bottles of water, delivered to your door by truck, under a monthly contract.

“Tap water is poison!” declares another flyer my neighbor Roy received in the mail in early 2007 touting the stock of Royal Spring Water Inc., a Texas bottled water company. “Americans no longer trust their tap water…. Clearly, people are more worried than ever about what comes out of their taps.” Roy, a thoughtful guy, told me he was actually more worried about what came out of his mailbox than his tap. The website of another bottler says, “Tap water can be inconsistent…. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has reported that hundreds of tap water sources have failed to meet minimum standards.”5

These attacks could be dismissed as the inappropriate actions of a few small players, except that some of the world’s biggest bottlers have also targeted tap water. In 2000, shortly before he was made chairman of Pepsi Co’s North American Beverage and Food division, Robert S. Morrison publicly declared, “The biggest enemy is tap water…. We’re not against water—it just has its place. We think it’s good for irrigation and cooking.”6 That same year, Susan Wellington, president of the Quaker Oats Company’s United States beverage division, candidly told industry analysts, “When we’re done, tap water will be relegated to showers and washing dishes.”7 “We need to change the way we sell water,” said industry analyst Kathleen Ransome at the 2006 International Bottled Water Association annual convention in Las Vegas. “At what point will consumers turn to the tap?”8

Subtler advertising approaches also play on our fears. Pepsi Co hired actress Lisa Kudrow to promote Aquafina with the phrase “So pure, we promise nothing” in a campaign Brandweek magazine jokingly called the “Nothing” campaign.9 Kinley in India offers “Trust in every drop,” while another Indian bottler, Bisleri, advertises “Bisleri. Play safe.”

Officially, the large bottled water industry associations advise their members to refrain from attacks on tap water. Some bottled water companies have signed up to the International Bottled Water Association’s voluntary code of advertising, “which encourages members not to disparage tap water.”10 Alas, as Captain Barbossa notes in the popular movie Pirates of the Caribbean, “the code is more what you’d call ‘guidelines’ than actual rules,” and even the bottled water associations cannot resist making critical comments about tap water. “The difference between bottled water and tap water is that bottled water’s quality is consistent,” said Stephen Kay, IBWA spokesman in May 2001, implying, of course, that tap water quality isn’t and thus worse.11 In 2002, Kay said, “Some people in their municipal markets have the luxury of good water. Others do not.”12 Similarly, the website of the Australasian Bottled Water Association pokes barbs at tap water, saying, “Some people also wish to avoid certain chemicals used in the treatment of public water supplies, such as chlorine and fluoride, and are therefore turning to the chemical-free alternative.”13

In the fall of 2007 I attended the IBWA annual convention in Las Vegas. Las Vegas is a pretty incongruous place to hold a bottled water convention. Planted in the heart of one of the driest regions in the United States, it has very limited access to water. Yet the IBWA’s major social event is a golf tournament played on water-intensive grass that consumes precious, limited water. The bottled water convention itself is a cross between a pep rally, a political campaign meeting, and a how-to seminar for individuals hoping to cash in on the bottled water craze. I wandered from session to session, from discussions of marketing strategies to closed-door meetings on how to deal with new regulatory efforts by federal agencies. I listened to talks on how to counter the efforts of anti-bottled water activists and watched demonstrations of the latest machines for bottling water. The culmination of the convention was the keynote presentation of Fred Smith, president of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, which promotes a libertarian, free-market agenda.14 Smith extolled the virtues of a world where business entrepreneurs could make money selling water in bottles. The problem, Smith told me afterward, without a hint of irony, was that water “suffers most from being treated as a common property resource.” Smith believes that “water policy could benefit greatly from exploring the strategies that have been used to produce oil.”15

It is this belief that water is fundamentally no different than oil or any other private commodity that lies at the heart of the controversy over selling water. A few months after the IBWA convention, Smith’s Competitive Enterprise Institute launched a special project called “Enjoy Bottled Water” in which they criticize the safety of tap water, ridicule opponents of bottled water, and promote the industry’s merits. “Bottled water is substantially different from ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 - The War on Tap Water

- Chapter 2 - Fear of the Tap

- Chapter 3 - Selling Unwholesome Provisions

- Chapter 4 - If It’s Called “Arctic Spring,” Why Is It from Florida?

- Chapter 5 - The Cachet of Spring Water

- Chapter 6 - The Taste of Water

- Chapter 7 - The Hidden Cost of Convenience

- Chapter 8 - Selling Bottled Water: The Modern Medicine Show

- Chapter 9 - Drinking Bottled Water: Sin or Salvation?

- Chapter 10 - Revolt: The Growing Campaign Against Bottled Water

- Chapter 11 - Green Water? The Effort to Produce Ethical Bottled Water

- Chapter 12 - The Future of Water

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index