![]()

Chapter 1

Transportation and Sustainability in Campus Communities

The historic or traditional American college campus was designed around the pedestrian, and walking was the primary transportation mode for most students. Up until the 1940s most students lived on campus and arrived by bus, train, or trolley.

In the earliest years of many colleges and universities, the first buildings were located just beyond the bustling commercial center of the “host” town or city. The institutions of higher learning were often separated from the town by woods, a stream, a meadow, or some natural buffer. Among thousands of examples we could cite are Colgate University (1819) at the southern edge of Hamilton, New York, or Beloit College (1846) up on the hill above the Rock River and above downtown Beloit, Wisconsin. Old Main is the original University of Colorado (1876) edifice and it was situated several blocks south of Boulder Creek and on a predominant hill overlooking downtown Boulder, Colorado. Western Washington State University’s picturesque campus (1933) began somewhat isolated from and to the south of Bellingham, Washington. Today most of these schools and thousands of other campuses are surrounded by urban development. In some cases—such as the University of Chicago, Carnegie Mellon, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, San Jose State University, Wayne State University, or Georgetown University—not only has there been an “engulfment” of urbanization but also there have been substantial increases of population density in close proximity to the typical urban campus. These two forces, the urban swallowing of the campus and the densification of the contiguous neighborhoods, set the stage for land-use problems. Many school administrators believe the institution needs to grow in order to survive or stay competitive with other schools while the town struggles with added housing demands and traffic congestion and overspill into the community (Gurwitt 2003).

1.1

In 1927, students at the University of Michigan mourn a proposed ban on the auto in this cartoon.

Courtesy of University of Michigan, Bentley Library

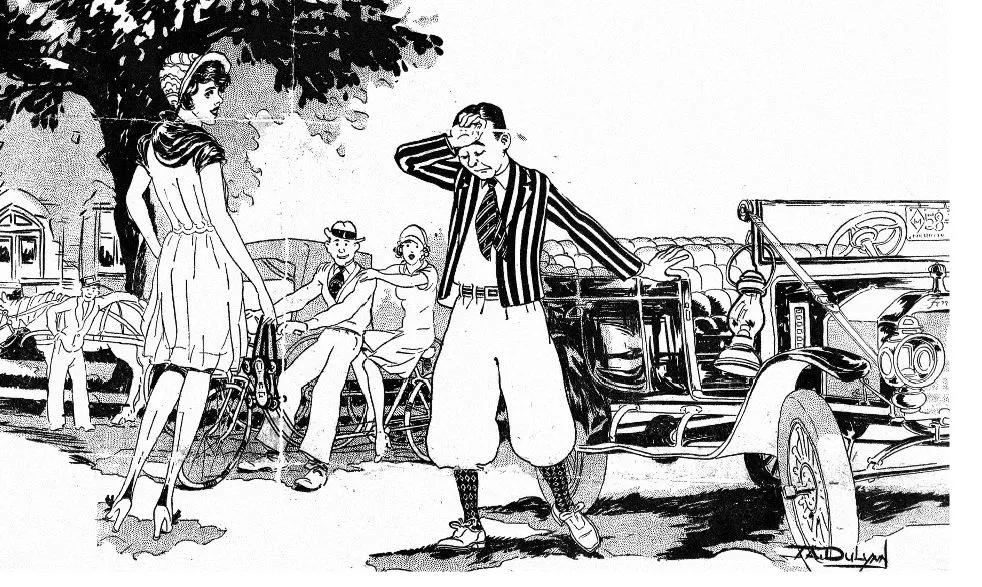

1.2

Michigan’s central campus mall near Burton Tower had ample parking for few cars in the early 1940s. Courtesy of University of Michigan, Bentley Library

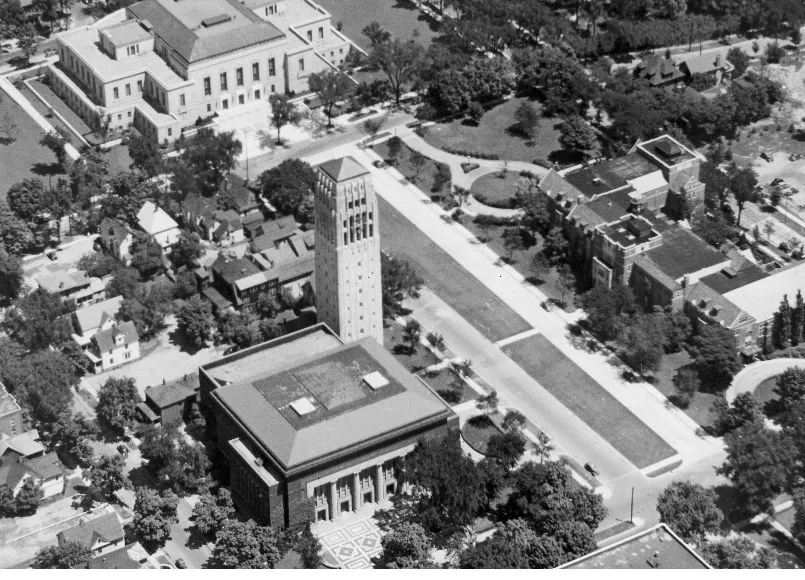

1.3

The Michigan campus mall shows the increase in cars after World War II.

Courtesy of University of Michigan, Bentley Library

1.4

In 2003, the mall between Rackham and the Michigan library on the University of Michigan campus gives priority to pedestrians.

Photo by Val Havlick

1.5

The cost of adding parking by building structures can exceed $30,000 per net new space.

Photo by Francoise Poinsatte

The University of Michigan demonstrates a typical transformation from a pedestrian-oriented campus plan to one that became saturated with automobile trips. From the 1880s until 1920, the landscaped corridor of the central campus was a pedestrian place. In the 1930s and 1940s parking for the infrequent automobile was provided. In the period between 1960 and 1990 the once peaceful strolling mall was modified to accommodate car parking. In recent years some car parking has been eliminated and replaced by flower gardens and seating for students and visitors.

The number of students who own cars has increased over time. Today there is a common and rather widespread problem of automobile overspill beyond campus parking facilities onto the neighborhoods surrounding the campus. In many communities, housing in close proximity to a campus has become a premium. As student-housing scarcity occurs, middle- and low-income students resort to housing that is farther from campus and somewhat more affordable. This tends to increase automobile travel. As campus parking facilities fill each day, and as parking rates rise, student car commuters search for parking in neighborhoods already heavily populated by students—most of whom have a car and have used the public and private car parking areas for their auto storage needs.

Short-term car parking, with a car space “turning over” four to six times a day, tends to change the livability of a neighborhood by increasing the noise, litter, vandalism, and general degradation of the residential environment that come from the increased number of student vehicles. The car storage overspill is a documented nuisance, and blight has now become a trademark of most large university neighborhoods where student enrollment outpaces the town’s ability to absorb the greater number of cars that are brought to school by increasing numbers of students.

We have contacted 150 campus planners and parking management officials at university and college campuses around the country. (Please see the Appendix for a list of respondents and institutions contacted.) In our survey of nearly 8 percent of the 3,300 colleges and universities, only six reported that they had no parking problems on campus or in nearby university neighborhoods. The University of North Carolina–Charlotte reported they have 2,000 empty car spaces per day and Warren Wilson College in Asheville told our research team that “they have more spaces than cars.” No freshman cars are permitted at Warren Wilson (on the basis of educational priorities), which has 800 students and 375 faculty and staff. This is certainly the exception rather than the rule in our survey of colleges and universities. The overwhelming number of responding schools report “severe to critical” parking overspills into their communities. It should be no surprise when the average student-staff-faculty population ratio to available car parking spaces is approximately 4:1, according to our study of institutions of higher education.

There are at least three schools of thought on how the student auto overabundance can be managed. One approach is to increase the supply of car storage and parking areas (University of Arizona Parking and Transportation Services 2003). The costs of this approach vary from city to city and campus to campus. A second position is for the academic institution to rely on the free market system to meet increasing demand. This approach is where the institution relies on private facilities and outside parking providers. Some say this is the status quo, a do-nothing stance. The third technique can be called the demand management approach. Instead of increasing the supply of parking the university would explore ways in which the demand for parking could be reduced (Shoup 1997).

1.6

The University of California–Santa Cruz provides an example of a comprehensive demand management approach to campus transportation. The campus provides a bike trailer and van to assist bike commuters up steep roads on inbound trips—a unique TDM tool.

Courtesy of University of California–Santa Cruz

Later in the book examples of transportation demand management (TDM) will be discussed in more detail, but it should be noted here that effective parking demand management, which reduces neighborhood overspill, is composed of multiple tools for specific town and campus conditions. The toolkit usually contains specialized parking permits, various forms of bus service and bus shuttles, and differential parking prices related to distance from campus. Other components in a TDM toolkit could include effective bike paths, storage lockers and other biking facilities, and special incentives for vanpool and carpool parking that are “close in.” Some schools are experimenting with free bikes, such as those that are seen scattered around campus at the University of Florida–Gainesville.

No one parking demand management tool works all by itself, nor is one parking reduction plan appropriate for every campus. Each institution and community should craft an array of parking management technologies that fit the needs of the student body and faculty. Campuses that are primarily residential-based have different parking and traffic challenges from a commuter college or junior college, which tend to be more automobile dependent more hours of the day and evening. Universities with a medical center and medical schools as a part of their central campus have different peak demand periods than a liberal arts college with 80 percent or higher residential enrollment.

1.7

Campus shuttle buses reduce the need for student cars on the University of Vermont campus.

Photo by Spenser Havlick

1.8

The SKIP high-frequency bus route serving the University of Colorado area carries three times as many people as the more traditional route it replaced.

Photo by Spenser Havlick

Factors That Influence Campus Transportation Policies

There are seven major factors that influence the transportation policy and practices on university and college campuses. These factors play different roles of importance at different educational institutions, but they are all at work to one degree or another.

BOX 1.1

TRAVEL DEMAND MANAGEMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA–SANTA CRUZ

Wes Scott, director of Transportation and Parking Services (TAPS) at the University of California–Santa Cruz, has become a champion of traffic demand management (TDM) practices. The Santa Cruz campus is nestled amidst a redwood forest with a campus population of 17,000, but with only 5,000 parking spaces. Scott has implemented an array of TDM practices as an alternative to cutting down redwoods for car lots and as an economically wise decision.

The UC–Santa Cruz TDM tools include carpools that carry 300 people per day, vanpools transporting 100 per day, a transit pass system that moves 525 students each day, and a differential pricing system for parking permits. The TAPS parking permit for close-in parking costs $684 per year and the remote lots cost $384 annually. Freshmen and sophomores are not permitted to have cars on campus. Scott reports, “We stack vehicles in the aisles of remote parking lots and have created 4...