eBook - ePub

Beyond Mobility

Planning Cities for People and Places

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Cities across the globe have been designed with a primary goal of moving people around quickly—and the costs are becoming ever more apparent. The consequences are measured in smoggy air basins, sprawling suburbs, unsafe pedestrian environments, and despite hundreds of billions of dollars in investments, a failure to stem traffic congestion. Every year our current transportation paradigm generates more than 1.25 million fatalities directly through traffic collisions. Worldwide, 3.2 million people died prematurely in 2010 because of air pollution, four times as many as a decade earlier. Instead of planning primarily for mobility, our cities should focus on the safety, health, and access of the people in them.

Beyond Mobility is about prioritizing the needs and aspirations of people and the creation of great places. This is as important, if not more important, than expediting movement. A stronger focus on accessibility and place creates better communities, environments, and economies. Rethinking how projects are planned and designed in cities and suburbs needs to occur at multiple geographic scales, from micro-designs (such as parklets), corridors (such as road-diets), and city-regions (such as an urban growth boundary). It can involve both software (a shift in policy) and hardware (a physical transformation). Moving beyond mobility must also be socially inclusive, a significant challenge in light of the price increases that typically result from creating higher quality urban spaces.

There are many examples of communities across the globe working to create a seamless fit between transit and surrounding land uses, retrofit car-oriented suburbs, reclaim surplus or dangerous roadways for other activities, and revitalize neglected urban spaces like abandoned railways in urban centers.

The authors draw on experiences and data from a range of cities and countries around the globe in making the case for moving beyond mobility. Throughout the book, they provide an optimistic outlook about the potential to transform places for the better. Beyond Mobility celebrates the growing demand for a shift in global thinking around place and mobility in creating better communities, environments, and economies.

Beyond Mobility is about prioritizing the needs and aspirations of people and the creation of great places. This is as important, if not more important, than expediting movement. A stronger focus on accessibility and place creates better communities, environments, and economies. Rethinking how projects are planned and designed in cities and suburbs needs to occur at multiple geographic scales, from micro-designs (such as parklets), corridors (such as road-diets), and city-regions (such as an urban growth boundary). It can involve both software (a shift in policy) and hardware (a physical transformation). Moving beyond mobility must also be socially inclusive, a significant challenge in light of the price increases that typically result from creating higher quality urban spaces.

There are many examples of communities across the globe working to create a seamless fit between transit and surrounding land uses, retrofit car-oriented suburbs, reclaim surplus or dangerous roadways for other activities, and revitalize neglected urban spaces like abandoned railways in urban centers.

The authors draw on experiences and data from a range of cities and countries around the globe in making the case for moving beyond mobility. Throughout the book, they provide an optimistic outlook about the potential to transform places for the better. Beyond Mobility celebrates the growing demand for a shift in global thinking around place and mobility in creating better communities, environments, and economies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond Mobility by Robert Cervero,Erick Guerra,Stefan Al in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Urban Recalibration

Beyond Mobility is about reordering priorities. In the planning and design of cities, far more attention must go toward serving the needs and aspirations of people and the creation of great places as opposed to expediting movement. Historically it has been the opposite. In the United States and increasingly elsewhere, investments in motorways and underground rail systems have been first and foremost about moving people between point A and point B as quickly and safely as possible. On the surface, of course, this is desirable. However, the cumulative consequences of this nearly singular focus on expeditious movement have revealed themselves with passage of time, measured in smoggy air basins, sprawling suburbs, and—despite hundreds of billions of dollars in investments—a failure to stem traffic congestion, to name a few. An urban recalibration is in order, we argue, one that follows a more people- and place-focused approach to city building.

Recalibration is a term found in handbooks for precision instruments and flight manuals. It has resonance in city planning circles as well. The roads, subdivisions, and utility corridors that give shape to cities were calibrated from engineering and design manuals with noble aims, such as minimizing accident risks and accommodating the turning radii of eight-wheel fire trucks, but with little attention to unintended consequences. Mobility and public safety are important, but so are clean air and walkable streets. Moreover, traffic engineers have long gauged performance in terms of throughputs of motorized vehicles, not people. The consequence: a vicious cycle of road expansions to accommodate car traffic rather than channeling more resources into modes that are efficient users of road space, such as public transit and cycling. Over the twentieth century, street widths and parking standards continually increased, taking up the majority of public space to accommodate cars.1 In some cities, parking lots alone account for more than a third of the metropolitan footprint.2 The approaches, metrics, and standards used to design cities, we believe, are in serious need of recalibration—not necessarily a seismic shift but rather a rebalancing of priorities that gives at least as much urban planning and community design attention to serving people and places as to mobility. Beyond Mobility charts a pathway for doing so.

The call for urban recalibration and reframing the role of mobility in cities finds its roots in the derived nature of most travel. People drive cars and take trains to go places. It is the makeup and quality of these places and the social and economic interactions they spawn that we value most, more so than the physical act of getting there. As Amory Lovins has said of the energy sector, people don’t care about kilowatts; they care about hot showers, cold beer, and lit rooms. Similarly, people travel to reach jobs, friends, sports arenas, and the like. They seek social and economic interaction, not movement. To the degree that distance is a barrier to interaction, time spent moving over space is time that can often be better spent doing other things (socializing with friends, reading a magazine at the local café, or even logging in more hours—and presumably making more money—at the workplace). Transportation, then, is a means to an end, a vehicle for achieving something else. It is mostly secondary to a larger purpose.

An apt analogy on getting the priorities right is the design of a house. Think of “place” as the house and “transportation” as its utilities. In conceptualizing and planning a house, prospective homeowners dwell on what matters most to them: the layout, floor-plan, architectural styles, kitchen designs, views, and so on. They don’t initially focus on the utilities of a house—the plumbing, wiring, conduits, and pipes—and then design the house around them. The same should hold when scaling up to a neighborhood or city. Recalibrating the planning and design of cities, then, is about lifting the priority given to place vis-à-vis mobility.

In emphasizing mobility, twentieth-century transportation infrastructure has often had harmful effects on people and places. Dangerous and difficult-to-cross intersections and multilane roads have hindered people’s ability to move freely and children’s opportunities to play. Although transportation investments have connected people on a regional level, they have also uprooted communities and lowered home values, epitomized by highways cutting through American neighborhoods in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1953, local residents fiercely protested Robert Moses’s planned six-lane Cross Bronx Expressway, calling it the “Heartbreak Highway,” but to no avail. Moses’s plan was approved and built quickly, bulldozing homes in densely populated neighborhoods in the Bronx, lowering property values, and severing neighborhoods. The Cross Bronx Expressway was but one of the many destructive urban highways built over the ensuing two decades, often with the federal government footing 90 percent of the bill.

Giving stronger priority to place is another way of saying cities should be highly accessible. Accessibility is about the ease of reaching places where people want to go. Cities can become more accessible by increasing mobility (the speed of getting between point A and B), proximity (bringing point A and B closer together), or some combination thereof. Focusing on accessibility and, relatedly, places leads to an entirely different framework for planning and designing cities and their transportation infrastructure. Rather than laying more and more asphalt to connect people with places, activities (e.g., homes, businesses, and shops) might instead be sited closer to each other. A vast body of research shows that the resulting mixed land use patterns can shorten distances and invite more leisurely paced, pollution-free travel. It’s been said that planning for the automobile city focuses on saving time. Planning for the accessible city focuses on time well spent.

As discussed in this book’s second chapter, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods also build social capital and instill a sense of safety through natural surveillance. For more and more urban dwellers, such neighborhood attributes are every bit as, if not more, important than travel speeds. A principal aim of Beyond Mobility, then, is to provide a framework for designing cities and siting activities so that urban places become more accessible and, as a result, allow more interaction of all types. Such transformative places include regenerated former industrial sites (chapter 5), business parks converted to mixed-use activity centers (chapter 6), walkable neighborhoods huddled around transit stops (chapter 7), and former traffic arteries that now accommodate pedestrians, cyclists, and an active street life (chapter 8).

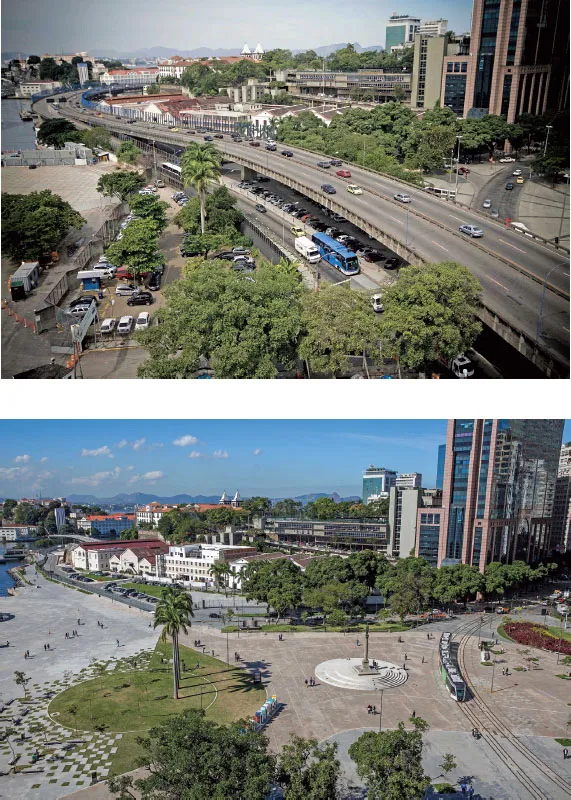

The book’s cover portrays the kinds of physical transformations that are possible by redesigning cityscapes and moving beyond mobility. The cover photo shows an electric tram in Rio de Janeiro’s Porto Maravilha area, sharing a street with pedestrians and flanked by a bright mural that adds color and art to what was once a blank and monotonous warehouse wall. Porto Maravilha is a product of the city’s decision to tear down an imposing viaduct that separated downtown Rio from its waterfront, replaced by a tramway, pedestrian plaza, streetscape improvements, and museum, all in time for the 2016 Summer Olympics. Before-and-after images depict the transformation of this valuable yet long-neglected coastal real estate, from a conduit for swiftly moving trucks and cars to a people-oriented place served by a tram, with a strong accent on aesthetics, amenities, and place-making (figure 1–1). Income from increases in permissible commercial densities and land price appreciations helped finance the project, although it, like other high-ticket Olympic-driven public expenditures in a city with high poverty rates, sparked massive public protests for being pro-rich and anti-poor. Recalibrating cities to focus more on people and places must weigh social consequences. Actions must be socially inclusive, a significant challenge in light of the price increases that typically result from creating higher-quality urban spaces. Strategies for overcoming such challenges are discussed in this book’s concluding chapter.

Figure 1–1. Urban recalibration in Rio de Janeiro: Porto Maravilha project. (top) A former elevated freeway hugging Rio’s waterfront was replaced by (bottom) a tramway, pedestrian plaza, and contemporary museum. (Photos by Companhia de Desenvolvimento Urbano da Região do Porto do Rio de Janeiro [Cdurp].)

Another example of urban recalibration is London’s congestion pricing scheme, in this case reflecting a shift in policy (i.e., software) more than, as in the case of Rio, a physical (i.e., hardware) transformation. London introduced congestion charges in early 2003, building on Singapore’s success with charging motorist fees for entering a cordoned central-city area in peak periods. The first 5 years of congestion charging were matched by, as proponents promised, faster driving speeds for those willing to pay tolls. By late 2008, however, speeds began to fall to their precongestion pricing levels. This creep back was due in part to the taking of some 20 percent of central London’s road space for buses, pedestrians, and cyclists. In her study of London’s charging scheme, Andrea Broaddus notes, “Traffic engineers had whittled away at the road capacity released by congestion charging until it amounted to a significant ‘capacity grab’ of road space and travel time savings away from drivers and toward bus riders, pedestrians, and cyclists.”3 Yet the populace continued to accept congestion charges. Londoners conceded private car mobility in return for what many perceived to be a better living environment: cleaner air, fewer accidents, more space for pedestrians, and a more bike-friendly urban milieu. Central London’s reordering of priorities is evident even at the microscopic intersection level. Besides space, another constrained resource in the urban transportation sector, traffic signal times, was reallocated to nonmotorists. “Reduced waiting time for pedestrians,” Broaddus writes, “meant longer waiting times for motorized traffic, in effect a redistribution of time away from motorized traffic toward pedestrians.”4 In London’s case, the core of the city was recalibrated, reflected by reassignment of road space and reallotments of signal timings, to focus more on people and places and less on private vehicle movements.

Challenges to Creating Sustainable and Just Cities

Cities are the social, cultural, and economic hubs of human activity—“our greatest achievement” in the words of Ed Glaeser in the Triumph of the City.5 They have been fundamental to nearly all human advances in historical memory, from the birth of modern philosophy in Athens and the Renaissance in Florence to the automotive industry in Detroit and the digital revolution in Silicon Valley.6 Thus cities create wealth. Today, the world’s 600 largest cities, representing a fifth of the world’s population, generate 60 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP).7 Cities are also home to the majority of the world’s population and ground zero of global population growth. The United Nations estimates that the planet will add another 1.5 billion urban residents to cities over the next 20 years.8 That is the equivalent to adding eight megacities (i.e., eight Jakartas, Lagoses, or Rio de Janeiros) every year over the next two decades, a daunting challenge to say the least. How these cities grow will be fundamental to human health, wealth, and happiness.

If well designed, cities are also the greenest places on Earth. Manhattanites consume carbon at the level that the rest of the United States did in the 1920s.9 Many walk or take transit to get about Manhattan and its surroundings, consuming one-tenth the petroleum of the typical American. However, not all cities are well designed, and indeed few are as transit and pedestrian friendly as New York. Consequently, the world’s cities have oversized, disproportionate environmental footprints. With more than 50 percent of the world’s population, cities account for 60 to 80 percent of the world’s energy consumption and generate as much as 70 percent of the human-induced greenhouse gas emissions, primarily through the consumption of fossil fuels for energy supply and transportation.10 Cities are also highly vulnerable to the ill effects of climate change, especially coastal cities of the Global South that risk inundation from rising sea levels.

Cities unfortunately also suffer from extreme poverty and deprivation. Some 900 million people—a third of the world’s urban population—today live in slums.11 In sub-Saharan Africa, slum dwellers make up nearly three-quarters of the urban population.12 The World Bank estimated that, in 2002, three-quarters of a billion city dwellers lived on less than US$2 per day worldwide, a number that has surely grown.13 Moreover, today some 250 million urban dwellers have no electricity.14 And every year, more than 800,000 deaths occur worldwide due to poor sanitation, with the share in cities rising as urban growth outpaces the corresponding expansion of sewage and piped water facilities.15 All this underscores the importance of ensuring that the rewards from recalibrating the planning and design of cities do not accrue just to well-off classes. To gain legitimacy, not to mention political traction and social acceptance, actions must be pro-poor, at some level helping to alleviate urban poverty and improve living conditions.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of accessibility in making urban living more affordable and socially just. Across the globe, urban residents typically spend more on housing and transportation than all other goods combined.16 Poor access drains the few resources the poor have at their disposal. In Mexico City, the poorest fifth of households spend about a quarter of their income on public transit.17 Those on the periphery face daunting commutes that last an average of 1 hour and 20 minutes in each direction. In the United States, where transit supply is sparse in most neighborhoods, limited accessibility prevents many low-income people from finding work, reaching medical services, or shopping at well-stocked supermarkets.

From a fiscal perspective, governments pour substantial resources into transportation investments and foot a big portion of the bill for mobility-oriented planning practices, particularly sprawl and the public health impacts of pollution and traffic collisions. In the United States, at the close of the twentieth century, the cost of providing infrastructure and services in sprawling, car-oriented developments—excluding external social costs—was nearly $30,000 more per housing unit than in compact developments.18 Added to this are the less visible yet prevalent costs of auto-oriented living, including physical inactivity, traffic fatalities, and deteriorating air quality, costs that at some level the public sector has to spend resources to try to offset.19

Despite the importance of cities and their inhabitants, too often the form, shape, and even culture of cities have become the unintended consequence of policies and investments to improve mobility. Truly transportation has become the tail that wags the dog. Putting people and place back at the center of how and why we invest in urban transportation is essential to improving humanity’s overall social, environmental, and economic well-being in the twenty-first century.

The Case for Moving Beyond Mobility

As outline above, the costs of designing cities around movement are becoming ever more apparent. So too are the opportunities to shift our dominant transportation paradigm to focus investments on creating vibrant and livable cities with neighborhoods that cater to their residents, not just their residents’ movement. In making this case, we draw on experiences and statistics from a range of cities and countries in Europe, North America, Asia, and to a lesser extent Africa throughout the book. Some of the figures—though well known in the fields of public health and transportation planning—are shocking. Every year our current transportation paradigm generates more than 1.25 million fatalities directly through traffic collisions and contributes to billions of lost years of life from local pollution. Worldwide, 3.2 million people died prematurely in 2010 because of air pollution, four times as many as a decade earlier.20

The reordering of transportation planning priorities is but part of the motivation behind Beyond Mobility. A stronger focus on access...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Urban Recalibration

- Part One: Making the Case

- Part Two: Contexts and Cases

- Part Three: Looking Forward

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index