eBook - ePub

World Agriculture and the Environment

A Commodity-By-Commodity Guide To Impacts And Practices

- 570 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Agriculture and the Environment

A Commodity-By-Commodity Guide To Impacts And Practices

About this book

World Agriculture and the Environment presents a unique assessment of agricultural commodity production and the environmental problems it causes, along with prescriptions for increasing efficiency and reducing damage to natural systems. Drawing on his extensive travel and research in agricultural regions around the world, and employing statistics from a range of authoritative sources including the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, the author examines twenty of the world's major crops, including beef, coffee, corn, rice, rubber, shrimp, sorghum, tea, and tobacco. For each crop, he offers comparative information including:

• a "fast facts" overview section that summarizes key data for the crop

• main producing and consuming countries

• main types of production

• market trend information and market chain analyses

• major environmental impacts

• management strategies and best practices

• key contacts and references

With maps of major commodity production areas worldwide, the book represents the first truly global portrait of agricultural production patterns and environmental impacts.• main producing and consuming countries

• main types of production

• market trend information and market chain analyses

• major environmental impacts

• management strategies and best practices

• key contacts and references

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Agriculture and the Environment by Jason Clay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Agribusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

C0MMODITIES

3

COFFEE

COFFEE Coffea arabica, C. canephora, and other species

Source: FAO 2002. All data for 2000.

Area in Production (Mha)

OVERVIEW

The coffee plant was originally found and cultivated by the Oromo people in the Kafa province of Ethiopia, from which it received its name. Around 1000 A.D., Arab traders took coffee seeds home and started the first coffee plantations. The first known coffee shop was opened in Constantinople in 1475, and the idea quickly spread to other parts of Europe. England’s King Charles II raged against coffeehouses as centers of sedition because they were the meeting place of writers and businessmen. Lloyd’s insurance company was started in the back room of a coffeehouse in 1689. In fact, coffee shops became centers of political and religious debate throughout the continent, and many were subsequently closed. The owners were often tortured.

Coffee first arrived in Europe from Turkey via overland trade routes. It is not known exactly when coffee first arrived, but it had probably been there some time before coffeehouses became common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is possible that coffee was brought in along the same trade routes that were used to transport gold, valuable gums, and ivory from Africa and silk and spices from Asia. In any case, coffeehouses were already established in northern Europe with the sixteenth-century arrival of cocoa, which then spread quickly as another coffeehouse drink.

Over the centuries coffee has gone from a luxury to necessity. Globally, coffee consumption is increasing but not nearly as rapidly as production, so prices are decreasing. In 2002 real coffee prices reached historic lows. Many producers are abandoning coffee plantations; others are destroying them. All of this is happening when markets in developed countries are fixated more than ever on high-quality coffee. While many consumers are willing to pay more for their coffee, they are actually drinking less of it. Furthermore, increased supply has not been followed by a commensurate decrease in price in most developed countries.

PRODUCING COUNTRIES

Coffee is produced in about eighty tropical or subtropical countries. Some 10.6 million hectares are currently in coffee production. Average annual production is about 7.4 million metric tons of green, or unroasted, coffee. The value-added coffee industry is worth about U.S.$60 billion worldwide, making coffee the second most valuable legally traded commodity in the world after petroleum (McEwan and Allgood 2001). It is a primary export of many developing countries, and as many as 25 5 million people depend on coffee for their livelihood.

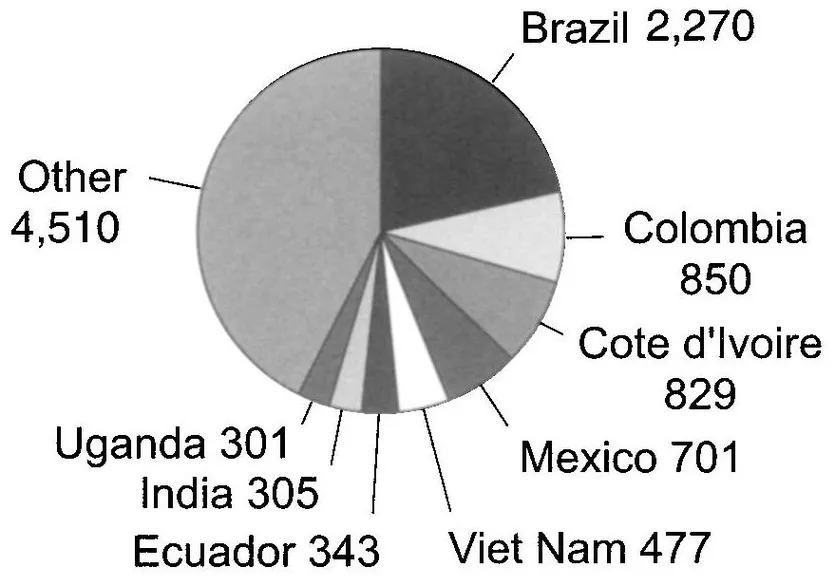

The main coffee-producing countries by area planted, as opposed to total production, are Brazil (2.27 million ha), Colombia (850,000 ha), Cote d’Ivoire (829,000 ha), Mexico (701,326 ha), and Vietnam (477,000 ha). Each of the following countries has between 200,000 and 350,000 hectares planted to coffee: Cameroon, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Peru, Uganda, and Venezuela. Combined, the top eleven countries account for nearly 74 percent of all land devoted to coffee and 74 percent of global production as well (FAO 2002). Even so, coffee production is less concentrated than many other commodities.

Coffee can still be important from an overall point of land use even if the country is not a major exporter. For example, Cote d’Ivoire and Puerto Rico both have 25 to 49 percent of all their agricultural land planted to coffee. Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guinea, Panama, and Papua New Guinea each have 10 to 24 percent of all their agricultural land planted to coffee.

The main coffee producers by volume harvested are Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, Mexico, Cote d’Ivoire, and Guatemala. These countries are also major coffee exporters. However, coffee is also one of the leading exports (see Table 3.1 ) in a number of countries that are not the largest producers or exporters. World exports are expected to rise by 11 percent to 81 million bags in 2002, while stockpiled reserves are expected to reach record levels of 27 million bags.

Globally, production averages 698 kilos per hectare. Martinique has the highest per-hectare production with more than four times the global average. Tonga achieves more than three times the global production average while Costa Rica, Zimbabwe, Thailand, and Malawi all produce at more than double the global average.

CONSUMING COUNTRIES

Coffee began as a luxury item, but it has become a basic food item that is now considered a daily necessity for many consumers. Today more than 2 billion people around the world are estimated to drink coffee regularly. Europe’s thirst for coffee is the most voracious, as it annually consumes 2 million metric tons or just over 40 percent of all coffee traded globally (The Financial Times 2002).

TABLE 3.1. Coffee’s Ranking of Total Exports by Value for Selected Countries, 2001

| Leading Export | Second Largest Export | Third Largest Export |

|---|---|---|

| Burundi | Angola | Costa Rica |

| El Salvador | Colombia | Equatorial Guinea |

| Ethiopia | Kenya | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Guatemala | Laos | |

| Honduras | Sierra Leone | |

| Madagascar | Yemen | |

| Nicaragua | Congo | |

| Rwanda | ||

| Tanzania | ||

| Uganda |

Source: ITC 2002.

Traditionally, producing countries along with the United States and Europe consume the most coffee by far. The United States consumes 25 percent of internationally traded coffee. However, the amount of coffee bought in the United States has declined in both absolute and per capita terms. Consumption throughout the European Union has also declined, but it is rising in Japan and Russia. The main coffee importers, as shown in the Fast Facts chart, are the United States, Germany, Japan, Italy, and France.

More people throughout the world are drinking coffee. Some 40 percent of the world’s population drinks at least one cup of coffee each year. In general consumers first turn to lower-quality robusta varieties, which are used to make instant and mass-market coffee. As markets mature, consumers switch to higher-valued arabica blends, but they do not necessarily drink more coffee.

The industry has its eyes on China as an indicator of future global market trends. The Chinese currently drink about a cup per person per year. If China follows Taiwan, this will increase to thirty-eight cups per year. If it approaches the United States, consumption could reach 463 cups. Sweden has the highest per capita coffee consumption in the world with each person drinking on average 1,100 cups per year. How China progresses will have a tremendous impact on global demand and markets. It is likely, however, that initial impacts will be confined to the lower-grade beans used to make instant coffee.

The trade in coffee is relatively concentrated. In 1989 eight companies controlled more than half of the internationally traded coffee (See Table 3.2). No single company dominates the trade, however. Consolidation of the food industry is likely to affect coffee traders as well.

PRODUCTION SYSTEMS

Coffee is a woody shrub or small tree that can reach 10 meters in height, but under cultivation it is usually pruned to about 2.5 meters to facilitate harvesting. Coffee grows in tropical climates and performs best with good sunshine, moderate rainfall,

TABLE 3.2. The World’s Largest Coffee Traders, 1989

| Enterprise | Volume (1,000 bags) | Market Share |

|---|---|---|

| Rothfos | 9,000 | 12.6% |

| ED & F. Man Holdings Limited | 5,000 | 7.0% |

| Volkart | 4,000 | 5.6% |

| Cargil | 4,000 | 5.6% |

| Aron | 4,000 | 5.6% |

| Rayner | 4,000 | 5.6% |

| Bozzo | 3,500 | 4.9% |

| Sueden | 3,500 | 4.9% |

| Total | 36,500 | 51.1% |

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit 1991.

average temperatures from 15 to 21 degrees Celsius (59 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit), no frost, and at altitudes between sea level and just over 1,800 meters (6,000 feet) (Manion et al. 1999).

Coffee matures (begins to flower and fruit) about three years after planting. One main and one secondary flowering season occur per year. Each mature tree produces approximately 2,000 “cherries” per year or 4,000 beans. This is the equivalent of half a kilogram (1 pound) of roasted coffee (Manion et al. 1999).

Coffee is a relatively easy crop to grow, but it is susceptible to a number of diseases and insect pests. At least 350 different diseases attack coffee, while more than 1,000 species of insects may cause the plant problems.

Two of the most significant factors that affect coffee production in any country are the relative costs of land and labor. Because coffee grown in full sun has a productive life of six to eight years and shade-grown coffee eighteen to twenty-four years (even more if plants are cut back and harvested from the new shoots), the relative value of land and labor can shift over time. Historically, most commercial production came from landholdings of 500 hectares or more. Today holdings of less than 5 hectares of planted coffee account for more than half of global production. Small producers are able to substitute unpaid family labor for both paid outside labor and many of the more expensive chemical inputs.

Two species account for the bulk of the coffee produced around the world—arabica (Coffea arabica) and robusta (C. canephora). Arabica came from the highlands of Ethiopia and was the first type of coffee that was produced for sale. Production of robusta coffee developed after World War II. The two species, and improved varieties developed from them, differ in taste, aroma, caffeine content, disease resistance, and optimum cultivation conditions. Natural variations in soil, sun, moisture, slope, disease, and pest conditions dictate which coffee is most effectively cultivated in which region of the world. The two coffees are compared in Table 3.3. In general, arabica coffee is produced in Latin America while robusta coffee is produced in West Africa and Southeast Asia. However, Brazil is both the world’s largest arabica producer and the second largest (after Vietnam) robusta producer.

TABLE 3.3. Comparison of Arabica and Robusta Coffee Varieties

| Arabica | Robusta | |

|---|---|---|

| Altitude of cultivation | 500-2000 m | 0-1000 m |

| Temperature requirements | Moderate | More heat tolerant |

| More sensitive to cold | ||

| Humidity requirements | Lower | Higher |

| Soil requirements | Fertile soil | Poorer soils |

| Disease resistance | Low | Higher |

| Flavor profile | Fuller flavor | Weaker flavor |

| Caffeine content | Lower | Higher |

| Average price | Higher (up to 30%) | Lower |

| Labor as percentage of total variable costs | 40% | 60% |

| Agrochemical and material inputs as percentage of total variable costs | 25% | 15% |

| Overhead as percentage of total variable costs | 35% | 25% |

| Proportion of world supply | 75% | 25% |

| Main products | High-quality brands and specialty coffees | Instant, flavorings, mass-produced brands |

Source: De Graaf 1986, as cited in Manion et al. 1999.

Note: Overhead includes capita, administration, and management.

In the 1990s there was considerable expansion of coffee production into new areas. The new coffee producers, including Vietnam and India, were able to be competitive in spite of low prices because labor was cheap and they could produce robusta coffee on relatively poor soils. Traditional coffee producers, however, such as Colombia, Costa Rica, and Mexico, were able to maintain coffee production in the face of higher land and labor costs by increasing yields from arabica coffee and by focusing on the small but growing markets for higher quality and certified shade-grown and organic coffee.

In the future coffee production will expand in those areas that have low input costs of production (e.g., inexpensive land and labor) with respect to the price that can be obtained for the coffee. Thus, expansion is certain to happen in India and Vietnam and perhaps in Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia. Future environmental costs of coffee production are likely to be most pronounced in these regions. However, in Costa Rica and Colombia it is unlikely that coffee will hold its own unless a way can be found to certify and market more of it at higher prices so that producers can receive an increasing amount of every dollar paid in consuming countries.

Full-Sun Versus Shade-Grown Coffee

The two main types of coffee production systems are often characterized as “full-sun” and “shade-grown” coffee. Most commodities in the world are produced by genetic varieties that are fairly similar and whose production has very similar methods and environmental costs. This is not the case with coffee. The two main species used for coffee production require different growing conditions.

Full-sun coffee, sometimes referred to as “technified,” high-input coffee, tends to be robusta coffee planted in monocrop stands. Robusta originated in West Africa and performs better in hotter and wetter climates. However, few absolute statements can be made about either variety of coffee. In some climates arabica can also be planted in full sun, as it is in parts of Brazil. Shade-grown coffee, by definition, is planted among other, taller trees,...

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- C0MMODITIES

- CONCLUSION

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- INDEX

- ISLAND PRESS BOARD OF DIRECTORS