- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Robert Brown helps us see that a "thermally comfortable microclimate" is the very foundation of well-designed and well-used outdoor places. Brown argues that as we try to minimize human-induced changes to the climate and reduce our dependence on fossil fuels-as some areas become warmer, some cooler, some wetter, and some drier, and all become more expensive to regulate-good microclimate design will become increasingly important. In the future, according to Brown, all designers will need to understand climatic issues and be able to respond to their challenges.

Brown describes the effects that climate has on outdoor spaces-using vivid illustrations and examples-while providing practical tools that can be used in everyday design practice. The heart of the book is Brown's own design process, as he provides useful guidelines that lead designers clearly through the complexity of climate data, precedents, site assessment, microclimate modification, communication, design, and evaluation. Brown strikes an ideal balance of technical information, anecdotes, examples, and illustrations to keep the book engaging and accessible. His emphasis throughout is on creating microclimates that attend to the comfort, health, and well-being of people, animals, and plants.

Design with Microclimate is a vital resource for students and practitioners in landscape architecture, architecture, planning, and urban design.

Brown describes the effects that climate has on outdoor spaces-using vivid illustrations and examples-while providing practical tools that can be used in everyday design practice. The heart of the book is Brown's own design process, as he provides useful guidelines that lead designers clearly through the complexity of climate data, precedents, site assessment, microclimate modification, communication, design, and evaluation. Brown strikes an ideal balance of technical information, anecdotes, examples, and illustrations to keep the book engaging and accessible. His emphasis throughout is on creating microclimates that attend to the comfort, health, and well-being of people, animals, and plants.

Design with Microclimate is a vital resource for students and practitioners in landscape architecture, architecture, planning, and urban design.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Design With Microclimate by Robert D. Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

EXPERIENTIAL

We've gotten pretty used to being thermally comfortable. Temperatures of our indoor environments are so well regulated that we are cozy warm on the coldest winter days and pleasantly cool on the hottest summer days. In contrast, though, many of our outdoor environments are not thermally comfortable. We have to lean into bitterly cold winter winds as we slog through slush to get from our car to the store. We have to endure withering heat as we try to find a place to eat our lunch outside on beautiful, sunny summer days. But it doesn't have to be that way. Outdoor environments can be designed to be thermally comfortable in almost any weather conditions and at almost any time of the day or year. This book will help you learn how to do it.

People love to spend time outside—strolling, interacting with nature, gossiping with friends, visiting shops, lingering over a cappuccino in an outdoor café. Landscape architects and urban designers strive to design places that encourage these kinds of activities, places where people will want to spend their time. However, their designs often focus on such elements as physical attractiveness, functionality, and composition. These are all important, of course, but without one invisible, intriguing component of the landscape they are doomed to failure. Unless people are thermally comfortable in the space, they simply won't use it. Although few people are even aware of the effects that design can have on the sun, wind, humidity, and air temperature in a space, a thermally comfortable microclimate is the very foundation of well-loved and well-used outdoor places.

When we are fortunate enough to see something through new eyes, it can be a powerful learning experience. It can provide sudden insight and depth of understanding that can change our lives forever. I hope that this book will change your perspective on the value of considering microclimate in designing outdoor spaces. I have found that people have a perspective on microclimate that they have gained through many years of living with and experiencing it. Yet this experiential understanding is usually far from complete—and, often, is completely wrong.

Let's take an everyday situation of walking toward a tall building with a moderate to strong wind at your back. As you near the building, you notice that the wind seems to shift directions and is now coming out of the building toward you. Have you every wondered how that could be? Well, here is what is happening. In general, the wind increases in speed the higher you go above the ground, so the wind that encounters the front of the building near the top is traveling faster than the wind at ground level. When it reaches the building, it has to go somewhere—some of it goes up and over the building, some around the sides, and some down the face, all the while maintaining much of its speed. When the wind that flows down the front reaches the ground, it again has to go somewhere, and much of it ends up flowing away from the face of the building. It's as if it is rebounding from the building, and you experience it as if it is flowing out of the building. So the next time you see images of people struggling against the wind to get into a building, picture the mechanism that has caused that to happen. You will never think of the wind around a building in the same way again. And that's really the intent of this book: to help you see and understand microclimates, maybe not so that your eyes can see them but so that your mind can.

We are all experiencing microclimates at all times—it's almost like walking around in your own personal microclimatic bubble—but most of us are totally unaware of it and don't understand or appreciate its importance. Much of the microclimate is totally invisible to us—unless it is brought to our attention in a way that we can visualize, we don't even know that it's there—but nevertheless it can play a very important role in our lives.

When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time at my grandparents' farm in Saskatchewan, Canada. I remember the winters the most. A cold wind was always blowing from the west. When my brothers and I would be shooed outside to play, we knew that when we got cold we could go around to the south side of the house and squat down beside the lone spruce tree in the yard. There was hardly any wind there, and the sun felt like warm hands on our frozen cheeks and noses. I never questioned why it would be so much warmer there than anywhere else in the landscape. That's just the way it was.

People have been seeking warm places on cold days for a very long time. Evidence points to a time about forty thousand years ago when some people decided to wander out of Africa and start to live in less-than-warm-all-the-time climates, and ever since we've tried to figure out ways to stay warm on cool days.

Those people who stayed in Africa didn't have to spend much time trying to stay warm. The climate throughout most of Africa was, and still is, generally pretty comfortable for people. It's tropical, subtropical, desert, or savannah, and where there's more than one season it is usually a wet season and a dry season. Much of Africa hasn't seen a frost in living memory. In fact, the people who live there spend much more time trying to keep from getting too hot than they ever do trying to keep from getting cold.

A few years ago, I was working on a research project in the remote villages of Malawi, a tiny country in southern Africa. My Malawian research partners and I would converse with local communities about the way they use their land and how we might be able to help them achieve some of their goals.

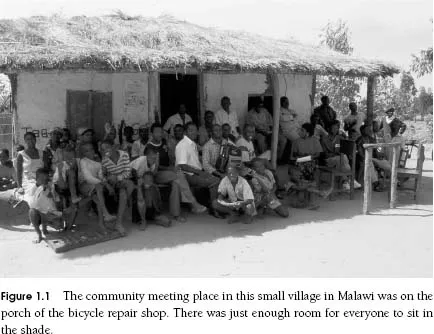

I found it interesting to see where we would hold our community meeting. It was always selected by the village headman, it was always outside, and it was always a place that was pleasantly cool. In one village, it was in the shade of the bicycle repair shop (see figure 1.1). Even on the hottest days that I experienced in Africa, these community meeting places were always comfortably cool.

The villages we visited didn't have electricity, so it goes without saying that they didn't have air-conditioning available to cool them off on hot days. They have to use whatever is at hand, and they have learned through trial and error over a very long time what works and what doesn't. Traditional methods of building homes and communities provided a lot of shade and allowed a lot of air to flow around and through buildings. One day I talked with some local fellows who were building a home in a fishing village near Lake Chilwa—dozens of kilometers from the nearest electrical outlet. This wasn't exactly your typical beach-front property. The boats that the local fishers used were dugout canoes—quite literally, big trees that had been felled and had their insides carved out.

The homes were small, round huts made from stacks of sun-dried mud bricks, topped with a thatched roof. I was curious why they left a space between the top of the wall and the roof. The builders didn't know. They said that it was just the way houses were built in that area. It was just standard practice. When I asked if maybe the space was there to allow air to move through the hut on hot nights, they perked up and agreed that yes, in fact, the huts were quite cool at night. They had never really thought about it before, they said, but now that I mentioned it, there was often a bit of a cool breeze on hot nights. It seemed that the reason for the building form had been lost in time but that the effect of building that way continued to benefit the inhabitants.

It seems that our ancestors who decided to stay in Africa have learned to live in a hot climate and stay reasonably comfortable. But what about the ones who emigrated into regions that were not warm year-round? What about our ancestors who wandered north into Asia, Europe, and the Americas? People began to live in areas that had a distinctly cold season for part of each year. How did they stay warm?

Part of the answer, of course, is that they developed warm clothing. Animal furs can be very effective at keeping the cold out, as can many other natural fibers and materials. But warm clothing wasn't enough. People had to find locations to live that would not require them to spend too much time or energy trying to stay warm. One of the most popular early homes seems to have been caves—especially those that open toward the sun.1 People would have noticed that during hot summer days it was comfortably cool in the cave, and that during cold weather they were much warmer in the cave than they were outside. Part of this was due to the thick walls of the cave, which buffered the thermal effects of changing seasons, like good insulation in the walls of a house. But part of it was also because during the winter the sun was low in the sky and could penetrate deep into the cave—warming everything that it hit—while in the summer the high sun angle meant that the interior of the cave was shady all day.

Besides cool air temperatures, our ancestors about two thousand generations ago would have also had to deal with wind on cold days.2 The cooling effect of wind on people increases as wind speed increases and also as air temperature goes down. So people had to find a way to get out of the wind during the winter. The cave helped here as well. Wind doesn't blow into a cave very well, especially if the cave is a dead end. Any air that tries to enter the cave has nowhere to go and is effectively blocked by back pressure. The advantage of south-facing caves is that winter winds seldom blow from the south—and if they do, they aren't very cold. Cold winter winds in the northern hemisphere often blow from westerly and northerly directions, so they are effectively blocked by the walls of south-facing caves.

Through trial and error over long periods of time, people learned to create thermally comfortable environments in a wide range of climatic conditions. Although this can be a very effective technique, it takes a long time and often requires many failures along the way. We are now much more strategic in our approaches, and we use the power of electronic computing and a solid understanding of energy flow to determine the effects of design ideas on the microclimate and thermal comfort of spaces before the ideas are implemented.

The foundation of design for thermal comfort is the energy budget of a person. It's not unlike the budget that a student would have when attending university. A student typically would have a certain amount of money to spend each year, and if more goes to tuition, then there is less available for other things. In the same way, a human body has inputs and outputs of energy, and there has to be a balance between the two or the body will become overheated or underheated. These models assume that a person's core temperature has to stay within a narrow range or the person will begin to feel uncomfortable. Keeping a human body thermally comfortable in changing seasons is no mean feat. Your internal body temperature can range from only about 36°C to 38°C (roughly 97°F to 100°F); if it goes lower than that, you are risking hypothermia, and going higher than that could bring on hyperthermia—and death! That's a remarkably narrow range, especially considering how much air temperature can change throughout the year. I've huddled against –50°C (–58°F) winds in northern Manitoba and perspired through +50°C (122°F) temperatures in Death Valley, California. And all that time I was maintaining an internal body temperature of 37°C (98.6°F) plus or minus one degree. Amazing!

The first study to look in detail at the internal temperatures of people was done in Germany. It reported that the average temperature of human cores is 37°C. The study was translated into English, and the temperature was converted to Fahrenheit, resulting in the well-known value of 98.6°F as the normal temperature. Lost in translation was that the original study calculated an average of all the temperatures measured and then rounded the answer off to the nearest degree Celsius. A mathematically valid conversion would round off the answer to the nearest Fahrenheit degree as well. The number after the decimal (the .6) gave the impression of a value that was known to the nearest tenth of a degree, while in fact it was recorded and reported to only the nearest degree. Now that more careful measurements have been taken with more precise and accurate instruments, it is well accepted that the average normal internal temperature of a person is 98.2°F plus or minus 0.6°F. Anything within the range of 97.6° to 98.8°F is completely normal. So the value that everyone knows—that our normal temperature is 98.6°F—is wrong. It is the remnant of a poorly translated scientific study.

This average normal internal temperature of a person is the important starting point of energy budget modeling. From this point we consider flows of energy to and from the body. The human body really has only two main sources of energy or heat available to it. The first source of heat is that generated inside the body through metabolism. The more work you do, the more heat you generate. When I do my sloth imitation in front of the television on Sunday afternoon, I'm not generating much metabolic energy—probably about 60 watts for every square meter of surface area of my body (W/m2). Even if I really speed up my arm as it moves those chips toward my mouth, or if I move my thumb super fast on the remote control, I'm not going to generate more than a few more watts. Contrast that to the rare times I get out and toss around a football for half an hour. Before I've chased down many bad throws, I'll be generating upward of 250 W/m2 and will find myself taking off layers of clothing to cool down.

The other main source of energy available to our bodies is radiation. Now, for those of us who grew up with parents warning us of the dangers of radiation—from microwave ovens to nuclear power plants—the idea of using radiation to warm ourselves can be frightening. But this is a different kind of radiation, one you experience all the time. The largest amount of radiation available to heat our bodies comes from the sun and is known as solar radiation. It's more than just sunlight, though; a good portion of it—about half—is invisible to the human eye. It's there but we can't see it. If that isn't weird enough, the other source of radiant energy is being emitted by everything around us. This book, the walls, everything surrounding us, is emitting radiation all the time, and it's also invisible to the human eye. There's invisible radiant energy all around us, Scotty. It sounds like a script for a sci-fi movie.

I'll spare you the details of radiation for now, but let me just say that after all these years of living with radiation, and studying it in almost every way possible, we still don't really know what it is or how it works. Or maybe I should say, we have lots of ways of understanding and describing it, but these ways depend on how we are looking at it. In some ways, radiation acts like a wave, much like those in the ocean. It has peaks and valleys, and the distance between peaks determines the wavelength. When we see different colors, we are seeing different wavelengths of light. Blue light has a shorter wavelength (the peaks of the waves are closer together) than red light. When the wavelengths get much shorter than blue or much longer than red, our eyes can no longer see them. But they're still there.

In other ways, radiation acts like little parcels of energy called photons. When plants photosynthesize solar radiation, it can be understood as taking little bundles of energy from the sunlight and using it to make plant material.

But for now, let's just think of radiation as an input into a person's energy budget. And it can be a very big input. If you stand outside on a sunny day, you could be getting upward of one thousand watts per square meter of solar energy striking your body—more than ten times the amount I was generating while lying on the couch.

In terms of inputs of energy to our bodies, that's about it—unless you are wearing electric socks or sitting in a sauna. If you're a bit chilly and want to add energy to your body, you can either generate more internal energy by working harder or move your body into the sun or near a warm surface, such as a fire or a radiator.

Now, if you've been paying attention, you might say, Hey, wait a minute…. I can warm up by putting on more clothes! While it's true that this would make you feel warmer, you wouldn't actually be adding any heat to your body. You would simply be slowing down the loss of heat from your body.

As you might expect, the ways that a human body can lose heat are as simple as the ways that it can gain heat. There are four main ways: through convection, evaporation, conduction, and—there it is again—radiation.

Convection is what happens when air moves past your body and carries away energy. As long as the air is cooler than your approximately 33°C (91°F) skin temperature, then as the air molecules collide with your skin they grab some energy and take it with them. This warms the air molecules ever so slightly and cools your skin a wee bit. Let a few billion air molecules strike your skin, however, and you will start to sit up and take notice.

The more air molecules that strike your skin, the more energy that will be carried away, which means that the faster the air is moving the more convection that will take place and the cooler you will feel. The amount of cooling that takes place also depends on the temperature difference between your skin and the air. If the air is the same temperature as your skin, then no exchange of energy will take place and there will be no convective cooling. However, when the air molecules are much colder than your skin, substantial cooling can occur.

The second way a body can shed energy is through evaporation. The most obvious, but by no means the only, way to understand this is to think about a hot day when you sweated so much that your underarms got wet. OK, maybe that's not an image you want to have—so let's imagine instead that you have a buff body and that you were exercising so hard that perspiration formed on your chest. In either case, the liquid water that oozes out of your pores and onto your skin might have an opportunity to evaporate by changing state into its gaseous form. If this happens, and it often does as long as the humidity in the air is not too high, then it takes a lot of energy with it. The loss of this energy from your body makes you feel cooler.

The third main way to lose energy from your body is through conduction. In this case, energy passes directly from your body to another object that is in contact with your body. The image that always comes to my mind when I think of conduction is one from my childhood. When I would stay over at my grandparents' place, I used to wear only light pajama bottoms to bed and in the morning couldn't afford the time it took to put on more clothes in my rush to get the best seat for breakfast (best meaning closer than my brothers to the pancake stack). The chairs in the kitchen were typical 1950s-style chairs made of enameled steel. There was no gentle, comfortable way to settle into one...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 - Experiential

- 2 - Vernacular

- 3 - Components

- 4 - Modification

- 5 - Principles and Guidelines

- Appendix

- Notes

- Recommended Reading

- Index

- Island Press | Board of Directors