eBook - ePub

Don't Be Such a Scientist, Second Edition

Talking Substance in an Age of Style

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Randy Olson first described his life-changing encounter with an acting teacher in Don't Be Such a Scientist, it seemed like the world of science was on the cusp of gaining new respect in the public eye. Through his writing, speaking, and films, Olson challenged scientists to toss out jargon in favor of a more human approach, bringing Hollywood lessons to the scientific community. Yet today, in everything from government funding cuts to climate change denial, science is under attack. And while communicating science is more crucial than ever, the scientific community still struggles to connect with everyday people.

The time is right for a new edition of Olson's revolutionary work. In Don't Be Such a Scientist, Second Edition, Olson renews his call for communication that stays true to the facts while tapping into something more primordial, more irrational, and ultimately more human. In more than 50 pages of new material, Olson brings his pioneering message to this new age, providing tools for speaking out in anti-science era and squaring off against members of the scientific establishment who resist needed change.

Don't Be Such a Scientist, Second Edition is a cutting and irreverent manual to making your voice heard in an age of attacks on science. Invaluable for anyone looking to break out of the boxes of academia or research, Olson's writing will inspire readers to "make science human"—and to enjoy the ride along the way.

The time is right for a new edition of Olson's revolutionary work. In Don't Be Such a Scientist, Second Edition, Olson renews his call for communication that stays true to the facts while tapping into something more primordial, more irrational, and ultimately more human. In more than 50 pages of new material, Olson brings his pioneering message to this new age, providing tools for speaking out in anti-science era and squaring off against members of the scientific establishment who resist needed change.

Don't Be Such a Scientist, Second Edition is a cutting and irreverent manual to making your voice heard in an age of attacks on science. Invaluable for anyone looking to break out of the boxes of academia or research, Olson's writing will inspire readers to "make science human"—and to enjoy the ride along the way.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Don't Be Such a Scientist, Second Edition by Randy Olson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Don’t Be So Cerebral

In 2000 Premiere magazine ran an article about the making of the movie The Perfect Storm. The actor Mark “Marky Mark” Wahlberg talked about filming scenes off the coast of Massachusetts and told of glancing over his shoulder and spotting gray whales passing nearby. Even though it had been six years since I had resigned from my professorship, the scientist’s eye never fades, and I couldn’t help but be tripped up by that detail. I wrote a letter to the editor of the magazine explaining that those whales were either something other than gray whales (long since extinct in the Atlantic Ocean) or stunt doubles flown in from the Pacific Ocean. They published it. A couple of months later I ended up at a Hollywood party, spotted the issue of Premiere with my letter, proudly said to the group, “Hey, everybody, listen to this,” and then proceeded to read my letter to the editor aloud. When I finished I looked up, beaming, but instead of applause I saw expressions of “Huh?” My best friend from film school, Jason Ensler, finally broke the tension by saying, “You know, the thing about Randy is, half the time he’s like the coolest guy any of us know in all of Hollywood. But the other half of the time … he’s a total dork.”

So we begin with the crazy acting teacher and some of the simple concepts she pounded into our heads night after night. There was one that emerged supreme seven years later, when I returned to working with academics. It is so simple and yet so powerful that I choose to start this first chapter with it. Most of what I have to say descends from this notion.

Here it is …

The Four Organs Theory of Connecting with the Mass Audience

When it comes to connecting with the entire audience, you have four bodily organs that are important: your head, your heart, your gut, and your sex organs. The object is to move the process down out of your head, into your heart with sincerity, into your gut with humor, and, ideally, if you’re sexy enough, into your lower organs with sex appeal.

That’s it. Others have heard me mention this in talks and put their own spin on it—talking about the chakras and “mind body spirit” and other sorts of New Agey gobbledygook. Also, there’s vast work in the field of psychology exploring these sorts of dynamics. Carl Jung talked about personality types, and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, developed during World War II, explores this vertical axis of powers in the body. But, for our purposes, let’s keep it simple and free of psychobabble. If you’ve had lots of classes in psychology, you may find this annoyingly simplistic. If not, I hope you’ll find it as useful as I have.

It’s about the difference between having your driving force be your head and having it be your sex organs. There is a difference.

Let’s begin by considering each of the four organs.

The head is the home for brainiacs. It is characterized (ideally) by large amounts of logic and analysis. When you’re trying to reason your way out of something, that’s all happening in your head. Things in the head tend to be more rational, more “thought out,” and thus less contradictory. Academics live their lives in their heads, even if it results in their sitting at their desks and staring at the wall all day, as I used to at times. “Think before you act” are the words they live by. When they ask, “Are you sure you’ve thought this through?,” they are reflecting a sacrosanct hallmark of their entire way of life.

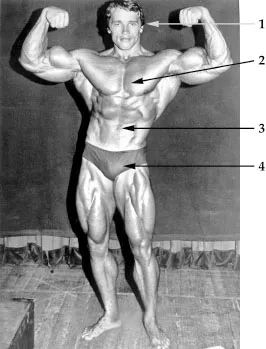

Figure 1–1. The four organs of mass communication. To reach the broadest audience, you need to move the process out of the head (1) and into the heart (2) with sincerity, into the gut (3) with humor and intuition, and, ideally, if you’re sexy enough, into the lower organs (4) with sex appeal. Photo in the public domain; accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

The heart is the home for the passionate ones. People driven by their hearts are very emotional, deeply connected with their feelings, prone to sentimentality, susceptible to melodrama, and crippled by love. Religion tends to pour out of the heart, and religious followers feel their beliefs in their hearts. Actors usually have a lot of heart. Sometimes annoyingly so. In an episode of Iconoclasts on Sundance Channel, you can see it when Renée Zellweger (heart-driven actor) and Christiane Amanpour (head-driven reporter) visit the World Trade Center memorial in New York City. Renée is overflowing with emotion, crying for the people who died, agonizing over the tortured fate of humanity, practically throwing herself to the pavement in empathetic agony, while Christiane offers up analytical, dry-eyed, rational commentary on how sad it is that humans do terrible things like this (which she’s seen firsthand all around the world in her reporting). It’s a perfect side-by-side comparison of head versus heart.

The gut is home to both humor and the deeper levels of instinct (having a gut feeling about something). We’re getting a long way away from the head now, and, as a result, things are characterized by much less logic and rationality. Humor tends to come from the gut, producing “belly laughs,” but also is extremely variable and often hard to understand. There’s nothing worse than someone trying to explain why a joke is funny.

People driven by their gut are more impulsive, spontaneous, and, most important, prone to contradiction. Where the cerebral types say, “Think before you act,” the gut-level types say, “Just do it!” When things reside in the gut, they haven’t yet been processed analytically. For that reason, when people have a first gut instinct about something, they generally can’t explain why they have the instinct, where it comes from, or how exactly it works. As a result, if you quiz them about it, you’re going to find they are full of contradictions. You’ll end up saying, “But wait, you just said X is the cause, and now you’re saying Y is the cause.” And they will respond with crossed eyes and a look that says, “I know! Can you believe I’m so confused?” And yet they are still totally certain they understand what’s going on.

We heard a lot about the gut-versus-head divide during the 2004 presidential race between George W. Bush and John F. Kerry. Bush even proudly spoke of how he based much of his decision making at the gut level. He told author Bob Woodward, “I’m a gut player. I rely on my instincts.” Not surprisingly, Bush’s presidency was characterized by a great deal of contradiction.

At the bottom of our anatomical progression we have the naughty sex organs. As soon as you finished reading that sentence, you probably smiled for reasons you don’t even begin to understand. All I have to say is “penis” and you’re either physically smiling or internally smiling. Why is this? Well, let’s ask Bill Clinton—remember him? He’s the man who obliterated his entire historical legacy thanks to this region. Let’s ask the countless men and women who, over the ages, have risked and destroyed everything in their lives out of sexual passion.

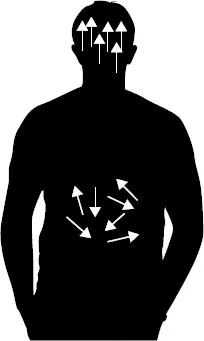

There is no logic to the sex organs. Look at those arrows in the gut in figure 1–2. Now picture them moved lower and spinning in circles. You’re a million miles away from logic in this region. And yet the power is enormous, and the dynamic is universal.

Figure 1–2. Intuition resides in the gut and tends to be full of contradiction. When the process is moved up to the head (intellectualized), the information is channelized, making it more consistent and logical.

Not universal, you think? Some people have no sex drive? That is, of course, impossible to test, but one thing worth taking a look at is the life of the novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand. She was one of the most prominent popular figures to suggest it is possible not to be driven by such irrational forces. She authored the massively best-selling Atlas Shrugged in the 1950s and founded her “objectivist” school of thought and way of life on the principle of suppressing one’s irrational side. And guess how her life turned out. She eventually got eaten alive by her sex organs.

Seriously. One of the greatest books I’ve ever read was Barbara Branden’s biography of her, The Passion of Ayn Rand. In a nutshell, Barbara and her husband, Nathaniel, became followers of Rand, went to work for her, and believed and lived every word of her teaching about living an objectivist life—not allowing oneself to be controlled by pointless, frivolous, irrational thoughts and feelings. Rand’s objectivist school of thought in the 1950s grew to enormous popularity; its followers even included former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan. And then …

Rand ended up secretly boinking Nathaniel for a couple of decades. When he dumped her, Rand turned vitriolic, and the public began to catch glimpses of the insanity she was living (proof that the story wasn’t just Branden’s fantasy). Total hypocrisy of the highest magnitude—telling the world to suppress its irrational side while viciously shoving the man who had scorned her out of her institute. According to Branden, Rand went to her grave still simmering with rage over it.

So don’t even begin to think that the lower organs are not a universal driving force, for everyone from the local FedEx delivery guy to the president of MIT. And once you’ve processed that thought, you can appreciate the ageold adage “Sex sells.” It’s the truth, mate. If you are fortunate enough to get your communication down into that region, you can connect with almost every living human—even the most anti-intellectual NASCAR fan. Who doesn’t like Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie? They’re sex-eeeee.

Too Heady: The Less Than One Campaign

Now, if we consider these organs, we start to see some fundamental differences in the members of the mass audience. The lower organs include everyone, but as we move upward, our audience narrows. There are people who pretty much respond only to sex and violence. Not much of a sense of humor, not much passion, and zero intellect. Once you move above the belt, you’ve lost them.

You still have the attention of a lot of people through humor—most folks love humor. But then you move higher and lose that element. Well, with the heart you still have actors and the religious folks. But then you move up above that, into the head, and who do you have left? Just the academics. Which is okay, but the point is that you’re communicating now with a very small audience. You’ve left most of the general public out of the story.

So this is the fundamental dynamic. And it began to resonate with me in 2001 as I drifted back from the Hollywood environment I had been immersed in since leaving academia in 1994. I started working with academics and science communicators in ocean conservation. And as I did, the words of that acting teacher began echoing back at me.

I learned of a large project called the Less Than One campaign. The idea was built around someone’s revelation that less than 1 percent of America’s coastal waters are protected by conservation laws. Someone thought, “If we can communicate this factoid to the general public, when people hear it they will think about how small 1 percent is and they’ll be outraged.”

Well. They should have called it the Less Than Outraged campaign, since that’s what happened with the general public. The Less Than One campaign opened its website in July 2003. It had a number of ill-conceived media projects (I’ll talk about one of them in chapter 4), and, to make its short story short, by July 2004 the site was gone and not a trace of the project could be found on the Internet.

Suffice it to say, the masses simply do not connect with “a piece of data” (i.e., a number). Could you imagine a presidential candidate making his campaign slogan “More than 60 percent!” with the explanation that, if you elect him, eventually more than 60 percent of the public will earn more than $30,000 a year? For some reason I just can’t see the crowd at campaign headquarters shouting, “More than 60 percent! More than 60 percent!” Sounds like something from a Kurt Vonnegut novel.

No, in fact groups connect with simple things from the heart—“A new tomorrow,” “We’ve only just begun,” “Yes we can.” You just don’t see a lot of facts and figures in mass slogans, unless they’ve been crafted by eggheads.

By now you may be thinking, “What’s this guy got against intellectuals? He’s calling them brainiacs and eggheads.” Well, I spent six wonderful years at Harvard University completing my doctorate, and I’ll take the intellectuals any day. But still, it would be nice if they could just take a little bit of the edge off their more extreme characteristics. It’s like asking football players not to wear their cleats in the house. You’re not asking them not to be football players, only to use their specific skills in the right places.

Kicking Flowers: The Value of Not Thinking Things Through

I’m criticizing overly cerebral people here, yet we obviously know there is a value to working from the head most of the time. Educated people make great inventions, create important laws, run powerful financial institutions. Clearly it pays to think things through so that everything is logical, fair, and consistent. But what’s not so obvious is the value of sometimes not thinking things through.

Spontaneity and intuition reside down in those lower organs. They are the opposite end of the spectrum from cerebral actions. And while they bring with them a high degree of risk (from not being well thought through, obviously), they also offer the potential for something else, something magical, something that is often too elusive even to capture in words. And because they are so potentially effective, they are the focus of the rest of this chapter.

I learned about the power of spontaneity the hard way—by getting yelled at in that acting class. I eventually got to see it up close and personal as I began to realize I was a lousy actor. And the reason for my being a lousy actor was that I was … too cerebral. I thought too much.

Let me tell you specifically how I would get to see it. Night after night we would do acting exercises in which one person pretends to be at home and the other person comes home. On the edge of the stage was a fake wall with a door that the person coming home would enter. So, for example, I would be the guy at home, maybe working on balancing my checkbook, and my “wife” would come in after a long day of work. We would get into an argument over something, and then, right in the middle of the scene, I would accidentally do something that wasn’t in the plan—like, let’s say, knock over the vase of flowers on the table. The contents would spill all over the floor. I would look down. And then, being the highly cerebral former academic, I would start thinking.

I would think, “Wow, I just knocked over the flowers, that wasn’t supposed to happen, we’re supposed to be arguing over the wrecked car, how would this clumsy act I just did fit into my c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction to the Second Edition

- Chapter 1 Don’t Be So Cerebral

- Chapter 2 Don’t Be So Literal-Minded

- Chapter 3 Don’t Be Such a Poor Storyteller

- Chapter 4 Don’t Be So Unlikeable

- Chapter 5 Don’t Be Such a Poor Listener

- Chapter 6 Be the Voice of Science!

- Appendix: Filmmaking for Scientists

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index