eBook - ePub

Suburban Remix

Creating the Next Generation of Urban Places

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Suburban Remix

Creating the Next Generation of Urban Places

About this book

The suburban dream of a single-family house with a white picket fence no longer describes how most North Americans want to live. The dynamics that powered sprawl have all but disappeared. Instead, new forces are transforming real estate markets, reinforced by new ideas of what constitutes healthy and environmentally responsible living. Investment has flooded back to cities because dense, walkable, mixed-use urban environments offer choices that support diverse dreams. Auto-oriented, single-use suburbs have a hard time competing.

Suburban Remix brings together experts in planning, urban design, real estate development, and urban policy to demonstrate how suburbs can use growing demand for urban living to renew their appeal as places to live, work, play, and invest. The case studies and analyses show how compact new urban places are already being created in suburbs to produce health, economic, and environmental benefits, and contribute to solving a growing equity crisis.

Above all, Suburban Remix shows that suburbs can evolve and thrive by investing in the methods and approaches used successfully in cities. Whether next-generation suburbs grow from historic village centers (Dublin, Ohio) or emerge de novo in communities with no historic center (Tysons, Virginia), the stage is set for a new chapter of development—suburbs whose proudest feature is not a new mall but a more human-scale feel and form.

Suburban Remix brings together experts in planning, urban design, real estate development, and urban policy to demonstrate how suburbs can use growing demand for urban living to renew their appeal as places to live, work, play, and invest. The case studies and analyses show how compact new urban places are already being created in suburbs to produce health, economic, and environmental benefits, and contribute to solving a growing equity crisis.

Above all, Suburban Remix shows that suburbs can evolve and thrive by investing in the methods and approaches used successfully in cities. Whether next-generation suburbs grow from historic village centers (Dublin, Ohio) or emerge de novo in communities with no historic center (Tysons, Virginia), the stage is set for a new chapter of development—suburbs whose proudest feature is not a new mall but a more human-scale feel and form.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Suburban Remix by Jason Beske, David Dixon, Jason Beske,David Dixon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I SETTING THE STAGE

Part I sets the stage with an overview on the origin and essential importance of walkable urban places followed by a rapid history of suburbia from before the Civil War to the Great Recession. It describes how the demographic, social, and economic forces collectively termed the “Great Reset” will create a far more urban future for suburbia.

1

Urbanizing the Suburbs

The Major Development Trend of the Next Generation

The Built Environment

The dawning of the twenty-first century in the United States has seen a structural shift in how the country creates its built environment (defined as infrastructure and real estate). The suburbs have played the major role for a century, but that role is fundamentally changing. Understanding the implications of this structural shift requires the introduction of a few basic concepts.

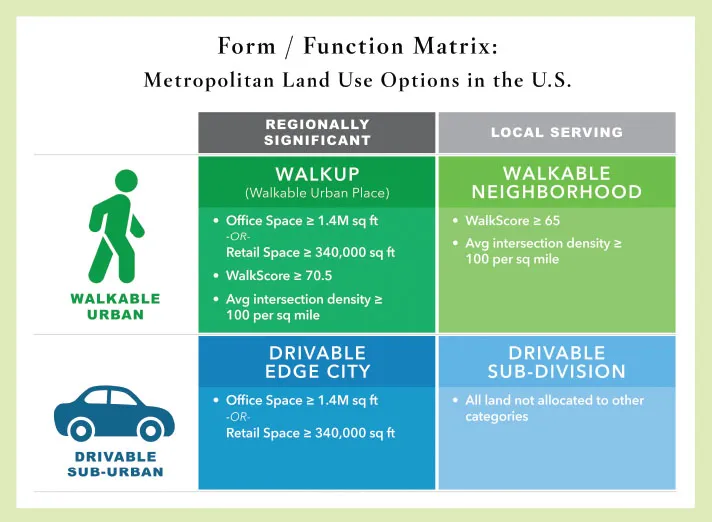

First, it is important to understand that the built environment takes two basic forms: walkable urban and drivable sub-urban. There are many variations, but broadly speaking there are just these two.

Walkable Urban Development

Walkable urban development is the oldest form employed in building cities and metropolitan areas. This type of development has been the basis for how we have built our cities since Çatalhöyük (in present-day Turkey) was built around 9,500 years ago—the oldest city known to date. Walking is the primary means of getting to and getting around a walkable urban place. The distance that most people feel comfortable walking is about 1,500 to 3,000 feet, which limits the geographic size of a walkable urban place. Research conducted at George Washington University has shown that the average walkable urban place in metropolitan Washington, DC, is 408 acres, about the size of three regional malls, including their parking lots.

Beyond that distance, most people will use another means of transport if it is available. Historically that has meant a horse, a horse-drawn wagon, a bike, public transit (rail or bus), or a car. Within that defined and confined walkable urban place, walking provides access to many if not all everyday needs—shopping, social life, education, civic life, and maybe even work. This mixed-use character means the walkable urban place has a relatively high density; measured by gross floor area ratios (FARs, measuring all land within the area being evaluated, including right of way), between 1.0 and 30. The lowest walkable urban density, such as a small town, could be 1.0, whereas high walkable urban density, like Midtown Manhattan, is about 30 FAR. However, most walkable urban places developed today, particularly those in the suburbs, range between 2.0 and 4.0 FAR, assuming they are employment, destination retail, or civic places (defined later as regionally significant places).

Drivable Sub-urban Development

The second form of built environment is drivable sub-urban development (the hyphen is used to indicate that it is a fundamentally different from and less dense than walkable urban). Drivable sub-urban development segregates the various needs of everyday life one from the other—retail is in a shopping center, work is in a business park, housing is in a subdivision—and the only way to connect these is by car. Walking is generally not a safe or viable option, nor is generally any other form of transportation, such as public transport or biking. The early twentieth-century introduction of cars as a means of transportation was the obvious prerequisite for the drivable sub-urban form of development, enabling a never-before-known alternative form of building and living.

Drivable sub-urban has extremely low-density development compared to walkable urbanism, generally less than 20% of the density as measured by FAR. FAR tends to range between 0.005 and 0.40. Its various land uses—for-sale housing, rental housing, office, industrial, retail, civic, educational, medical, hotel, and more—spread out across vast swaths of land. In other words, sprawl. Most real estate developers and investors, government regulators, and financiers have come to understand this model extremely well, turning it into a successful development formula and economic driver for the midand late twentieth century. Drivable sub-urban development provided a foundation for the economy and “fueled” the dominant industry of the industrial era—the building of automobiles and trucks, including the support industries of road building, finance, insurance, and oil. Drivable sub-urban development was essential to American economic growth in the mid- to late twentieth century.

Economic Functions of the Built Environment

Metropolitan land use supports either regionally significant or local-serving functions.

Regionally Significant Locations

Regionally significant locations, sometimes referred to as submarkets by commercial brokers, are used for the following purposes:

- Concentrations of jobs

- Civic centers

- Institutions of higher education

- Major medical centers

- Regional retail

- One-of-a-kind cultural, entertainment, and sports facilities

Regionally significant land constitutes less than 5% of all metropolitan landmass, according to George Washington University School of Business (GWSB) research, yet it is where the region’s wealth is created, where many one-of-a-kind facilities prefer to locate, and where regionally significant retail outlets locate (e.g., malls, concentrations of specialty stores, big box stores, flea markets, and major farmer’s markets). GWSB research in metropolitan Boston has shown that regionally significant walkable urban places account for 1.2% of the metro landmass and regionally significant drivable sub-urban locations represent 2.5% of the metro landmass.

Regionally significant places are generally net fiscal contributors for local jurisdictions; that is, the tax revenues they produce (income, sales, property, and other taxes) exceed the costs of the government services they receive (transportation, police, fire, regulatory, legal, etc.). This land use function is generally the reason a metropolitan economy—and therefore the metropolitan area—exists.

Local-Serving Locations

Local-serving locations are bedroom communities dominated by residential development and complemented by local-serving commercial uses (e.g., grocery stores) and civic uses (e.g., primary and secondary schools, police and fire stations, etc.). The vast majority of the local-serving land is residential, either for-sale or rental properties, whereas the minority of the land supports commercial development, generally for retail (e.g., grocery stores).

Local-serving drivable sub-urban land use accounts for the vast majority (~ 92%) of the total metropolitan landmass. Local-serving locations are generally net financial losers for local jurisdictions; that is, they produce less in tax revenues (income, sales, property, and other taxes) than they cost in terms of public services (transportation, police, fire, regulatory, and legal services, but especially education). In other words, most local-serving jurisdictions have to be subsidized by regionally significant land uses within the jurisdiction or they would have to raise their taxes substantially to pay for these services.

Generally speaking, regionally significant locations are where the metropolitan area earns its living, and local-serving places are where most residents spend their nonwork lives and the income and surplus generated by regionally significant locations.

Form Meets Function

The two forms and two functions of metropolitan land use produce a simple four-cell matrix, shown in Figure 1.1. This matrix outlines the land use options available for any metropolitan land and includes an estimate of the metropolitan land used for each form/ function combination. The upper-left cell, regionally significant walkable urban places, are called WalkUPs. They are the focus of the urbanization of the suburbs, as will be shown here.

The “Foot Traffic Ahead” research from the Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis at GWSB surveys the walkable urbanism of three real estate products (office, retail, and rental apartments) of the 30 largest metropolitan areas in the United States. It demonstrates that there are eight types of regionally significant WalkUPs12:

- Downtown—the traditional center of the metro’s central city

- Downtown adjacent—surrounding the downtown, such as Dupont Circle in Washington, DC, Capitol Hill in Seattle, and Uptown in Dallas

- Urban commercial—local-serving commercial districts that went into decline in the late twentieth century but have experienced a recent revival as regionally significant WalkUPs, such as Columbia Heights in Washington, DC, Lincoln Park in Chicago, and West Hollywood in Los Angeles

- Urban university—institutions of higher learning that have embraced their community, such as UCLA in Los Angeles, Penn and Drexel in West Philadelphia, and Columbia in New York

- Innovation district—described by the Brookings Institution as “geographic areas where leading-edge anchor institutions and companies cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators, and accelerators,” such as Kendall Square Innovation District in Cambridge, Massachusetts (sponsored by MIT and the developer Forest City), University City Science Center in West Philadelphia (sponsored by the colleges and universities in the region, led by the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel), and Cortex in St. Louis (sponsored by Washington University and various health care and civic institutions)

- Suburban town center—eighteenth- and nineteenth-century towns that the metro area grew to include and that have also enjoyed a recent revival, such as Evanston in metro Chicago, Bellevue in metro Seattle, and Pasadena in metro Los Angeles

- Redeveloped drivable sub-urban—strip and regional malls that have urbanized, such as Belmar in metro Denver, Tysons in metro Washington, DC, and Perimeter in metro Atlanta

- Greenfield/brownfield development—complete walkable urban developments built from scratch, such as Reston Town Center in metro Washington, DC, Atlantic Station in metro Atlanta, and Easton Town Center in metro Columbus

Figure 1.1. Types of WalkUPs: Central City versus Suburb. (Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis at the George Washington University School of Business)

The first five WalkUP types tend to locate in the central city. The last three types tend to be in the sub...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Setting the Stage

- Part II: Suburban Markets

- Part III: Case Studies for Walkable Urban Places

- Part IV: Bringing it All Together

- Conclusion

- About the Contributors

- Index