eBook - ePub

A New Coast

Strategies for Responding to Devastating Storms and Rising Seas

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"This is a timely book… [It] should be mandatory reading..." — Minnesota Star Tribune

More severe storms and rising seas will inexorably push the American coastline inland with profound impact on communities, infrastructure, and natural systems. In A New Coast, Jeffrey Peterson draws a comprehensive picture of how storms and rising seas will change the coast. Peterson offers a clear-eyed assessment of how governments can work with the private sector and citizens to be better prepared for the coming coastal inundation.

Drawing on four decades of experience at the Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Senate, Peterson presents the science behind predictions for coastal impacts. He explains how current policies fall short of what is needed to effectively prepare for these changes and how the Trump Administration has significantly weakened these efforts. While describing how and why the current policies exist, he builds a strong case for a bold, new approach, tackling difficult topics including: how to revise flood insurance and disaster assistance programs; when to step back from the coast rather than build protection structures; how to steer new development away from at-risk areas; and how to finance the transition to a new coast. Key challenges, including how to protect critical infrastructure, ecosystems, and disadvantaged populations, are examined. Ultimately, Peterson offers hope in the form of a framework of new national policies and programs to support local and state governments. He calls for engagement from the private sector and local and national leaders in a "campaign for a new coast."

A New Coast is a compelling assessment of the dramatic changes that are coming to America's coast. Peterson offers insights and strategies for policymakers, planners, and business leaders preparing for the intensifying impacts of climate change along the coast.

More severe storms and rising seas will inexorably push the American coastline inland with profound impact on communities, infrastructure, and natural systems. In A New Coast, Jeffrey Peterson draws a comprehensive picture of how storms and rising seas will change the coast. Peterson offers a clear-eyed assessment of how governments can work with the private sector and citizens to be better prepared for the coming coastal inundation.

Drawing on four decades of experience at the Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Senate, Peterson presents the science behind predictions for coastal impacts. He explains how current policies fall short of what is needed to effectively prepare for these changes and how the Trump Administration has significantly weakened these efforts. While describing how and why the current policies exist, he builds a strong case for a bold, new approach, tackling difficult topics including: how to revise flood insurance and disaster assistance programs; when to step back from the coast rather than build protection structures; how to steer new development away from at-risk areas; and how to finance the transition to a new coast. Key challenges, including how to protect critical infrastructure, ecosystems, and disadvantaged populations, are examined. Ultimately, Peterson offers hope in the form of a framework of new national policies and programs to support local and state governments. He calls for engagement from the private sector and local and national leaders in a "campaign for a new coast."

A New Coast is a compelling assessment of the dramatic changes that are coming to America's coast. Peterson offers insights and strategies for policymakers, planners, and business leaders preparing for the intensifying impacts of climate change along the coast.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A New Coast by Jeffrey Peterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

A Warming Climate Drives Coastal Storms and Rising Seas

Reason and free inquiry are the only effectual agents against error.

1

Coastal Storms, Coastal Nightmare

Major coastal storms are killers. Looking back on the human costs of Hurricane Harvey, which hit the coast of Texas in late August 2017, the Houston Chronicle memorialized the seventy-five people killed in the resulting flooding: “A beloved pastor and his wife swept away by a raging creek in Fort Bend County. An elderly man who died alone, trapped by rising waters in his west Houston home. Six members of the Saldivar family trying to escape the torrential rains. A dedicated police officer who could not ignore his duty. Those are among the many whom this storm took from us, and many others whose names we don’t yet know.”1

Just a week later, Hurricane Irma, the strongest Atlantic basin hurricane ever recorded, devastated the Caribbean, the Florida Keys, and the western coast of Florida, resulting in the death of ninety-two people in the United States, including seventy-seven in Florida.2 The Florida Sun Sentinel interviewed a resident of Cudjoe Key: “It’s been a nightmare…. You live here in a resort, everything’s nice and pretty, and the next day it’s all gone…. Death. That’s what it sounded like to me.”3 Winds exceeded 130 miles per hour4 and sea water surged five to eight feet above ground level in the Keys.5

Then, less than a month later, on September 20, Hurricane Maria struck the island of Puerto Rico with winds of 155 miles per hour6 driving a surge of water six to nine feet high.7 The initial official death toll was sixty-four, but several organizations argued it was much higher. The New York Times reviewed differing estimates and found that 1,052 more people than usual died across the island in the forty-two days after the storm.8 A May 2018 report by researchers at Harvard University came to a much higher estimate, finding that 4,645 people died as a result of the hurricane.9 Many of these deaths are associated with lack of access to medical services or facilities or electric power. In August of 2018, the government of Puerto Rico settled on an estimate of 1,427 deaths directly due to storm damage while noting that estimates from other studies range between 800 and 8,000 deaths due to delayed health care.10

Figure 1–1. Port Arthur, Texas, was among many Texas coastal communities that suffered extensive flooding of homes, businesses, and transportation systems as a result of Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. Photo by Staff Sgt. Daniel Martinez, South Carolina National Guard.

The loss of life in these storms was tragic, but not record setting by American standards. The Galveston Hurricane in 1900 is thought to have killed between 6,000 and 12,000, with winds of over 140 miles per hour and a storm surge of fifteen feet.11 Hurricane Katrina killed at least 1,833 people in late August 2005, with wind speeds over 175 miles per hour and a storm surge of twenty-four to twenty-eight feet along the northern Gulf of Mexico.12 Hurricane Sandy brought high winds and a storm surge over nine feet at the lower end of Manhattan Island and along the New Jersey shore, claiming 106 lives, mostly from drowning,13 in October 2012. Roughly a dozen hurricanes have each resulted in over 100 deaths in the United States in the past century.14

Figure 1–2. The US Coast Guard conducts a water rescue in Jacksonville, Florida, during Hurricane Irma, September 2017. Photo by US Coast Guard.

Figure 1–3. Coast Guard Lt. Lucas Taylor provides food and water to a girl in Moca, Puerto Rico, October 2017, following Hurricane Maria. Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class David Micallef, US Coast Guard.

One factor behind the significant loss of life and damage costs of the 2017 storms is the growth of population and the value of assets along the coast. Another consideration is that the long-standing phenomena of major coastal storms is playing out against a backdrop of a warming planet. Climate models suggest that a warmer climate will result in more intense, and perhaps more frequent, coastal storms. In addition, warming temperatures are driving a gradual rise in sea levels globally and along the American coast. Rising seas will not make coastal storms more frequent or more severe but will push storm surges farther inland.

With these concerns in mind, it is worth looking more closely at the problem that connects coastal storms and rising seas: storm surge. It is also important to understand past trends in costs of major storms and how storms may change as the planet warms.

The Role of Storm Surge in Coastal Storm Deaths and Damage

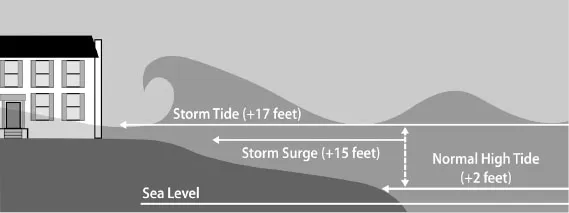

A storm surge is a wave of ocean water, over and above the predicted astronomical tide, generated by high winds and low barometric pressure associated with a coastal storm. Smaller storms combine with high tides to generate nuisance flooding or, occasionally, flooding on the “coastal flood warning” scale of several feet.

A key thing about storm surges is that the bigger the storm—the greater the winds and lower the barometric pressure—the bigger the storm surge (see fig. 1–4). Exceptionally high storm surges, such as the twenty-four to twenty-eight feet delivered by Hurricane Katrina, have occurred, but surges of five to ten feet are more common, and damages can vary widely based on the elevation of the coast. Hurricane Michael, with the third lowest barometric pressure recorded at landfall, came ashore on the Florida Panhandle with storm surges in excess of ten feet east of Panama City and fourteen feet in Mexico Beach.15

The other key thing to know about storm surges is that they are by far the deadliest element of a coastal storm. In 2014, Edward Rappaport of the National Hurricane Center published a paper looking at deaths from major storms over the past fifty years finding that, “roughly 90% of the deaths occurred in water-related incidents, most by drowning …”16 and “storm surge was responsible for about half of the fatalities (49%).”17 In contrast, high winds were estimated to have caused less than 10 percent of deaths.

Given the deadly effect of storm surges, it is very useful to know what land areas are at risk of flooding by a surge in the event of a storm. Fortunately, understanding of coastal areas at risk of storm surges has improved significantly in recent years. The National Hurricane Center within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) uses a model to “estimate storm surge heights resulting from historical, hypothetical, or predicted hurricanes.”18 The “Sea, Lake and Overland Surges from Hurricanes” model, or SLOSH for short, predicts for each basin along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts the geographic extent and depth of storm surge in the event of a given storm size (e.g., hurricane Categories 1–5).

Figure 1–4. Storm surge and tide impacts. Illustration of water level differences for storm surge, storm tide, and a normal high tide, as compared to sea level. Storm surge is the rise in sea level caused solely by a storm. Storm tide is the total observed sea level during a storm, which is the combination of storm surge and normal high tide. National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Figure 1–5. Hurricane Michael caused widespread destruction along the Florida Panhandle, including in Mexico Beach, Florida, October 2018. Photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Colin Hunt, US Coast Guard.

Drawing on the SLOSH model and other data, NOAA estimates that, “in a worst-case scenario, approximately 24 million people along the East and Gulf coasts are at risk from storm surge flooding.”19 The risk consulting company CoreLogic came to a roughly comparable conclusion in a 2018 report finding 6.9 million homes at risk of storm surge.20 NOAA found that by far the greatest number of people at risk of storm surge are in Florida, with significant populations at risk in Louisiana, New York, and New Jersey. These estimates of populations at risk of storm surge, however, are based on the land areas at risk with current sea level and do not reflect additional land area or population at risk based on future sea level, or more severe coastal storms, or growing coastal populations.

Knowing the coastal land areas most at risk of storm surge flooding in the event of a storm is a big step forward, but it would be even better to also have a sense of the risk of a major storm occurring at a specific place along the coast. The National Hurricane Center has data on that as well. This data is framed to provide a return period for major storms (i.e., hurricanes on the scale of Category 1–5) in a given coastal county, based on past experience, for the Atlantic Coast and the Gulf of Mexico.

For example, looking at NOAA’s Hurricane Strike Frequency Map, it is possible to find that Miami–Dade County, Florida, has experienced six Category 1 hurricanes, and that a storm of that scale can be expected about eighteen times over an extended period (e.g., 1900–2009) (see table 1–1).21 Because these data are drawn from past experience, it does not reflect projected increases in storm intensity due to a warming planet.

Even with these impressive statistics, however, it is impossible to know from year to year when or where a major coastal storm will form or strike. Predictions of the path and intensity of hurricanes already formed, however, are getting better, thanks to NOAA’s Hurricane Forecast Improvement Project. Started in 2009, the ten-year effort is intended to reduce errors in storm track and intensity estimates by 50 percent and extend forecasts from five to seven days.22

Past Trends in Coastal Storms

Every four years, the United States Global Change Research Program, made up of scientists from federal agencies and other organizations, publishes a national assessment of changes in the climate. The 2014 National Climate Assessment, speaks to the subject of past coastal storms: “The intensity, frequency, and duration of North Atlantic hurricanes, as well as the frequency of the strongest (Category 4 and 5) hurricanes, have all increased since the early 1980s.”23 The 2017 Climate Science Special Report, which is part 1 of the 2018 National Climate Assessment, linked these storm changes to human activity: “Human activities have contributed substantially to observed ocean—atmosphere variability in the Atlantic Ocean (medium confidence), and these changes have contributed to the observed upward trend in North Atlantic hurricane activity since the 1970s (medium confidence).”24

Table 1–1. Hurricane strike frequency data for Miami–Dade County, Florida

| Storm category | # of strikes | Return period, years |

| 1 | 6 | 18 |

| 2 | 5 | 22 |

| 3 | 8 | 14 |

| 4 | 4 | 28 |

| 5 | 2 | 55 |

Note: Return period is defined as the average recurrence interval of a hurricane of similar in magnitude over an extended period of time (e.g., 1900–2009).

Source: Data from “Hurricane Frequency,” Storm Surge Inundation Map; Miami–Dade County (click on Miami–Dade County) Environmental Protection Agency website.

Exploring the question of trends in the costs of past major coastal storms, NOAA looked at a subset of all disasters costing over a billion dollars and found steady cost increases. In 2019, NOAA concluded that, since 1980, the United States has sustained 241 weather and climate disasters where overall damages and costs reached or exceeded $1 billion (including Consumer Price Index adjustment to 2018). The total cost of these 241 events exceeds $1.6 trillion.25 The trend, however, is upward. From 1980 to 2013, a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I. A Warming Climate Drives Coastal Storms and Rising Seas

- Part II. Storms and Rising Seas Disrupt the American Coast

- Part III. A Nation Unprepared for Coastal Storms and Rising Seas

- Part IV. States, Communities, and Businesses Cope with Coastal Storms and Rising Seas

- Part V. Campaign for a New Coast

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Appendices

- Notes

- Index