eBook - ePub

Water War in the Klamath Basin

Macho Law, Combat Biology, and Dirty Politics

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Water War in the Klamath Basin

Macho Law, Combat Biology, and Dirty Politics

About this book

In the drought summer of 2001, a simmering conflict between agricultural and environmental interests in southern Oregon's Upper Klamath Basin turned into a guerrilla war of protests, vandalism, and apocalyptic rhetoric when the federal Bureau of Reclamation shut down the headgates of the Klamath Project to conserve water needed by endangered species. This was the first time in U.S. history that the headgates of a federal irrigation project were closed—and irrigators denied the use of their state water rights—in favor of conservation. Farmers mounted a brief rebellion to keep the water flowing, but ultimately conceded defeat.

In Water War in the Klamath Basin, legal scholars Holly Doremus and A. Dan Tarlock examine the genesis of the crisis and its fallout, offering a comprehensive review of the event, the history leading up to it, and the lessons it holds for anyone seeking to understand conflicts over water use in the arid West. The authors focus primarily on the legal institutions that contributed to the conflict—what they call "the accretion of unintegrated resource management and environmental laws" that make environmental protection so challenging, especially in politically divided regions with a long-standing history of entitlement-based resource allocation.

Water War in the Klamath Basin explores common elements fundamental to natural resource conflicts that must be overcome if conflicts are to be resolved. It is a fascinating look at a topic of importance for anyone concerned with the management, use, and conservation of increasingly limited natural resources.

In Water War in the Klamath Basin, legal scholars Holly Doremus and A. Dan Tarlock examine the genesis of the crisis and its fallout, offering a comprehensive review of the event, the history leading up to it, and the lessons it holds for anyone seeking to understand conflicts over water use in the arid West. The authors focus primarily on the legal institutions that contributed to the conflict—what they call "the accretion of unintegrated resource management and environmental laws" that make environmental protection so challenging, especially in politically divided regions with a long-standing history of entitlement-based resource allocation.

Water War in the Klamath Basin explores common elements fundamental to natural resource conflicts that must be overcome if conflicts are to be resolved. It is a fascinating look at a topic of importance for anyone concerned with the management, use, and conservation of increasingly limited natural resources.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Water War in the Klamath Basin by Holly D. Doremus,A. Dan Tarlock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Environmental Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A Water Crisis Exposes Political Fault Lines

The old West rubs elbows with the new in Klamath Falls.

Works Progress Administration, Oregon: End of the Trail

In 2005, the Klamath irrigation project observed its hundredth birthday, but the celebration was muted by persistent fears about the project’s future. Since the early 1990s, Klamath irrigators have struggled to maintain an irrigation economy in the face of demands that more water be dedicated to the preservation of endangered species and downstream fisheries, as well as the stresses of the national and global agricultural economy. After simmering for a decade, the tension between irrigation and species conservation came to a head during the exceptionally severe drought summer of 2001.1 For the first time in its history, the United States Bureau of Reclamation was forced to make an absolute choice between irrigation deliveries and species conservation. Believing that the law left it no choice, the bureau closed the headgates of the Klamath Project to comply with its conservation duties under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) (see fig. 1).2 This drastic action was taken after the two federal agencies responsible for the administration of the ESA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), issued biological opinions (BiOps) concluding that summer irrigation releases from the project’s main storage source, Upper Klamath Lake, would threaten the survival of protected Lost River and shortnose suckers and coho salmon.3 On April 6, 2001, the Department of the Interior announced that it would deliver no water from Upper Klamath Lake that summer.

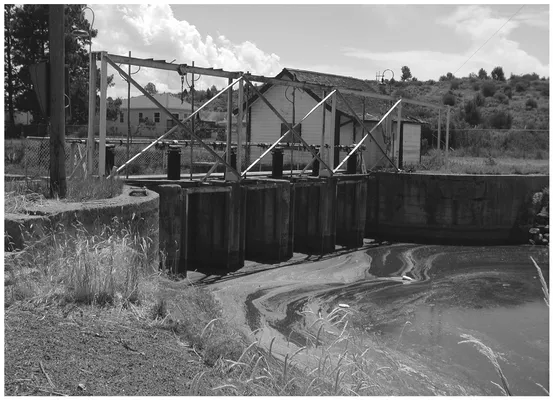

FIGURE 1

The headgates of the Klamath irrigation project stand closed in 2001. For the first time, irrigation deliveries from a federal water project were halted to protect endangered and threatened fish. (Photo by Seth Zuckerman.)

That decision would have shocked the utopian reformers and engineers who together created an irrigation-based society in the arid West in the early twentieth century. It startled and enraged the irrigators presently enjoying the benefits of a century of federal largesse. To comply with the ESA, the Bureau of Reclamation had begun to cut back water deliveries as early as 1988, but those cuts had been mild. In 2001, irrigation deliveries were reduced by 90 percent in order to protect fish. The approximately fourteen hundred farmers who rely on the Klamath Project were either unable to plant or faced severe losses on the roughly 210,000 acres they farm.4 The cutbacks triggered violence, street protests, some comic political drama, and a wide variety of other responses that continue to reverberate throughout the West.

The decision to close the headgates was made in April of 2001, before the start of the irrigation season. On May 7, thousands of area residents formed a bucket brigade to bring water from Lake Ewauna, where the Upper Klamath Lake reservoir spills into the Klamath River, to an irrigation canal near the local high school. This initial protest was peaceful and symbolic, modeled on the civil rights protests of the 1960s. But the situation soon became increasingly volatile as local frustration mounted and anti–federal government activists from across the West poured into Klamath Falls. Some protestors saw the conflict in biblical terms and called on a just God to consecrate the area as a place of liberty.5 However, impatient farmers quickly turned to an old remedy: self help. The headgates were illegally forced open several times in early July, and later a pipe was run from Upper Klamath Lake around the headgates to an irrigation canal. The local sheriff observed the trespasses and other illegal acts but refused to intervene. As a result, federal marshals and FBI agents were brought in to defend the headgates, recalling images of the forced integration of southern schools and universities after the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregation unconstitutional.

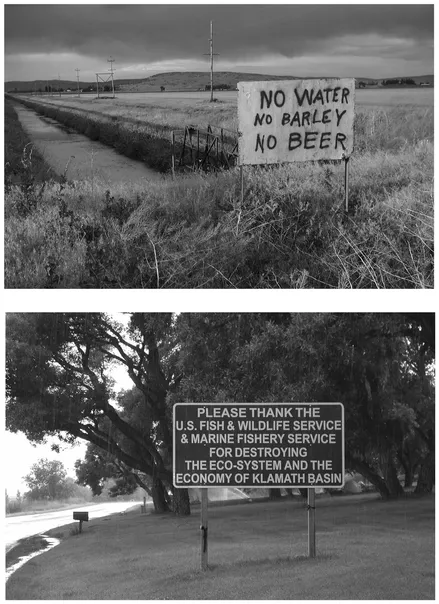

FIGURE 2

Protest signs in the Upper Klamath Basin. When the water was shut off in 2001, protest signs sprouted throughout the Upper basin. These were two of the mildest. (Photo by Seth Zuckerman.)

Tensions briefly eased that summer when Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton “found” an accounting error in the estimates of the amount of water stored in Upper Klamath Lake, allowing the Bureau of Reclamation to release about 70,000 acre-feet of water for irrigation without defying the FWS and NMFS BiOps. When those small deliveries ended, however, the protests resumed. They culminated in late August with a “Convoy of Tears” bringing sympathizers from around the West to a rally in downtown Klamath Falls that was characterized by some as “the vanguard of a citizen revolt against federal water and land management policy.”6 In an extreme example of hyperbole, former Idaho congresswoman Helen Chenoweth-Hage compared the struggle to the American Revolution. A variety of signs deploring the shutoff and attacking federal control sprouted throughout the basin that summer, as shown in figure 2.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, indirectly ended the Klamath Falls protests. The protesters withdrew to allow redeployment of federal law enforcement officers to more important national security assignments.7 A year later the headgates were demolished, replaced by multimillion-dollar new works. The events of the summer of 2001 are now officially history, as a three-hundred-pound chunk of the old headgates, like a remnant of the Berlin wall, has been put on display at the Klamath County Museum. The broader story, though, remains unfinished.

Understanding the Klamath Conflict

Since the summer of 2001, the Klamath Basin water conflict has been a symbolic rallying cry for people on both extremes of a fierce national debate about environmental protection in general and the Endangered Species Act in particular. On the one hand, this conflict is used as an illustration of the ways that property rights are “disrespected” and farmers callously pushed off lands they have sacrificed for generations to improve. One farmer characterized the headgate closure as a “land grab,”8 and the Internet is filled with sites inveighing hysterically against the ESA as a totalitarian weapon used by urban environmentalists to cleanse the rural landscape of all human imprint. Behind the invective lie powerful images with a deep grip on our national psyche, images of the Jeffersonian yeoman farmer and the romantic western cowboy. Appeals to those images allow irrigators to present themselves as victims of modern environmentalism and their battle to restore the status quo as a selfless defense of true constitutional and moral government.9

Environmentalists, too, have used the Klamath water conflict as a symbol, albeit in somewhat more measured terms. For them, it illustrates the extent to which the current federal government is willing to ignore both law and science to protect the historic resource extraction economy, supported by legal regimes put in place during the heyday of the disposition of the public domain that have brought the West’s environments to the brink of ruin. Defenders of Wildlife, for example, emphasizes the role played by White House political advisor Karl Rove in making sure that Department of the Interior officials understood that the White House favored the farmers over the fish in water allocation decisions following the 2001 crisis. The organization describes the Klamath conflict as one of several in which the George W. Bush administration “ignored science altogether in order to promote the interests of its corporate supporters—to the immediate and direct detriment of endangered species.”10

In this book, we dig below these superficial views for lessons from the Klamath experience. Those lessons are larger than the basin itself. They extend at least to the many other water conflicts throughout the irrigated West, from California to the Missouri River. Because a variety of environmental conflicts feature many of the same key elements, we believe the lessons extend well beyond the water resources of the West. They apply, in some measure, not only to all river basins but to all conflicts over limited natural resources.

In some respects, of course, the Klamath conflict is unique, shaped by the particular characteristics of this basin and its people. The basin’s geography both exacerbates and relieves water stresses. Topographically, the basin reverses the usual pattern; it is dry and flat near the headwaters and steep and wet near the mouth. That makes water conflicts tougher because it means there is no way to store water to carry the project through a dry year. By the same token, the Klamath Basin’s isolation has long helped to shield it from conflicts that have engaged the region and the nation. It remains far removed from the major urban and agricultural centers in California and Oregon. Its remote location made it one of the last areas of the Pacific Northwest investigated by trappers and one of the last opened to white settlement.11 Klamath Falls, the major community in the Upper Klamath Basin, was not served by railroad until 1909, and the railroad did not effectively tie the region to the urban centers of the West until 1926, when Klamath Falls became a stop on the main Southern Pacific Line from the Bay Area to Portland. 12 Today, Klamath Falls remains the largest community in the basin, with a population just less than twenty thousand. Unlike many areas in the West, the Klamath Basin has no growing cities to compete for its scarce water. That is both a blessing and a curse with respect to water conflicts: Although it means one less source of pressure on the resource, it also means an important source of political leverage, one that has been used in other basins to pry water away from agricultural use, is missing.

The human communities of the Klamath Basin are unique in their particulars, but they are also, in general, representative of others across the West. The waters of the West are stretched nearly to the breaking point throughout the region. 13 The Klamath Basin was simply the first place the breaking point was actually reached. The Klamath conflict brings into sharp focus the elements that make water conflicts so difficult to resolve. Upstream there are farmers and the communities that have grown up around them. Some farmers rely on federal irrigation water, while others use private irrigation works. Some grow high-value crops, while others produce only forage or pasture. Downstream there are some agricultural communities, as well as communities that are heavily dependent, economically and socially, on commercial and recreational fishing. Both upstream and downstream there are Indian tribes, struggling to maintain cultural traditions and join the economic mainstream. There are also important transient communities, visitors drawn to various parts of the basin to experience the environment.

Recurring Themes in Environmental Conflict

Looking at this conflict through the eyes of outsiders to the basin but longtime observers of environmental conflicts, we find the similarities to other contested landscapes striking. Throughout the arid West, disparate human and nonhuman communities share landscapes with limited, and highly variable, water supplies. Everyone seems to agree, on the most general level, that all the various human communities, as well as the natural community, should be respected, and that ideally all would thrive. But priorities differ radically. To us, the fundamental questions are the same across the West, across the country, and indeed around the world: Can sustainable human communities coexist with a functioning natural environment? How should conflicting demands upon limited natural resources be balanced? How can current unsustainable patterns of resource use transition into something more closely approaching harmony with the natural world?

The Klamath conflict illustrates four general themes fundamental to understanding conflicts over natural resources anywhere: the historic entrenchment of resource entitlements granted without recognition of competing interests; the clash of fundamental values closely intertwined with natural resource use; pervasive uncertainty, not just over the environmental impacts of activities but also over the priority to be assigned to competing entitlements; and a “problem-shed” extending across political and other boundaries. Each of these features helps to explain how these conflicts develop and why they are so difficult to resolve. We explore each in detail.

The Past Is Prelude

The first theme is the power of the historical context to create strong expectations that the status quo should be maintained. Environmental crises do not develop overnight. They are typically created by patterns of behavior with firm historical roots. People are often slow to realize the effect they are having on the world around them, and even on their ability to achieve their own goals. It can take a long time for the harmful effects of decisions made in good faith to become apparent. At the same time, societal goals evolve. Past decisions aimed at achieving one goal can produce consequences out of step with modern sensibilities. Yet patterns, both of private behavior and of governance, once set in place are highly resistant to change. They may become so ingrained that the idea of change is simply inconceivable to some people. Changing the law is often a necessary aspect of correcting anachronistic behavior patterns, but it is rarely sufficient for that purpose. Implementing the law in new ways is often a struggle, one that requires committed leadership to achieve success.

The fallibility of human decision making and the continuing power of past decisions are on full display in the Klamath Basin. Irrigated agriculture is the root of an environmental and social crisis that was long in the making. One of the first people to notice that crisis was Rachel Carson. In her landmark 1962 book, Silent Spring, she linked a large bird kill in the Tule Lake and Lower Klamath Lake National Wildlife Refuges to the presence of agricultural chemical residues. She prophetically observed, “All of the waters of the wildlife refuges established on . . . [Upper Klamath and Tule lakes] represent the drainage of agricultural lands. It is important to remember this in connection with recent happenings.”14 Forty years later, the crisis was apparent to any informed observer. The Upper Klamath Basin included sites with “some of the worst water quality in the state.”15 Naturally nutrient rich, Upper Klamath Lake had become hyper-eutrophic, leading to constant massive algal blooms, largely as a result of agricultural runoff. 16 Oxygen levels in the upper Klamath River fell low enough to kill thousands of fish in 1986,17 prompting the Klamath Tribe to close its c’waam fishery.18 The first-order consequences of a severe drought in an already stressed basin, like those of hurricanes and other foreseeable natural disasters, were widely understood long before the crisis came to a head. In 1999, the Oregon Water Resources Department issued a report, Resolving the Klamath, which warned the farmers that relying on the luck of rainfall that happened to be above average for a few years “will not solve the underlying problem.”19 Even the project irrigators now recognize the foreseeability of the crisis, although they accept none of the responsibility for it. In litigation seeking damages from the United States for failing to deliver their contracted water in 2001, they claimed that if the United States had taken conservation steps well before 2001, cutting off irrigation that dry summer would not have been necessary.20 Not surprisingly, though, reducing irrigation deliveries is still not on their list of acceptable conservation steps.

Even in light of societal goals at the time they were made, the water allocation decisions in the Klamath Basin were questionable. Conversion of native wetlands to farming, expansion of irrigation, and even homesteading continued until after World War II, publicly justified largely by the founding vision of the Bureau of Reclamation. That vision, in which communities of small farms provided an ideal social, political, and economic organization, was never well suited to the high desert environment. The harsh climate and remoteness from markets have always made the Upper Klamath Basin a challenge for profitable agriculture. Furthermore, the vision of rural society as the ideal was an anachronism in the United States long before the end of settlement in the Upper Klamath Basin. For better or worse, the United States was urbanizing throughout the twentieth century. By the time of the final homestead allocations in the basin, it was apparent that cities were, and would remain, the nation’s social, political, and economic centers of gravity.

The water allocation decisions made in the first half of the twentieth century in the Klamath Basin, like those in other parts of the West, have proven highly resistant to change. Only recently has growing recognition of the environmental crisis, coupled with rising political fortunes for environmental and tribal interests and the waning economic and political importance of agriculture, finally forced a confrontation. The environmental movement set the stage for change in the 1970s by winning new federal laws that, taken together, made the newly minted concept of environmental protection a legal responsibility of the federal agencies in charge of managing natural resources. The new laws endorsed what then seemed to many a heretical idea: that human beings might have to limit their demands on natural resources in order to ensure the continued functioning of the environment. The Endangered Species Act of 1973, in particular, imposed conservation duties on all federal agencies, including those, like the Bureau of Reclamation, that had previously had single-minded development missions.

Passing environmental laws did not immediately change water use in the basin. For one thing, the new conservation mandates were simply overlain on the existing missions of resource agencies. The task of reconc...

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1 - A Water Crisis Exposes Political Fault Lines

- CHAPTER 2 - A Remote, Upside-Down Watershed

- CHAPTER 3 - Reclamation Comes to the Klamath

- CHAPTER 4 - Those at the Margins: Indians and Wildlife

- CHAPTER 5 - Bringing Marginal Interests toward the Center

- CHAPTER 6 - Water Wars Become Science Wars

- CHAPTER 7 - Searching for Solutions

- CHAPTER 8 - When Is a Train Wreck a Good Thing?

- Afterword

- Notes

- Index

- Island Press Board of Directors