eBook - ePub

Design as Democracy

Techniques for Collective Creativity

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design as Democracy

Techniques for Collective Creativity

About this book

Winner of the Environmental Design Research Association's 2018 Book Award

How can we design places that fulfill urgent needs of the community, achieve environmental justice, and inspire long-term stewardship? By bringing community members to the table, we open up the possibility of exchanging ideas meaningfully and transforming places powerfully. Collaboration like this is hands-on democracy in action. It's up close. It's personal. For decades, participatory design practices have helped enliven neighborhoods and promote cultural understanding. Yet, many designers still rely on the same techniques that were developed in the 1950s and 60s. These approaches offer predictability, but hold waning promise for addressing current and future design challenges. Design as Democracy: Techniques for Collective Creativity is written to reinvigorate democratic design, providing inspiration, techniques, and case stories for a wide range of contexts.

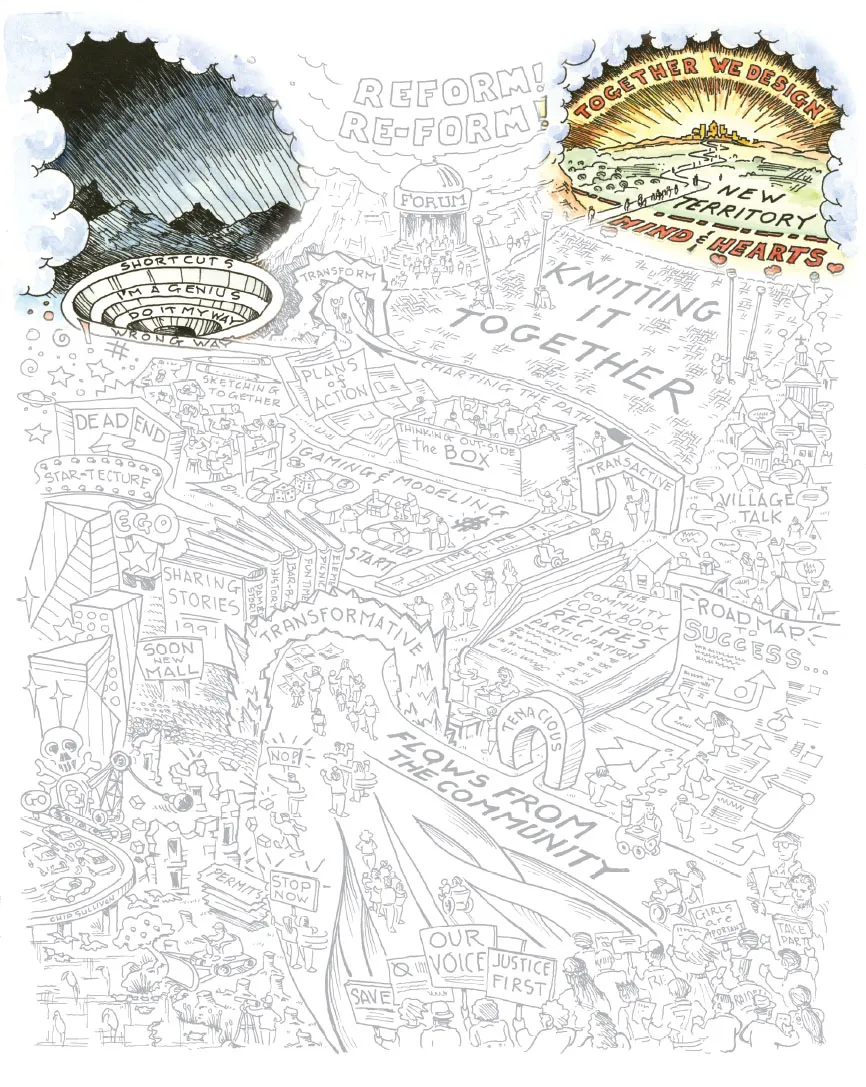

Edited by six leading practitioners and academics in the field of participatory design, with nearly 50 contributors from around the world, Design as Democracy shows how to design with communities in empowering and effective ways. The flow of the book's nine chapters reflects the general progression of community design process, while also encouraging readers to search for ways that best serve their distinct needs and the culture and geography of diverse places. Each chapter presents a series of techniques around a theme, from approaching the initial stages of a project, to getting to know a community, to provoking political change through strategic thinking. Readers may approach the book as they would a cookbook, with recipes open to improvisation, adaptation, and being created anew.

Design as Democracy offers fresh insights for creating meaningful dialogue between designers and communities and for transforming places with justice and democracy in mind.

How can we design places that fulfill urgent needs of the community, achieve environmental justice, and inspire long-term stewardship? By bringing community members to the table, we open up the possibility of exchanging ideas meaningfully and transforming places powerfully. Collaboration like this is hands-on democracy in action. It's up close. It's personal. For decades, participatory design practices have helped enliven neighborhoods and promote cultural understanding. Yet, many designers still rely on the same techniques that were developed in the 1950s and 60s. These approaches offer predictability, but hold waning promise for addressing current and future design challenges. Design as Democracy: Techniques for Collective Creativity is written to reinvigorate democratic design, providing inspiration, techniques, and case stories for a wide range of contexts.

Edited by six leading practitioners and academics in the field of participatory design, with nearly 50 contributors from around the world, Design as Democracy shows how to design with communities in empowering and effective ways. The flow of the book's nine chapters reflects the general progression of community design process, while also encouraging readers to search for ways that best serve their distinct needs and the culture and geography of diverse places. Each chapter presents a series of techniques around a theme, from approaching the initial stages of a project, to getting to know a community, to provoking political change through strategic thinking. Readers may approach the book as they would a cookbook, with recipes open to improvisation, adaptation, and being created anew.

Design as Democracy offers fresh insights for creating meaningful dialogue between designers and communities and for transforming places with justice and democracy in mind.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Design as Democracy by David de la Pena, Diane Jones Allen, Randolph T. Hester, Jeffrey Hou, Laura J. Lawson, Marcia J. McNally, David de la Pena,Diane Jones Allen,Randolph T. Hester,Jeffrey Hou,Laura J. Lawson,Marcia J. McNally,Randolph T. Hester, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Théorie et pratique de l'éducation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Suiting Up to Shed

Participatory designers provide a personal perspective that has the potential to greatly influence design outcomes. Upon hearing about a project designers begin generating ideas, and these initial ideas often help us determine what needs to be investigated, how to approach the work, and which questions to ask. Suiting up to shed focuses on techniques that prepare the design team for self-conscious, aware engagement.

A commitment to engage with community means that the team, collectively and individually, is a participant with formative experiences, values, and ideas. To suit up is to ready yourself and your team for the role you will play given the project at hand, but also to shed the pretense that participatory design is a neutral process and the designer is a neutral facilitator. As such it is important to figure out who you are, whom you are working with, and what you expect to be the underlying site and community issues. But how to do this? What will help you check your expectations and open yourself to seeing the community’s values and uniqueness?

GETTING OURSELVES READY

Slowing down at the very beginning offers opportunities to test assumptions, ground information, and build a stronger network of participants and collaborators. Many community-based projects are complex in nature and require multiple perspectives and skill sets. The team’s roles, relationships, expectations, and structure need to be mapped out. Similarly, the team needs to articulate the design process it will use and then communicate this to all members so that they will know when and how they can plan to take part. This often involves the team pretesting its standard procedures—from how data are collected to design generation—to better tailor them to the particularlity of people and place.

ME RELATIVE TO YOU

In addition to getting our initial impulses on the table we need to know the lens through which we see and respond to a place and its people. This lens consists of our values, which are often the root of what impelled us to become designers in the first place. However, our values may or may not mesh with those of the community. There are techniques for drawing out a designer’s own inspirations, personal working style, demographic profile, spatial preferences, and everyday life behavior patterns. Whether you are an experienced designer with many past projects to draw from or a young designer just starting out, part of the unique contribution you bring to a project comes from within.

Once we are clear on who we are, we can see our position in society relative to the cultural and economic context of the community in which we plan to work. This in turn equips us with empathy rather than sympathy. This distinction is important because designers can find themselves in communities with acute needs that have been repeatedly ignored. Although providing technical assistance to a community in need is a critical role of participatory design, responding with sorrow or pity hampers one’s effectiveness. Sympathy, even when it is grounded in understanding, can subtly convey to residents that only the designer’s expertise counts. Another pitfall lies in creating a patronizing process that diminishes the community’s self-worth.

TECHNIQUES TO SUIT UP AND SHED

The techniques in this chapter are about preparation as much as participation. Some are appropriate to undertake every time your team begins a project; some are personal explorations that you will need to work through if you haven’t already done so. In “What’s in It for Us?” Julie Stevens provides a technique to develop a team road map that members can rely on to anchor their involvement. Randolph T. Hester Jr., in “I Am Someone Who,” offers a simple test of the designer’s attitudes and practices to maximize the designer’s effectiveness. Sungkyung Lee and Laura J. Lawson illustrate how a team can explore its assumptions about a locale in “Challenging the Blank Slate.” The technique “Environmental Autobiography Adaptations” provides two alternative approaches to reconnecting with one’s childhood places using self-guided hypnosis and environmental autobiography. In “Finding Yourself in the Census” Marcia J. McNally proposes a simple way to contextualize oneself by working up a demographic profile and then comparing it with similar data on the community. “Consume, Vend, and Produce” allows the designer to identify commonplace and frequently overlooked activities, while recognizing things that are out of the ordinary.

Technique 1.1

WHAT’S IN IT FOR US? DESIGNING A DURABLE TEAM

When it comes to community design, one person can’t do it all—we need teams as dynamic as the communities with whom we work. However, it is difficult to assemble and maintain a team, especially for long-term-engagement projects that evolve in scope and require new inputs of skill and expertise. If you are the leader, you must continually evaluate the needs of the project, the abilities of teammates, and, most importantly, the human connections among members of the design team and community. Because successful teams often form around shared interests and ethics, determining mutual rewards—or team members defining What’s in It for Us—can be a critical technique for developing and managing a team.

Instructions

- In order to understand the expertise, skills, and resources needed, first map out the project. What is the purpose? What will you need to achieve it?

- As the leader with the responsibility of building the team, clarify your own strengths and shortcomings in terms of organization, communication, project management, professional expertise, and so forth. You should know what is motivating you—what is in it for you?

- Make sure you also understand wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Suiting Up to Shed

- Chapter 2: Going to the People’s Coming

- Chapter 3: Experting: They Know, We Know, and Together We Know Better, Later

- Chapter 4: Calming and Evoking

- Chapter 5: “Yeah! That’s What We Should Do”

- Chapter 6: Co-generating

- Chapter 7: Engaging the Making

- Chapter 8: Testing, Testing, Can You Hear Me? Do I Hear You Right?

- Chapter 9: Putting Power to Good Use, Delicately and Tenaciously

- Conclusion

- Contributor Biographies

- Index