- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Who discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls? When and where were they discovered? How were they saved? Who has them now? Will more be discovered? Have all the scrolls been published? Are some still hidden away? Were there conspiracies to suppress some scrolls? How do the scrolls affect Christianity and Judaism? How similar are the biblical scrolls to our Bible today? These and other questions are answered in The Dead Sea Scrolls, A Short History, which offers information from exclusive interviews and unpublished archives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dead Sea Scrolls by Weston Fields in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

DISCOVERY AND PURCHASE

OF THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS

From the left, Muhammed ed-Dib and Jum‘a at the entrance to Cave 1, Qumran. Courtesy of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem

Qumran, Cave 1: 1947-49

The first three Dead Sea Scrolls were accidentally discovered close to the northwest shore of the Dead Sea in a cave near Khirbet Qumran in about January-February of 1947 by three Bedouin shepherds: Muhammed “ed-Dib (the wolf)” Ahmad el-Hamid, Jum‘a Muhammed Khalil, and Khalil Musa. By March, Jum‘a and Khalil had shown the scrolls (the Great Isaiah Scroll, the Habakkuk Commentary, and the Manual of Discipline in two pieces) to several people in Bethlehem: Ibrahim ‘Ijha, George Isha‘ya, and Khalil Iskander Shahin (Kando), the latter an antiquities dealer.

During Easter Week George mentioned the scrolls to the Metropolitan Mar Athanasius Samuel, Archbishop of the Syrian Orthodox Church, who lived at St. Mark’s Monastery in Jerusalem’s Old City. Both George and Kando were members of the Syrian Church. Samuel asked George to contact the Bedouin and find out more about the scrolls. He also telephoned the Syrian merchant in Bethlehem (Kando), and urged him to get the scrolls “by all means.”

By June, Jum‘a and the enterprising George had returned to Qumran, and removed four more scrolls. Three of these (Isaiahb, the War Scroll, and the Thanksgiving Scroll) were eventually, but not immediately, sold for £7 to Faidi Salahi in Bethlehem. Kando later ended up with the fourth, the Genesis Apocryphon (Lamech Scroll).

Anxious to find a buyer, Kando advised Jum‘a, Khalil Musa, and George to present all seven of their scrolls to Mar Samuel in Jerusalem on July 5, 1947, but they were rudely turned away from St. Mark’s Monastery by Fr. Boulos Jilf (Gilf), who knew neither who they were, nor the value of what they carried in their hands. Jum‘a and George took their three scrolls (Isaiahb, War Scroll, Thanksgiving Scroll), Khalil took the other three (Isaiaha, Habakkuk Commentary, Manual of Discipline in two pieces), and, apparently, Khalil gave the Genesis Apocryphon to George and Jum‘a. It would be many years before all seven scrolls were together again in the same place at the same time.

The opening to Cave 1, Qumran. ©John C. Trever

During the next few days Kando agreed to sell the four scrolls held by Jum‘a and George (Isaiaha, Habakkuk Commentary, Manual of Discipline in two pieces, and the Genesis Apocryphon) in exchange for a commission of one-third of whatever he could obtain. Kando accompanied George and two Bedouin to St. Mark’s Monastery, where they left their four scrolls in the care of Mar Samuel. As yet, no one fully appreciated the value of what they had, least of all Kando. Eventually, he would sell these four scrolls to Mar Samuel for £24 (Palestine pounds = US $97.20), saying, “much dirty paper for little clean paper.” Of this amount Kando gave two-thirds, (£16 = US $64.80) to the Bedouin, as they had previously agreed. But in July 1947 neither Samuel nor Kando yet knew exactly what these ancient documents were.

Over the next several months Samuel repeatedly attempted to obtain independent scholarly confirmation of their age and information about their content, with no success whatsoever. He invited two Dominican specialists in Syriac, Frs. Van der Ploeg and Marmadji, to examine the “Big Scroll.” Although Fr. Van der Ploeg identified it as Isaiah (which Samuel had not yet known), neither was a specialist in ancient Hebrew writing styles, so its great antiquity escaped them.

As the hot Palestinian summer waxed strong, Samuel once more sent George, accompanied by the Bedouin, back to the “scroll cave.” They found more evidence of occupation and storage: pieces of cloth wrappings, broken scroll jars, and even one unbroken jar.

Day by day, week by week, Samuel continued to consult various scholars about the age of the four scrolls Kando had entrusted to him. Stephan Hanna Stephan of the Transjordan Department of Antiquities pronounced them “late” (medieval). Some Jerusalem scholars who were invited to look at them didn’t even take the story seriously enough to come to St. Mark’s.

Finally, having given up on the Jerusalem scholarly community, Mar Samuel left on September 15, 1947 for Homs, Syria with Anton Kiraz, another Syrian Orthodox merchant in Jerusalem, as his driver. In Homs he showed the scrolls to Mar Ignatius Ephram 1, Syrian Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch. Like all the others until now, he also doubted their antiquity, suggesting they were no more than three or four hundred years old. The Patriarch advised Samuel, however, to show them to the Professor of Hebrew at the American University of Beirut; but when Samuel arrived in Beirut the Professor was away on vacation.

Back in Jerusalem, Samuel continued his quest. The next visitor to St. Mark’s was a Jewish specialist in Hebrew antiquities, Toviah Wechsler. Although he did not recognize the Scrolls’ antiquity, he did understand their potential value if they were as old as the Archbishop Samuel suspected. “Your Grace,” Wechsler is reported to have said, “if these came from the time of Christ as you imply, you couldn’t begin to measure their value by filling a box the size of this [large] table with pounds sterling.”

By the first week of October nearly six months had elapsed since the Archbishop Samuel had first heard about the scrolls. About this time Kiraz and Samuel became partners in the scrolls in return for Kiraz’s financial support. Like many business partnerships, it was to prove less than fully satisfactory.

The parade of outsiders viewing the ancient documents at St. Mark’s continued. Dr. Maurice Brown, a Jewish physician, made a call to Samuel to discuss the matter of a vacant building adjacent to the Syrian Orthodox School on Prophets Street in West Jerusalem. Since he was Jewish, Samuel assumed that he might be able help date or identify them. While Brown himself could not help Samuel with dating the scrolls, he said he knew someone who could. Samuel later learned that Brown called the President of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Dr. Judah L. Magnes, who sent two men from the University library staff to see the scrolls a few weeks later, probably still in October 1947. “When they came,” Samuel writes, “they spoke Hebrew to each other, and they said that it would be necessary for them to consult their specialist at the Hebrew University before they could make any kind of a statement.” The librarians asked if they could take photographs, and Samuel consented, on condition that they returned and took the photographs at St. Mark’s. They never returned. Brown also sent Yoav Sasson, a well-known Jewish antiquities dealer in the Old City, to Samuel. He suggested, after seeing the scrolls, that Samuel should send them to experts in Europe, but the Archbishop wisely declined.

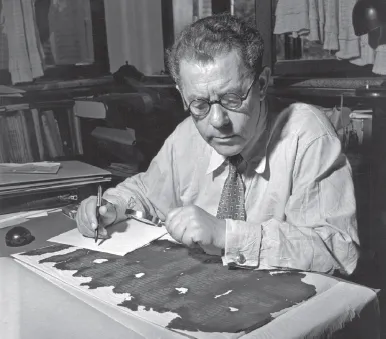

Prof. Eleazar L. Sukenik studying the War Scroll in Jerusalem, 1950. Bettmann/Corbis

More weeks went by. All during August, September and October there had been no word about the other three scrolls (Isaiahb, The War Scroll, and the Thanksgiving Scroll), the ones removed by George and Jum‘a from the “first cave” sometime after the initial discovery. Suddenly parts of two of these showed up in the hands of an Armenian antiquities dealer, Nasri Ohan.

At the beginning of the Jewish work week on Sunday, November 23, Ohan (“Mr. X” in the original account) contacted Prof Eleazar L. Sukenik, Professor of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a specialist in Hebrew epigraphy and the archaeology of ancient synagogues. Ohan and Sukenik were long-time friends. The call to meet once again was unusual only because of the political circumstances at the time. Jerusalem was divided into different areas, and one needed a pass to enter each. Since Sukenik did not have the proper pass they had their meeting across a barbed wire fence at the gateway to Military Zone B.

Through the fence Ohan related that one of their mutual friends, an old Arab antiquities dealer in Bethlehem, had come to him the previous day with a rather strange tale. Some Bedouin had called on this Bethlehem dealer, bringing with them several parchment scrolls which they claimed to have found in a cave near the shores of the Dead Sea, not far from Jericho. These they had offered to sell to him, but the dealer did not know whether they were genuine, nor did he have any idea of what was written on them or how old they were. The Bethlehem dealer had therefore brought samples to Ohan, probably because he knew that from time to time Ohan had sold antiquities to the Department of Archaeology and its museum at the Hebrew University. But Ohan, too, had no knowledge of whether they were really ancient manuscripts or a relatively recent product. He wanted to know from Sukenik whether he considered them genuine, and if so, whether he would be prepared to buy them for the Museum of Jewish Antiquities of the Hebrew University.

As he peered at the samples, Sukenik at first thought they might be forgeries, but then he recognized similarities between the letters on the scrolls and those he had seen on small coffins for bones (ossuaries) which he had discovered in ancient tombs in and near Jerusalem, dating to the period before the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE (AD). He had seen such letters scratched, carved and, in a few cases, painted on stone. But not until then had he seen this particular kind of Hebrew lettering written with a pen on parchment.

It did not take Sukenik long to decide he wanted the scrolls, but ever conscious of maintaining a good bargaining position, he made no indication. He asked Ohan to proceed at once to Bethlehem, bring back more samples, and telephone him when he returned. In the meantime Sukenik would obtain a military pass so that he could visit Ohan at his store and examine the parchments more closely.

Prof. Eleazar L. Sukenik studying the Thanksgiving Scroll in Jerusalem, January 1, 1950. Houlton Archive/Getty Images

On Thursday, November 27, Ohan telephoned to say that he had some additional fragments. Sukenik “raced over” to see him. He sat in Ohan’s store and tried to decipher the writing. He was now more convinced than ever that these were fragments of genuine ancient scrolls. They resolved to go together to Bethlehem to start negotiations with the Arab dealer for their purchase. The next day they intended to go to Bethlehem, but Sukenik’s wife and son, Yigael Yadin, dissuaded him in view of the danger. Later that evening he heard on the radio that the United Nations, expected to vote that day on the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab territories, had postponed its decision. Sukenik believed that Arab attacks would begin immediately after the vote, so he resolved to make the journey the next morning, and this time tell neither his wife nor son. The next day was the Sabbath, but Sukenik and Ohan took a bus to Bethlehem, where they proceeded directly to the home of the antiquities dealer, Feidi Salahi. After considerable bargaining, Salahi allowed Sukenik to take the scrolls home for further examination. Sukenik promised to let him know within two days, through Ohan, whether he would purchase them.

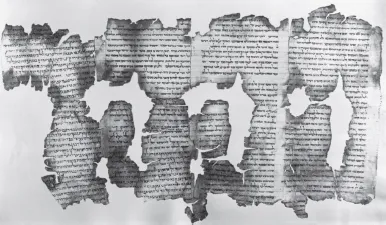

Part of the “Thanksgiving Scroll” (Hodayot) fragment purchased by Sukenik in 1947. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

As soon as Sukenik got home he began his examination, but he could not identify the texts. That evening he called on several colleagues for advice, but none could help. The next morning, Sunday, he was completely certain he would purchase them, but it was Ohan’s day of rest, so it was Monday, December 1, 1947 before he was able to telephone his Armenian friend, and instruct him to inform Salahi that he did, indeed, want the scrolls.

While Sukenik had been examining the scrolls in his study that Saturday night, the late news on the radio announced that the United Nations would be voting on the resolution for the partition of Palestine (November 29, 1947). While he was working, his son rushed in, shouting that the vote in favor of the Jewish State had been carried. As Sukenik later wrote, “This great event in Jewish history was thus combined in my home in Jerusalem with another event, no less historic, the one political, the other cultural.”

Dr. Magnes made available the initial funds needed for purchasing the scrolls. We do not have a record of how, when, or where the money was exchanged, but it was probably sent through Ohan on December 1 or 2.

Shortly afterwards, one of the librarians at the Hebrew University who had seen one or more of the St. Mark’s scrolls happened to see Sukenik and told him about the incident, saying he had tried to follow up, but had been unsuccessful in re-contacting Mar Samuel. Sukenik could not enter the Old City to check this story himself, but a few days later he received a telep...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Isaiah Scroll

- Chapter 1: Discovery and Purchase of the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Habakkuk Commentary Scroll

- Chapter 2: Study and Publication

- Manual of Discipline Scroll

- Chapter 3: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible

- Testimonia Scroll

- Chapter 4: The Dead Sea Scrolls, Judaism, and Christianity

- Rule of the Congregation Scroll

- Chapter 5: Qumran and the Essenes

- Psalms Scroll

- Timeline of Events Related to the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Glossary

- Suggestions For Further Study