- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

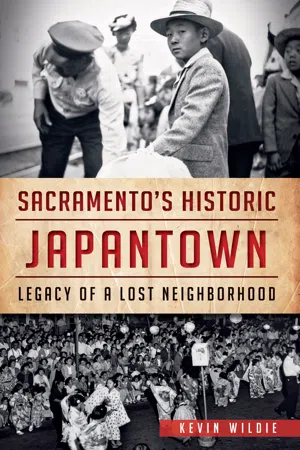

By 1910, Japanese pioneers had created a vibrant community in the heart of Sacramento--one of the largest in California. Spilling out from Fourth Street, J Town offered sumo tournaments, authentic Japanese meals and eastern medicine to a generation of Delta field laborers. Then, in 1942 following Pearl Harbor, orders for Japanese American incarceration forced residents to abandon their homes and their livelihoods. Even in the face of anti-Japanese sentiment, the neighborhood businesses and cultural centers endured, and it wasn't until the 1950s, when the Capitol Mall Redevelopment Project reshaped the city center, that J Town was truly lost. Drawing on oral histories and previously unpublished photographs, author Kevin Wildie traces stories of immigration, incarceration and community solidarity, crafting an unparalleled account of Japantown's legacy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sacramento's Historic Japantown by Kevin Wildie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE SETTLEMENT OF JAPANESE IN CALIFORNIA

AN INTRODUCTION

Japan stood isolated from the rest of the world for over two centuries, until 1854, when the United States forced Japan to open its borders to migration and trade under the Treaty of Kanagawa. At first, the Japanese government permitted only Japanese students and the upper classes to emigrate. As a result of a rapid economic shift away from agriculture to industrial production during the Meiji Restoration beginning in 1868, Japan accumulated a surplus of unemployed farmers and extended emigration rights in 1884 to the laboring and farming classes. Most of these new emigrants served as contract laborers on Hawaiian sugar plantations prior to their settlement on the West Coast. Nearly 30,000 of these dekasegii or “birds of passage” had arrived before the turn of the century. Between 1890 and 1940, some 200,000 Japanese traveled to the United States.1

The first generation of these “birds of passage,” the Issei, concentrated in the West Coast states of California, Oregon and Washington and worked in a narrow range of occupations. In 1920, 65 percent of Japanese emigrants had settled in California, 16 percent in Washington and 4 percent in Oregon.2 By 1930, there were over ninety thousand Japanese in California, a population that comprised 75 percent of the total Japanese population in the United States. More than half clustered in the four counties of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Fresno and Sacramento.3 Although significant, the heavy concentration of Japanese in California is not surprising considering that California represents the area of first major contact for the Japanese immigrants. Like Washington and Oregon, California required manual labor for railway construction and other types of intensive physical work that young, single immigrants could provide. With the passage of anti-Chinese immigration laws after 1882, labor positions that had previously been filled by Chinese were soon filled with ambitious Japanese immigrants. This rapidly developing state also provided conditions that later opened opportunities to engage in economic pursuits to which they were accustomed, such as farming and small business operations.4

Unlike the majority of European immigrants who arrived in family groups, the first wave of Japanese immigrants was predominantly made up of single males, a status that enabled them to accept work as migratory laborers such as lumberjacks, seasonal field hands, farmers, fishermen and laborers on railroads. Although oftentimes risking disease and death from unsanitary conditions and hard work, they could live as bachelors outdoors, in makeshift tents and bunkhouses, and could afford to take lower wages and still save some money to either start a small business catered to their own countrymen or return to Japan.5 The experience of Nisuke Mitsumori, who eventually settled in Sacramento, provides a glimpse of the migratory life of a Japanese laborer in 1905:

On the farm, I was paid only a dollar and a half for ten hours of work, although this was better in San Francisco. The work on this farm was also seasonal. When Strawberry season was over, my work was over, too. Some of us decided to go to Fresno, hoping to get a job there. We thought we could earn three or four dollars, at least, in Fresno, however, we were afraid of getting sick in Fresno since malaria was quite widespread and it was hot there without many trees in those days. Yet, we decided to go…

First, I worked in a vineyard in Fresno. It was so hot that I could not see things on the other side. We started working early in the morning and came back to camp at night, which was just a barrack. It was a terrible place. One morning we got up early as usual, finished breakfast and found that one [in] our group was still sleeping. We tried to wake him up, but found him dead…He worked all day the night before, came back tired, and went to bed. He never woke up. This incident made me aware of a conflict. Making money was fine. But I started to think that it would be meaningless if I died in this struggle.

After that…I worked only in the early morning and late in the afternoon, and took a rest under a fig tree during the day. After I finished work in this vineyard, I went to another vineyard in Fowler…The grape season was over in October. I needed some money to go back to San Francisco. Luckily, I saw an advertisement for railroad men. I immediately became a rail man and went back to San Francisco…From San Francisco I went down to Los Angeles, got on the ship and went to the Gulf of Mexico, came back to San Francisco again, and then took a boat again to Los Angeles. I also went to Fresno in the same year. During this whole year, I experienced a lot.6

Because Japan offered few opportunities for social mobility and financial success, most Issei laborers came to the United States with the hope of becoming rich and then returning to Japan to live a more comfortable life; permanent settlement in North America had little appeal to most of the early immigrants. “In those days two or three thousand dollars meant quite a lot to a Japanese person,” said Riichi Satow of Sacramento. “Anybody coming back to Japan with that kind of money could do whatever he wanted to do—say, build a new house or buy some farmland. This was the dream that most Japanese emigrants had.”7 The desire to learn a trade outside of farming and return to Japan on a greater financial standing motivated James Kubo’s father to travel to the United States. A Nisei (first American-born generation) born in Sacramento in 1916, James Kubo recalled:

My dad and mom were farmers. At that time in Japan the prospect of making money or getting anywhere beyond farming was almost impossible. Once you’re a farmer, you’re a farmer. So when [my dad] was seventeen years old, he had just enough money to take a boat to Hawaii. He worked in the sugar canes until he got enough money to go to the United States. He landed in Seattle and worked on the railroads all over the Northwest. He learned how to cook…and eventually opened up a candy store in Sacramento on Fourth and N [Streets].8

While some did achieve great prosperity—such as George Shima, the “potato king of California,” who established a $17 million farm empire in the California Delta and stands as a classic example of the “Horatio Alger” path to the American dream—the vast majority of the first generation found moderate gains in their financial standing, moving from a wage laborer to self-employment in farming or city trades.9 However, because of growing racial hostility against them and their unfamiliarity with the English language, many found accumulating enough money in order to move from a labor position or tenant farming to independent employment much more difficult than they had anticipated. Frank Hiyama, born in Fresno in 1915, was a child of Issei farmers in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valley. He remembered the racial antagonism and obstacles to financial success that faced most Japanese farmers at this time: “If you were a farmer, you had to buy the farm, had mortgages and hired people to work. The farm usually never made enough money to pay its own mortgage. Very few people made enough money to go back to Japan, including my parents.”10 At age eleven, Hiyama and his family moved to Sacramento’s Japanese American neighborhood near Third and O Streets. A 1911 United States Immigration Commission report substantiates his family’s personal experience:

The race prejudice against them, a prejudice in part due to that earlier exhibited against the Chinese, has prevented their employment in many branches of industry and, in those in which they have been employed, has cooperated with the lack of command of English and of technical knowledge to retard their occupational progress…These limitations upon their occupational advance have placed a premium upon engaging in petty business and farming on their own account.11

Failing to discover their dreams of enduring wealth and good fortune, and unable to save the necessary sums required to make the trip back to Japan, many of the first generation were forced to stay much longer than they had anticipated. Others decided to plant permanent roots in America and exchanged photographs with Japanese women who were willing to marry by correspondence and join their new husbands in the United States. A wave of shashin-kekkon or “picture brides” reached the shores of California in the first quarter of the twentieth century.12 The practice of picture brides emerged as a response to circumvent the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1908, an agreement championed by the racially paranoid Asiatic Exclusion League. This new immigration agreement between Japan and the United States restricted the immigration of Japanese laborers but allowed their wives who were living in Japan to join their husbands in the United States. By 1921, the Asiatic Exclusion League had succeeded in eliminating this immigration loophole for Japanese women and, in effect, sealing America’s borders to all new Japanese settlers. Despite racial exclusionist efforts to prevent Japanese from permanently settling in the United States, the picture bride arrangement fostered a more settled family life. In California, between 1900 and 1920, the ratio of Japanese women to men went from one to seventeen to about one for every two and had almost reached par by 1930.13 In the 1910s and 1920s, Japanese women joined their matrimonial partners, established families and worked alongside their husbands as field workers or domestic aids. Perhaps even more intensely, Japanese women discovered the toil that their husbands had been enduring on the American frontier. Kane Kozono, who helped her husband on their Sacramento Delta farm, recalls those trying early days: “I was young then and could do the hard work. From time to time, however, it was so difficult that I often thought I should have stayed in Japan. I had to cook for a lot of the field hands, too.” Raising children was another added responsibility. She continued:

Frank Hiyama. Courtesy Barbara (Hiyama) Zweig.

When I went to work, I took [my children] with me to the ranch, and I would leave them sleeping under a tree. And when the day’s work was over, I would carry one of them on my back to our home. Men had to work only while they were out in the field, whereas I had to do all of those things besides my share of the work in the field. I did their laundry after work, too. It was a really grueling, hard time for me.14

Apart from such trying difficulties, by 1910, the men and women of the first generation had advanced as farmers, establishing themselves as one of the most skilled groups of agriculturalists in the United States. Some six thousand Japanese families owned or leased more than 210,000 acres in the western states, Texas and Florida. Skill, persistence and optimism, rather than initial wealth, determined the success of most of these family-operated farms. Those families who did rise to the top and become independent farmers were indeed “self-made.”15 Frank Hiyama recalls the older generation’s persistence: “I remember as a child listening to adults talk. I remember one Japanese man who owned a pear orchard and said, ‘One of these days, I’m gonna hit it big!’”16

Uchida family strawberry farm in Florin. Courtesy Japanese American Archival Collection. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, California State University–Sacramento.

The fertile Delta lands along the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers serve as an example of one of the earliest areas of extensive Japanese agricultural activity in California. The farms of the Delta were practically all reclaimed from swamplands by the building of levees and the construction of seepage and drainage ditches. Chinese laborers had cleared much of the land in the 1860s and 1870s for the production of grain, hay and vegetables, all of which went to Sacramento and San Francisco.17 With the availability of better markets, reliable transportation and dependable Chinese labor, farmers began to produce onions, beans, asparagus, celery and deciduous fruits. All of these crops required intensive physical labor in ditch digging, planting, hoeing and harvesting. By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, tenant farmers, mostly Chinese, Japanese, Italian and Portuguese, dominated the Delta, cultivating 9 out of every 10 acres.18 Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, subsequent anti-Chinese immigration laws and the willingness of Japanese laborers to work for less and pay higher rents for land, Japanese tenants came to outnumber the Chinese.19 For example, in 1909, of the 305 tenants who farmed 70,000 acres in the Sacramento Delta, 112 were Japanese, 48 were Chinese, 40 were Portuguese, 60 were Italian and 45 were either Swiss, German, Swedish or native-born whites. Japanese immigrants also occupied the largest share of this land—17,500 acres. An immigration report stated that “for ten years or more the Japanese engaged in work of this kind have been more numerous throughout this large district than all other races combined.”20

The Delta Issei did not achieve their dominant position without their share of pain, misery and sacrifice. Most settled in camps along the Sacramento River in the small farm towns of Clarksburg, Freeport, Courtland, Pearson, Walnut Grove, Isleton, Grand Island and Sutter. Within these camps, malaria and typhoid fever were rampant, living quarters were poorly constructed and the furniture was cheap, crude and inadequate for comfortable living. Oftentimes, especially during harvest seasons, overcrowded housing forced some to find shelter in barns with horses and cows. One report stated that thirty-six Japanese laborers were occupying an eight-room house. In another instance, sixty-one were occupying an eleven-room house.21 Further, the Delta offered few opportunities for a social life. Access to the small, dilapidated churches, schools or bar rooms near the little villages at boat landings remained difficult. The absence of wagon roads and bridges forced travelers to use ferries and steamboats, both of which required money. “We didn’t have any recreation at all,” said Osuke Takizawa, a Delta farmer who settled in Sacramento. “If you wanted to go to town, you had to travel 40 miles to Sacramento on a river boat. The river boat was the only transportation.”22 An immigration agent added, “The older ranchers have tended to move away from their ranches to other places where as a result of 40 years of progress, normal living is possible, as it is not for the ordinary farmers residing on the Delta lands.”23

Searching for more comfortable living and employment during slower periods of the season, Issei laborers traveled either south to Stockton or back up the river to Sacramento. In Sacramento, seasonal laborers found comfort in Japanese-owned lodging, bathhouses, saloons, billiard halls and provision stores. Authentic Japanese meals an...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Settlement of Japanese in California: An Introduction

- 2. The Rise of Japantown in Sacramento, 1890–1940

- 3. Sacramento’s Japanese American Community and Forced Evacuation, 1941–1942

- 4. Postwar Resettlement, Urban Redevelopment and the End of Japantown, 1945–1960

- 5. Conclusion

- Appendix. Sacramento’s Japantown Business Establishments, 1940

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author