- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

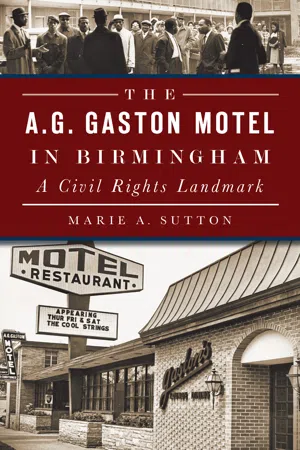

The A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham: A Civil Rights Landmark

About this book

Traveling throughout the South during the 1950s was hazardous for African Americans. There were precious few hotels and restaurants that opened their doors to minorities, and fewer still had accommodations above the bare minimum, to say nothing of the racism and violence that followed. But in Birmingham, black entrepreneur and eventual millionaire A.G. Gaston created a first-class motel and lounge for African Americans that became a symbol of pride of his community. It served as the headquarters for Birmingham's civil rights movement and became a revolving door for famous entertainers, activists, politicians and other pillars of the national black community. Author Marie Sutton chronicles the fascinating story of the motel and how it became a refuge during a time when African Americans could find none.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham: A Civil Rights Landmark by Marie A. Sutton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

LOCKED OUT, BUT CREATING A NEW WAY

I couldn’t understand why the color of your skin made you better than me. That didn’t make sense.

—Brenda Faush, a native of Birmingham, Alabama

Alabama’s scorching summer days do not discriminate. Beneath the merciless sun, there is neither black nor white, rich nor poor—the warmth oppresses all. From the pristine streets of Mountain Brook to the dusty roads of Acipco-Finley, the thick, humid air can be suffocating and the pavement like hot lava.

If your skin is brown, however, it doesn’t take long for a million little reminders—like needle-thin icicles—to prick you back into reality; not even the indiscriminate Alabama heat can thaw out cold hearts or melt away the blistering, blue knuckle winter of segregation.

During the 1950s—in the sweltering June, July and August months—a Negro child had to still any excitement at the site of Kiddieland Park.1 Riding along the endless stretch of Third Avenue West in Birmingham, the fairgrounds could be spotted from the road. The smell of salty, buttered popcorn and sweet, airy cotton candy was a seductive lure. The bright, colorful Ferris wheel sliced through the skyline, and the grounds danced with spinning boxcars, mock airplane rides and a merry-go-round.

Kiddieland was an annual summer carnival that was created in June 1948 for area children. Described by the Birmingham News2 as a “miniature Fairyland,” it was touted as “welcome to all,” though it was understood that that meant everyone except Negroes. The fair featured Sunday concerts, “hillbilly” shows, a “pint-sized edition of the Southern Railway’s Southerner” train and advertisements that showed rosy-cheeked children drunk with glee. It was not until years later that blacks were allowed to come, but only on the last day when the stuffed toys were usually picked over and nearly gone; the vendors were packing up and the popcorn stale.

Kiddieland. Courtesy of Tim Hollis.

Little Southerner miniature train. Courtesy of Tim Hollis.

Ask a room full of blacks who grew up in Birmingham during that time, and only a scant few won’t mention how their memories were stained by not being allowed to attend the fair.

“I remember looking over there and knowing that I couldn’t go and not quite understanding why,” remembered Samuetta Hill Drew, who was a colored child in Birmingham during the 1950s.

Tamara Harris Johnson’s parents tried to shield her from the Kiddieland discussion, she said. Even though the street on which the fair sat was a main artery to downtown, her parents, and many others, found alternative routes so as not to explain why admission to the fair was more than a dime. It also required that your skin be white.

That was the way it was in Birmingham. If you were black, you were only given access to scraps of the American dream; the torn and tattered pieces, the chewed up and spit out ones. Jim Crow laws made sure of it.

City ordinances3 deemed it illegal for blacks and whites to play cards together or even enjoy movies collectively unless there was separate seating, entrances and exits. And the only way they could eat in the same room was if they were divided by a solid partition that reached at least seven feet from the floor. Signs that read “whites only” hung on doorways and water fountains throughout the city. Even the telephone directories noted whether people or businesses were “C” or “Colored.”4

At downtown department stores, blacks were not allowed to try on clothes. They had to guess their sizes, buy them off the rack and hope they would fit. If black customers needed new shoes, many would trace their feet on pieces of cardboard at home. Then, at the store, they would hold the board against the bottom soles until they found a match.

Even conventional elevators were off limits. Whites rode the ones in the main area, while the ones in the back were for “niggers and freight.”

At the same time, however, blacks built their own communities that were fortified with pride and sustained by unity in spite of outside forces. Smithfield in central Birmingham was the largest black middle-class community.5 It was populated with affluent and college-educated African Americans. Many were teachers, lawyers, musicians and doctors. They lived in large Colonial Revival–, Georgian-, Craftsman-or Bungalow-style homes, many of which were designed by Wallace Rayfield. He was the second formally educated and practicing African American architect in the nation at the time and was also a Smithfield resident.

Blacks of every profession lived within blocks of one another, said George A. Washington, who grew up in the area. He remembers a laundry list of them within a stone’s throw, including the doctor who lived across the street and did house calls. “We had everything we needed,” he said.

Neighborhood children played on manicured lawns in a part of the city that seemed untouched by the crippling Jim Crow. That is, until the Ku Klux Klan planted the occasional bomb, blowing off sides of residences or leveling abodes to smoldering bits; enjoying the Smithfield community came at a price.

In 1947, acclaimed African American civil rights attorney Arthur Davis Shores helped Samuel Matthews, a drill operator, file suit against the city for its racist zoning laws that restricted blacks in where they could live. Matthews had his sights set on living in the all-white North Smithfield. He became the first African American to purchase a home in that area. On his first night there, however, his home was bombed.

Shores continued his fight against the zoning ordinances and, in 1950, successfully filed suit on behalf of Mary Means Monk. The age-old racist ordinance was declared invalid by Judge Clarence Mullins. It was a victory. That same night, though, Monk’s home was bombed.6 Pretty soon, the area got the nickname “Dynamite Hill.”

A few miles away, in North Birmingham, sat Collegeville and Acipco-Finley. Many blacks who lived there were blue-collar workers with cracked hands and soft hearts. They lived in an area that sprouted out of housing developed for the employees of Sloss-Sheffield Corporation, Southern Railroad, U.S. Pipe, Jim Walters Corporation and GATX Tank Corporation.7 Instead of playing among a row of Colonial-style houses, the children in parts of the area played among railyards and old coal cars beneath gray skies laced with sulfur and where the whistle of passing trains filled the air.

They weren’t spared the hand of the Klan, either. Their homes, and even churches, were being bombed just like in Smithfield. Nothing a Negro owned or loved was ever not at the mercy of a dynamite-wielding klansman.

Many of the residents of Collegeville, Smithfield and the like worked and owned businesses in the historic Fourth Avenue Business District, which was a thriving, bustling area. Strict segregation laws kept blacks out of certain parts of downtown, and a line of demarcation outlined the area. East of Eighteenth Street North was for whites only, while west of the line toward Fifteenth Street was for blacks. Every inch of the Fourth Avenue District was populated with black-owned businesses like printing shops, restaurants, beauty salons and law firms. All the parties, shows and social club soirées were likely held somewhere in the area.

The seven-story Colored Masonic Temple was a showpiece in the district. The brick and limestone Renaissance Revival–style building was erected by the black-owned Windham Construction Company and featured a grand ballroom where concerts, dances and society events were held. When the white community invited a big-name African American artist to perform at one of its venues, black promoters would often invite that same artist to stop by the Temple to perform for a crowd of their own people.8

A few streets over, the Alabama Penny Savings Bank was a source of pride. It was the first black-owned and operated financial institution in Birmingham and was housed in the six-story brick Pythian Temple that was also constructed by the Windham Company.9 The bank financed the construction of homes and churches of many blacks during that time, according to the National Historic Register.

During the day, the area swelled with people darting in and out of buildings, doing business, having lunch and making social calls. “It was the hub of the city for African Americans,” Drew remembered.

At night, the streets within the district were nearly busting with folks dressed in their Sunday’s best. People packed into the Carver and Famous Theaters, as well as countless restaurants, poolrooms and dancehalls, including the Little Savoy Café, which was built in the style of New York’s Harlem Savoy Ballroom. The upstairs kitchen produced an endless supply of mouthwatering chicken and steak dinners, and downstairs in the hall you could catch performances by Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton and many others.10

“I used to love the way they dressed, like in a movie, like Harlem Nights,” said Washington, who as a young man would try to go inside the area nightspots. “We would go in, peep in the door and they would put us out.”

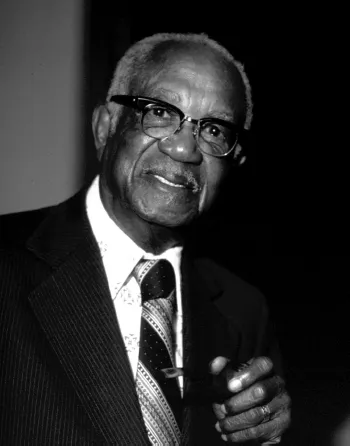

During that time, the black middle class was growing at a rapid pace. The community roster grew long with names that would later be in history books like Attorney Arthur Shores, famed deejay Shelley “The Playboy” Stewart and business mogul A.G. Gaston. Gaston was a short-statured, chocolate-brown man who had a penchant for dapper dress and a stern business sense.

“He always wore three-piece suits with a little watch chain,” wrote civil rights icon and former United States ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young in his book An Easy Burden.11

A.G. Gaston. Photo by Chris McNair of Chris McNair Studios.

“He was the very image of dignity and wealth,” Young wrote, “except for his brown skin.”

Gaston, who had only a tenth-grade education,12 made millions catering to the needs of blacks, a clientele that was often ignored by white business owners. He owned funeral homes, a bank, an insurance company and a radio station; hosted spelling bees for colored children; and founded a girls’ and boys’ club. He was known for servicing African Americans from the cradle to the grave and advertised his businesses as “strictly 100 percent Negro.”13

“He was the most powerful man in Birmingham,” Washington said. “What he said was the rule of the day, and he generally got what he wanted.”

GASTON WAS BORN IN a log cabin in Demopolis, Alabama, on the Fourth of July 1892. His father, “Papa” as he was known, died seeking work with the Alabama Great Southern Railroad construction project,14 and his mother, Rosie, was a beloved domestic who cooked and cleaned for A.B. and Minnie Loveman, one of the most affluent white families in the area. The Lovemans owned the popular Loveman, Joseph & Loeb Department Stores.

Born a generation out of slavery, Gaston grew up knowing his place as a black man living in the South. He wrote in his biography, Green Power:

Any “nigger” who did not jump off the sidewalk when they came by was considered “biggity” by the whole community, and just not well brought up. Most of the civic leaders and professional men were members of the Klan…So, when as a boy I watched a lynching on the street corner, there was no doubt in my mind justice prevailed and that the punishment was surely deserved.15

The Jim Crow way of life did not totally cripple Gaston’s family, however. His mother at one time ran a catering business with clients who included some of Birmingham’s wealthiest white families.16 Gaston’s grandparents Joe and Idella were born slaves but, after being freed, became business owners who taught him a strong work ethic.

Gaston’s first business, down in Demopolis, was selling rides on his family’s tire swing. As a young boy, he charged the neighborhood kids a button to ride and ended up with a coffer full.

In 1905, at age thirteen, Gaston mov...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Locked Out, but Creating a New Way

- 2. A Feather in Birmingham’s Cap

- 3. A Place for Us

- 4. Where Trouble Sleeps

- 5. First Class All the Way

- 6. Enough Is Enough

- 7. And a Child Will Lead Them

- 8. The Last Straw

- 9. Music in the Air

- 10. Out of Place

- Timeline

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author