- 117 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Iroquois Crafts

About this book

There is nothing more colorful in the North American Indian history than the story of the League of the Iroquois. An Iroquois Indian crafts manual with photographs, and drawings of examples, historical background, patterns of clothing, bark utensils and decorative arts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Iroquois Crafts by Carrie A. Lyford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1—HABITAT

VILLAGES

The Iroquois were a hunting, fishing and agricultural people, living in compactly-built villages consisting of from 20 to 100 houses built on high, level tracts of land or on buffs removed from streams or lakes, surrounded by small vegetable gardens, orchards, and cornfields often comprising several hundred acres.

About the period of the formation of the League (1570), the villages were enclosed by a single or double row of palisades or stockades erected to protect the inhabitants from attack by hostile tribes. The stockades were made of 15-foot logs, sharpened at one end and set in a continuous row in an earth embankment. In a description in his travels (1535) Ramusio tells of a strongly palisaded Iroquoian town known as “Hochelaga” consisting of 50 houses, each built with a frame of stout poles covered with bark. About 3,600 people inhabited the village.

The necessity of stockading the villages had almost ceased by the beginning of the seventeenth century, and by the close of the century the stockades were abandoned. Villages became less compact, but houses continued to be built near enough together to form a neighborhood.

It was sometimes necessary to change the village sites. The bark houses decayed and became infected with vermin, accessible firewood became exhausted, and the soil ceased to yield freely. Much work was involved in moving to a new site and building up a new village.

THE LONGHOUSE

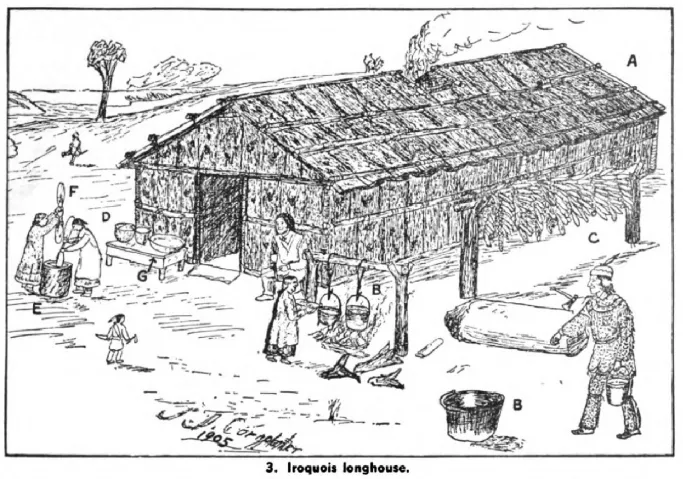

The characteristic dwelling of the Iroquois was a log and bark community house known as the longhouse (ganonh’sees) designed to accommodate five, ten, or twenty families. The longhouse ranged in length from 30 to 200 feet, in width from 15 to 25 feet, and in height, at the center, from 15 to 20 feet. The average longhouse was 60 feet in length, 18 feet wide, and 18 feet high. It was built with a framework of upright posts with forked tops. The lower ends of the posts were set one foot into the ground to form a rectangular space the size of the building to be constructed. Horizontal poles were tied with withes to the vertical poles, along the sides and across the tops. A steep triangular or rounded roof was formed by bending the slender, flexible poles toward the center above the space enclosed by the poles.

The framework of logs was sheathed with bark. The bark was gathered in the spring or early summer up to mid-July. Slabs of bark 4 feet wide by 6 or 8 feet long were removed from the elm, hemlock, basswood, ash, or cedar trees. The elm bark was considered best. The bark was pressed flat under weights, and laid horizontally over the framework of poles, the slabs of bark overlapping one another like shingles. Basswood withes or strips of bast from the inner bark of basswood and hickory trees were used to fasten the pieces of bark together and to secure them to the framework. Holes for use in sewing were made in the bark by means of a bone puncher.

A series of poles, corresponding to the poles of the framework, were set up outside the bark, and close to it, on the four sides and across the roof. They were tied to the first set of poles, binding the bark firmly in place. No metal tools or commercially manufactured materials were used in the erection of the longhouse.

The longhouse had no windows, light came from the high, wide doors at each end, and from above. A movable piece of bark or tanned hide, which could be easily tied back, was used as a door, of the entrance. In the roof were square openings to admit light and to allow for the escape of smoke. Pieces of bark were provided on the roof to close the holes when wind, rain, or snow made it necessary. They could be controlled from within by pushing with a long pole.

A central hallway from 6 to 10 feet wide ran lengthwise of the longhouse. The hallway served as a place for social visiting where children played while their elders reclined on the mats of reeds and husks provided for the purpose.

Raised 18 inches from the ground along the two sides there ran a series of compartments or booths to accommodate family groups. The booths were from 6 to 12 feet long and from 5 to 6 feet wide. They could be curtained off with skins so as to give privacy at night. Each compartment belonged to a given family and was not to be violated by members of other families. Private ownership existed, though life was carried on in a communal way. Platforms about 3 1-2 feet wide, running along the sides of the booths, provided bunks for sleeping. Small bunks were sometimes built for the children. Several layers of bark, reed mats, and soft fur robes covered the platform. About 7 feet from the ground a second platform was erected over the bunks, to be used for storage. Cooking utensils, clothes, hunting equipment, and other possessions were stowed away wherever a place could be found for them. Pits were often dug under the beds for the storage of household treasures. On the cross poles or rafters were hung large masses of dried corn (united by braiding the husks of the ears together), strips of dried pumpkin, strings of dried apples and squash, herbs, and other supplies.

At each end of the longhouse, storage booths and platforms were provided for the food that was to be kept in barrels and other large containers.

Down the central passage, between the booths, rough stone fire places were arranged to provide fires for comfort and for cooking, and for light at night. One house might have as many as 12 fires. Each fire place served two families. The fire built by the Indian was always a small one, not like the White camper’s roaring bonfire.

During Revolutionary times the bark house of the Iroquois was fitted up with sturdy furniture. Corn husk rugs were used on the floor. Splint baskets, gourd containers, skin bags, and other handicraft products were among the furnishings. Braids of sweet grass were sometimes hung in a house to decorate and perfume it. A strong, straight bough or a thick board that had been deeply notched up one side served as a ladder to facilitate climbing to the high platform and the roof. The windows were barred with small boughs. The tong-house continued in use up to the eighteenth century after which time it was gradually abandoned. At Alleghany it was used up to 1800.

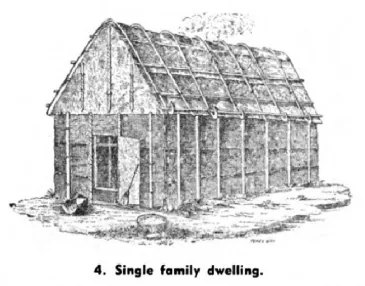

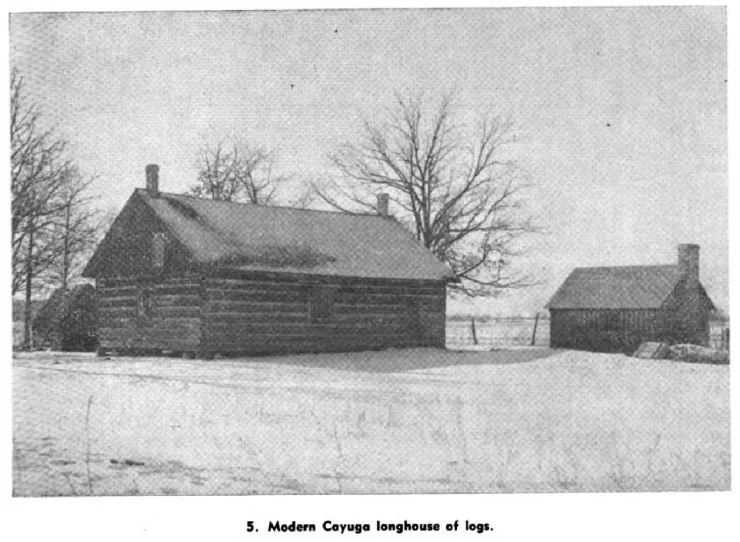

During the seventeenth century a house of logs and elm bark about 20 feet long had come into use for the single family. About the end of the century this was supplanted by a house of white pine logs, which is still used to some extent as a place for storage. Today the home of the Iroquois duplicates that of his White neighbor of the same economic status. Small frame houses predominate on the reservations.

In the old days a small dome-shaped hut about four feet high and six feet in diameter was built of bent saplings to be used for^ the sweat bath in the summer time. It did not disappear until some time in the nineteenth century. Heated stones piled in the hut were covered with water poured from a bark receptacle and clouds of steam surrounded the bather, producing a cleansing sweat. The bather then was rubbed with sand, and plunged into a nearby stream.

2—FOODS

SECURING AND PREPARING

Among the Iroquois the women did the gardening; the men were the hunters. In the early days the Iroquois made much use of both fresh and dried fish and meat. The many lakes and streams of the Iroquois country yielded an abundant supply of fish during the spring fishing season. During the season of the fall hunt, long and toilsome expeditions to secure game were undertaken by the men. When times of scarcity occurred the Iroquois found it necessary to supplement the larger game by adding the meat of many of the smaller animals to the diet. In the old village site bones have been found of bison, deer, elk, black bear, porcupine, raccoon, martin, otter, woodchuck, muskrat, beaver, skunk, weasel and dog. Domestic pigs, geese, ducks, and chickens became sources of food after their introduction into Quebec about 1620.

After the formation of the League, when the Iroquois became settled in more permanent villages, their food supply shifted more and more to an agricultural basis, and agricultural products came to form the major portion of their diet.

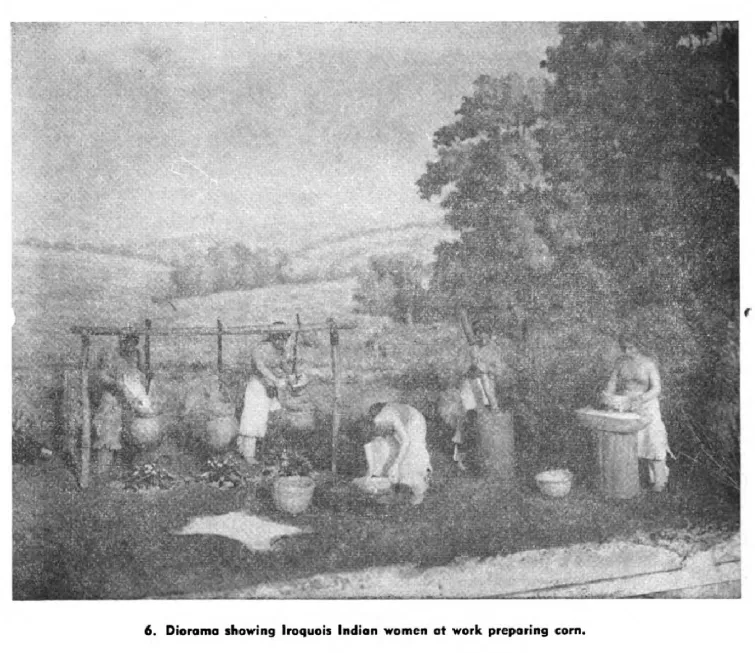

The entire process of planting, cultivating, harvesting, and preparing food for the family was in the hands of the women. A chief matron was elected to direct the communal fields, each woman caring for a designated portion. Certain fields were reserved to provide food for the councils and national feasts. Ceremonies were observed and special songs were sung at the time of planting and harvesting. Sacrifices of tobacco and wampum were made to the food spirits.

Through a mutual aid society, in later years known as a “bee,” the women assisted one another in their individual fields when planting, hoeing, and harvesting. They laughed and sang while they worked. Each woman brought her own hoe, pail, and spoon. When the work was over a feast was provided by the owner of the field, and everyone went home with a supply of food, usually corn soup and hominy.

Corn (Maize) has always been the principal food of the Iroquois. Corn pits have been found at old village sites. Even before the formation of the League...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- MAP

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1-HABITAT

- 2-FOODS

- 3-CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES

- 4-SECRET SOCIETIES AND CEREMONIES

- 5-GAMES AND SPORTS

- 6-ANCIENT CRAFTS OF THE IROQUOIS

- 7-DECORATIVE ARTS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- IROQUOIS QUILL DESIGNS