![]()

Part I—El Salvador in Context

1—Prone to Violence

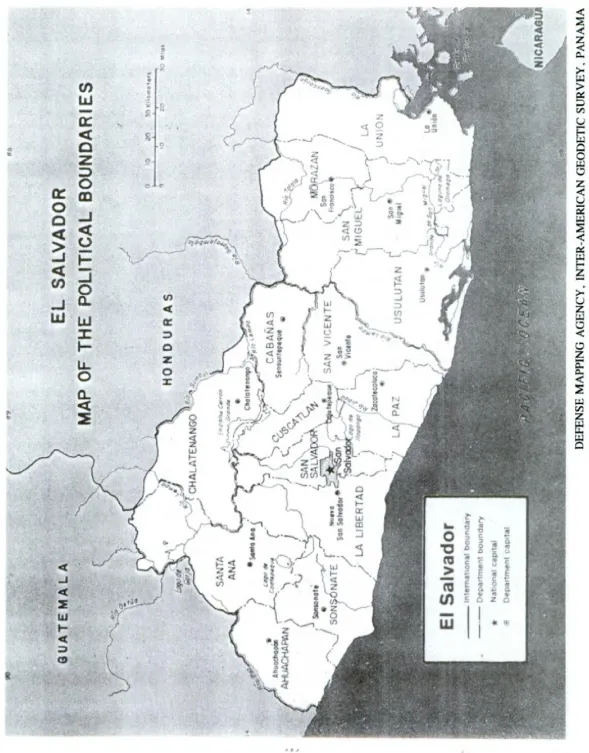

THE EDITORS—To counter a revolutionary strategy aimed at a Third World social order, the first priority is to understand it. An appreciation for the causes of a specific environment and the primary center of gravity form the basic foundation for that understanding. In this context, the struggle in El Salvador needs to be understood as it appeared to the three primary players—the insurgents, the Salvadoran government, and the United States.

The root causes lay deep within the history of Latin America, and for the insurgents, the “revolution” had its root causes in social injustice and had been going on for at least a decade prior to October 1979. They saw it as a long-term violent struggle which must totally displace the existing order. Likewise the new political elites, brought to power by a coup, wanted to use the existing governmental structure to implement reforms and saw the need for a “revolution” which created—again over a long term—a more representative governance, one capable of correcting the social and economic injustices. The United States, as the third major actor, saw the conflict as a follow-on to the regionally unsettling, anti-U.S. takeover in Nicaragua. The United States wanted to calm the situation, sought a return to normalcy, but had no plan or long-term objectives.

No Strong Basis for Democracy

General John R. Galvin—The root causes go back 400 years. First of all, there was never any franchise for the indigenous people in Central America and indeed in most of Latin America. While every country is different and Latin America is not a homogeneous unit or organization, the so-called revolutions of Latin America were the revolutions of the Spanish elite to free themselves from Spain, in order that they could do whatever they wanted to do in running the governments. The neglect for the indigenous person is obvious in the fact that the indigenous peoples, even today, are pushed up into the mountains, into the less productive areas, and have very little to say about what goes on in the countries. So, the revolution, in effect, never came. The gnawing background that is there is the elitism. Really, I believe there is a great deal to what the historians say about the old civilizations, such as the Toltecs, the Aztecs, the Incas. They were more collective civilizations. True, the priests were an elite. But, there was greater involvement of the masses at that time than there is now. The Spanish Conquistador outlook is still reflected in the elitism that you see in many of these countries. There was not the same desire to bring the country itself ahead. There was more of a “what’s in it for me” attitude in a lot of these people. I realize that’s a strong accusation, but it is one that I think is supported by history. Now, in addition to that, you had governmental infrastructures which were extremely weak. They did not extend out into the provinces. They were basically concerned with agriculture and industry, such as it was—mining, and so forth—in the countries. So, a combination of lack of franchise for indigenous peoples and extremely weak infrastructures gave a comparatively greater strength to the church and the military and those allied with the administrations, one after the other, in those countries. These conditions did not provide a kind of strong foundation for democracy. These weaknesses remain in the background. Now, it is the move of the disenfranchised people and the reaction to that by the elites that has a lot to do with the problems in Central America.

General John R. Galvin, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Southern Command. 1985 to 1987, interviewed in Mons, Belgium, 18 August 1987.

A History of Minority Governments

Guillermo M. Ungo—The struggle for democracy in El Salvador has a long history. Its fundamental causes are internal, but since the conflict’s beginnings, its course has also been affected by a powerful external force, the government of the United States.

The oligarchic-military governments of El Salvador have long kept in place unjust institutions and policies that have excluded the majority of the people from real participation in the decision-making processes that affect their social, economic, and political life. Democracy has become a cruel and painful deceit to Salvadorans; its practice is considered dangerous and subversive. Any statement favoring social change provokes violent retribution as a matter of course. The social doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church and the other churches, the exercise of trade-union rights and of freedom of thought, and criticism of the government are perceived to serve international communism.

The consequences of this way of thinking are clear. Church leaders are persecuted, unions are destroyed, and opposition newspaper offices and radio stations are dynamited. More than 40,000 Salvadorans have been murdered since 1980, including reporters, teachers, students, professionals, political leaders, an archbishop, and priests, in addition to thousands of workers and peasants. Thus the practice of democracy in El Salvador has a history written in blood.

Making a mockery of Abraham Lincoln’s ideals, El Salvador’s rulers have created governments of the minority and for the minority whose survival has depended on institutionalized violence, on closing the channels of democratic participation, and on ever-increasing violations of human rights. Over the years, the dispossessed majority and the political, social, and religious leaders have faced a dilemma: To fight back and risk death in resistance or to submit and risk death from hunger, poverty, or political repression. It is not possible in El Salvador to aspire peacefully to human rights and political freedoms; their pursuit is a reckless venture. This is the true cause of the present war.

(Political leader of the FPL) Guillermo M. Ungo, “The People’s Struggle,” Foreign Policy 52. (Fall 1983), p. 51-52. Copyright 1983 by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Reprinted by permission of Foreign Policy.

Live with the System or Become Part of the Fertilizer Program

Colonel John D. Waghelstein—The Salvadoran system (prior to the coup) was not designed to solve the problems of the campesino dating back 50 years, or even longer if you go back before the Matanza. It was designed to keep the lid on, and if the campesino didn’t like it, he had a couple of options: You could emigrate or you could become part of the fertilizer program. There wasn’t any mechanism for grievances that worked. You were at the mercy of the landowner and the military in cahoots.

The Political Spectrum

Ambassador Thomas Pickering—I would say you had in the political structure, first, the organized parties. You had, over on the extreme left, the Communist party and its more radical offshoots. A good reason why the guerrilla organizations developed in the first place was that the Communist party for a long time hewed to the Moscow line of a broad political front but no armed action. So some of the original guerrilla groups split off because they believed in armed action. You had them joined by some of the church reformers in the late sixties and seventies, who became more and more politically radicalized and as a result found it easier and more compatible to join the political wing of the armed resistance. Moving closer to the center, you had the Social Democrats and the left of the Social Democrats. Some of them, along with the left of the Christian Democrats, joined the guerrilla organizations in 1979 at a time of major upheaval when it didn’t look like the political situation would improve, and they felt sort of trapped out there. Some of them, I understand, now want to come back in out of the cold.

Colonel John D. Waghelstein, Commander, U.S. Military Group in El Salvador, 1982 to 1983, interviewed in Washington, D.C., 23 February 1987.

Ambassador Thomas Pickering, U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador, 1983 to 1985, interviewed in Tel Aviv, Israel, 25 August 1987.

Among the political front of the guerrillas, there were some people who were genuinely Social Democrats and some people who were pretty much radical Communists in one guise or another. Further over you have the broad range of Christian Democrats, some of whom are conservative and some of whom are fairly liberal but occupying a center and left of center position. Right center was the PCN, Partido de Conciliación Nacional (National Conciliation party). The old party of the aristocracy, which was trying to find a way to reform its own image, and its right-wing offshoot ARENA (National Republican Alliance). And to the right of ARENA you had people who were basically only semi-political managers of death squad activities, some of it for political reasons, some it for economic and commercial reasons, some of it just to try to control labor, to keep the campesinos under their thumb, and to maintain some tranquillity in their village or whatever it was. You had a strong attraction in the rural population, interestingly enough, for authoritarianism of the Right because it was traditional, because they knew nothing else. You had, of course, the spectrum to the left of the Christian Democratic party flirting with the guerrillas from time to time.

The major campesino organizations, which had been radicalized by the political processes leading up to the ‘79 overthrow of Romero, the Junta, and all the things that came out of it, were influenced by the AFL-CIO on the one hand and the guerrilla organizations on the other, constantly competing for their loyalty and support. That’s the political spectrum. Within the social spectrum certainly there were the wealthy land-owning families, a large share of which had left, but the remnants of which were generally allied with ARENA, though not entirely. There were exceptions, people who would support other parties that in their total political views shared their deep resentment over the changes that had so affected them in their lifestyles. They weren’t really affected all that much, but with their insecurity they were very difficult to deal with, and they ran the gamut in their power and influence. Then you had people who supported the PCN for traditional reasons, who were more open to democratic arguments and wanted to give themselves a new image, and you had people who were blatantly and openly ARENA, vocally anti-Communist. Fear of communism justified a lot of other things on their part. Not all of them were necessarily bad actors, but many of them were extreme nationalist Salvadorans who felt that the old system and the good old days were not yet over. They were definitely afraid of the Communists and the radicals or those who had been hurt one way or another by the violence of the country. You had to understand that the country itself was an extremely violent country. We looked back at world statistics in 1967, at one time, for civilian death rates, and we found that Salvador was right behind Aden in those days, and, of course, that was a period of war in Aden when the South Yemenis were trying to get rid of the British. It was true, it was a society heavily prone to violence. In large measure, alcohol, the machete, lack of education, frustration, all tended to produce a certain atmosphere of Saturday night massacre in the place. It was often violence simply for reasons of quarreling. Violence and alcohol were familiar ways for people to find respite from the other difficulties of life in the country. Violent methods of control were a part of the repressive atmosphere, and this was very much looked on as normal by people on the Right.

Aside from all these, you had within the country a well-educated class of individuals, a growing middle class, whose political views covered a spectrum. The Christian Democratic leadership in large measure had been influenced by American education and values and by European education and values. They considered themselves intellectually respectable. You had, in the universities, strong centers of leftism particularly among the academics and the tradition of the free university of Latin America. And in a sense the major leadership of the guerrillas, in an intellectual sense, was drawn from the universities. They were a combination of university drop-outs—not that they were intellectually unable but, rather, people who were products of a radical university system—plus campesinos and peasants, pressed into the organization and pushed by them, plus priests and other individuals who grew out of the Catholic reform movement. That’s basically the kind of spectrum you had to deal with in the country. Some technocrats, 500,000 internal refugees, and 500,000 external refugees.

![]()

2—Revolutionary Change and the Role of the United States

THE EDITORS—In February 1972, after a decade of political struggle to work within the electoral process, the center-left National Opposition Union (UNO) was declared the winner of the national election by the Central Election Board of El Salvador. Napoleón Duarte was to be the first president and Guillermo Ungo the first vice-president in 40 years who were not the handpicked candidates of the landed oligarchy and the ruling military. Immediately following the board’s announcement of UNO’s victory a news blackout was imposed, to be lifted three days later when the Election Board announced new results. The military-backed National Coalition party (PCN) was declared the winner with Colonel Arturo Molina as president. Soon thereafter Duarte was implicated in an abortive coup attempt. He was forcibly taken from the Venezuelan Embassy, beaten, and put on a plane to Guatemala, from where he went into exile in Venezuela. This overt subversion of the election process created political turmoil. The legitimacy of the government was eroding, and the opposition political parties began to look for alternatives to the election process to bring about change.

Satisfied with maintaining the status quo, the oligarchy, fully in charge of the economy, looked to the military to maintain order and to protect their interests. With the oligarchy’s continued seemingly total inflexibility to change, coupled with growing social unrest and political turmoil, the military government under Colon...