![]()

PART 1

Questions of Method

![]()

1

JUSTIFICATION, DOUBT, AND PROTEST IN SIXTH-CENTURY BIBLICAL LITERATURE

Bringing justification, doubt, and protest together under the unifying rubric of “theodicy as discourse” requires a discussion of each of these terms individually and a study of the ways they operate in relation to one another in Hebrew Bible texts. I begin by assessing some classical scholarly definitions of theodicy that shaped the way that the biblical evidence is traditionally understood, and I adapt Ronald Green’s conceptual model of the “problem of theodicy” to map the biblical deliberations. The individual phenomena of justification, doubt, and protest are viewed through the analysis of two biblical examples, Jer 21:1–7 and Lam 2. Both texts have something to teach us about the limits of current definitions of theodicy for understanding these texts and the world that produced them; both texts demonstrate the need to expand or revise prevailing scholarly conceptions about theological reflections in Hebrew Bible texts. There are, however, risks inherent in superimposing alien categories onto the biblical thought-world and suggesting theodicy as discourse as an alternative framework for Hebrew Bible theology.

1.1. THEODICY: JUSTIFICATION OF A JUST GOD

1.1.1. Scholarly Definitions and Their Legacies

The foundations of modern discussions of theodicy in the Hebrew Bible were laid by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who coined the term in 1710; in so doing, he opened the door to two quite different understandings of its meaning. The construction, which brings together θεός and δίκη, may stand simply for “God’s justice.” For Leibniz, theodicy appears to constitute the argument that God rules his world with justice, that he is a just judge, particularly in the face of human suffering. But theodicy may also stand for “the justification of God” in all God’s roles and actions, limited neither to the single role as a judge nor to the sole arena of justice. Philosophical and theological discussions since Leibniz draw on both meanings, although Hebrew Bible texts allow us to distinguish between them.

Walter Brueggemann writes: “‘Theodicy’ is the ultimate, inescapable problem of the Old Testament (even though the term is never used).” Indeed, within the thought-world of the Hebrew Bible, theodicy may be seen as a framework for the reformulation of religious thought in times of crisis; it seeks to account for the existence of evil and human suffering in a world that the believer assumes is conducted by God, the lord of history, according to just principles.

Theodicy assumes a place in biblical scholarship in several distinctive ways. James Crenshaw recognizes that “theodicy is the attempt to defend divine justice in the face of aberrant phenomena that appear to indicate the deity’s indifference or hostility toward virtuous people.” According to Crenshaw, the defense and protection of the deity’s honor appears as the major goal of theodicy in the Hebrew Bible; this process often advances the defense of the divine honor at the expense of human suffering. Crenshaw defines theodicy even more broadly as the human search for meaning in the face of the tensions between religious claims and experienced reality.

Scholarship on biblical theodicy is devoted almost exclusively to sapiential works in which the central concern is the suffering of the individual, particularly Job and Ecclesiastes. Influenced by Greek philosophy (specifically, Platonic-Stoic thought), Walter Eichrodt sees theodicy as a central component within the conception of divine providence, which he understands to be a personal providence. Gerhard von Rad discusses theodicy in the context of the suffering of the individual and notes only in passing that theodicy is also found in some psalms of national complaint as well as in passages proclaiming divine threats of retribution presented in Deuteronomistic historiosophy.

A sociological (anthropological) approach to theodicy is presented by Klaus Koch and Brueggemann. Koch approaches the issue by analyzing retribution conceptions, arguing that in wisdom literature (and Proverbs in particular), in preexilic and postexilic prophets (especially Hosea), in Psalms, and in sagas and historical traditions, the retribution conceptions are governed by human or national actions (good or wicked ones) and their “built-in consequence.” Thus, in the national sphere, “the actions of the nation bring unavoidable consequences back on their own heads.” For Koch, theodicy is regulated in biblical literature through this sequence of action and built-in consequences. In both individual and national spheres, outcomes are determined by the human actions, which means that God is actively involved only in setting those consequences in motion. Brueggemann defines theodicy as a critique of social systems, which act or fail to act in a humane fashion, and of gods who are responsible for the social order and who sponsor these systems and ensure their continuity. Brueggemann intentionally blurs the boundaries between the social sphere and that of divine justice, since in his view the matter of divine justice cannot be addressed outside the reality of social experience. In their sociological approaches, neither Koch nor Brueggemann addresses the position of theodicy within national-communal life.

Far less attention is paid to theodicy in national-communal contexts, as a response to military defeat and destruction. In the prophetic, poetic, and historiographic writings of the Hebrew Bible, theodical explanations are associated with the two major traumas of the national experience—the destruction of the kingdom of Israel and, even more, the destruction of Judah. Yehezkel Kaufmann claims that “all of biblical historiosophy is theodical.” He points out eighth-century prophets who seek to justify God and identifies the intention of justifying God as a leading theme in Lamentations. In Paul Hanson’s opinion, the historiographic text 2 Kgs 17 preserves a theodical perspective that takes shape in the aftermath of the destruction of Samaria. Charles Whitley views Jeremiah as a pioneer in the creation of biblical theodicy, Walter Eichrodt points to Ezekiel, and Thomas Raitt designates both prophets as formulators of theodical perspectives. Robert Carroll explains the extensive concern with theodicy as arising from the pressing needs of the exiles in Babylon, a concern that leaves its mark on the literature of both the sixth and fifth centuries.

My investigations of these biblical texts focus on reactions to the national catastrophe, attentive also to contemporary, post-Shoah discussions of theodicy in the Hebrew Bible, in ancient Near Eastern texts, and in postbiblical Jewish sources. From this standpoint, the most intriguing and potentially helpful definition of the problem of theodicy is that of Ronald Green:

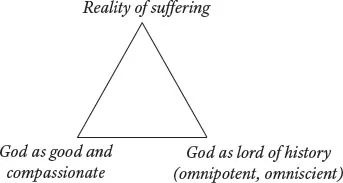

The “problem of theodicy” arises when the experienced reality of suffering is juxtaposed with two sets of beliefs traditionally associated with ethical monotheism. One is the belief that God is absolutely good and compassionate. The other is the belief that he controls all events in history, that he is both all-powerful (omnipotent) and all-knowing (omniscient). When combined … these various ideas seem contradictory. They appear to form a logical “trilemma,” in the sense that, while any two of these sets of ideas can be accepted, the addition of the third renders the whole logically inconsistent…. Theodicy may be thought of as the effort to resist the conclusion that such a logical trilemma exists. It aims to show that traditional claims about God’s power and goodness are compatible with the fact of suffering.

Fig. 1.1. Green’s trilemma of theodicy

The primary importance of Green’s definition is his recognition of “the effort to resist the conclusion that such a logical trilemma exists.” This effort is amply recorded in the biblical literature written before and after the destruction of Jerusalem. Indeed, the opposing theological positions articulated in this literature seem to illustrate the problem of theodicy as a struggle to suppress one or another of the three points of this triangle (see fig. 1.1). Green’s trilemma proves particularly helpful in describing Jeremiah’s attempt to justify God.

1.1.2. “I Myself Will Battle against You” (Jeremiah 21:1–7)

Jeremiah 21:1–7 portrays a confrontation between the prophet and two officials sent to him by Zedekiah during the final Babylonian siege against Jerusalem. They piously request divine help (21:2):

Please inquire of YHWH on our behalf, for King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon is attacking us. Perhaps YHWH will act for our sake in accordance with all His wonders, so that [Nebuchadrezzar] will withdraw from us. | דרש־נא בעדנו את־יהוה כי נבוכדראצר מלך־בבל נלחם עלינו אולי יעשה יהוה אותנו ככל־נפלאתיו ויעלה מעלינו. |

The officials use a well-known phrase drawn from the exodus tradition—עשה נפלאות (“perform wonders,” see Exod 3:20)—to implicitly express their wish for an experience of divine salvation like that of this earlier deliverance. God, they argue, has the ability to act now just as he acted long ago, to save his people even in this current crisis as they face the king of Babylon. Jeremiah’s response to the officials shows that the prophet fully understands this plea, but is determined to show them that their plea is in vain (Jer 21:3–7):

3Jeremiah answered them, “Thus shall you say to Zedekiah: 4Thus said YHWH, the God of Israel: I am going to turn around the weapons in your hands with which you are battling outside the wall against those who are besieging you—the king of Babylon and the Chaldeans—and I will take them into the midst of this city; 5and I Myself will battle against you with an outstretched hand and with mighty arm [ונלחמתי אני אתכם ביד נטויה ובזרוע חזקה], with anger and rage and great wrath. 6I will strike the inhabitants of this city, man and beast: they shall die by a terrible pestilence. 7And then—declares YHWH—I will deliver King Zedekiah of Judah and his courtiers and the people—those in this city who survive the pestilence, the sword, and the famine—into the hands of King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon, into the hands of their enemies, into the hands of those who seek their lives. He will put them to the sword; he shall not pity them; he shall have no compassion, have no mercy.

Playing upon the well-known Deuteronomic phrase that describes God’s role in the deliverance from Egypt (ביד חזקה ובזרוע נטויה), the prophet establishes God himself as Jerusalem’s primary foe: ונלחמתי אני אתכם ביד נטויה ובזרוע חזקה (“and I Myself will battle against you with outstretched hand and with mighty arm,” Jer 21:5; see Deut 26:8; also 5:15; 11:2; Ps 136:12). The change of order, pairing יד with נטויה and זרוע with חזקה, inverts the language of God’s battles against Israel’s enemies. At the same time, it echoes the formulaic refrain developed earlier by Isaiah son of Amoz to describe God’s justifiable wrath against his own people: על־כן חרה אף־יהוה בעמו ויט ידו עליו ויכהו (“that is why YHWH’s anger was roused against His people, why He stretched out His hand against it and struck it,” Isa 5:25; see 9:11, 16, 20; 10:4; 14:26). This explicit portrayal of God as the enemy is further established through verbal phrases in the first-person that illustrate God’s actions as a warrior in Jer 21:4–7:

4 I am going to turn around the weapons … and I will take them …; 5 and I Myself will battle against you…. 6 I will strike…. 7 And then … I will deliver King Zedekiah of Judah … into the hands of Kin... |