eBook - ePub

A Wild West History of Frontier Colorado: Pioneers, Gunslingers & Cattle Kings on the Eastern Plains

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Wild West History of Frontier Colorado: Pioneers, Gunslingers & Cattle Kings on the Eastern Plains

About this book

Jolie Anderson's collection of wild west tales focuses on the early frontier history of Colorado's plains and includes a look at some of the state's early pioneers like the "59ers" who promoted the state through travel guides and newspapers, exaggerating tales of gold discovery and even providing inaccurate maps to promote settlement in the plains; the perils of living and traveling the major gold routes the town of Julesburg relocated four times in a decade; feuds; Indian fights; outlaws, and even early rodeo history. These stories and events shaped the Colorado territory and are a rich glimpse into the early history of the state.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Wild West History of Frontier Colorado: Pioneers, Gunslingers & Cattle Kings on the Eastern Plains by Jolie Anderson Gallagher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Argonauts

Not every man stands over his own grave. But in 1859, Daniel Chessman Oakes pondered a rubbish-filled hole and mock headstone that bore his name: “Here lie the remains of D.C. Oakes, Who was the starter of this damned hoax!”1

Scrawled on buffalo bones in mixtures of charcoal and axle grease, the chilling epitaph greeted Oakes and his business partners along a lonely stretch of trail. The sight not only alarmed Oakes, it also confused him. An experienced prospector at age thirty-four, he had spent the previous summer scouring the South Platte River and the surrounding tributaries near present-day Denver. While at the base of the mountains, Oakes met with early prospectors in the area, men like William “Green” Russell and his party from the mines of Georgia. Russell had discovered small quantities of placer gold on Little Dry Creek in 1858. It wasn’t much, but it was no hoax either.

One member of the Russell party, Luke Tierney, had documented the finds in his personal journal and showed his notes to Oakes. Impressed with Tierney’s account, Oakes persuaded the Georgia miner to let him use the notes as the basis for a gold-seekers guide. Oakes appended his own travel advice, returned to Iowa and secured businessman Stephen Smith as a publishing partner. Smith printed History of the Gold Discoveries on the South Platte River in the winter of 1858–1859 and distributed copies to outfitting stations in Missouri River towns.

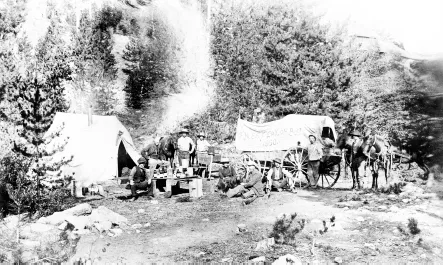

Within weeks of its publication, the Smith & Oakes guide and others like it spawned the hopes of eighty thousand people, launching one of the greatest migrations in American history. To his credit, Oakes accurately described the barren landscape and adverse conditions, but that didn’t stop would-be prospectors from embarking on a six-hundred-mile journey across dry and dangerous territory. Like the mythical Greek Argonauts seeking the Golden Fleece, desperate men crossed the plains through unknown perils, with no railroads, no stage coaches and poorly marked trails to guide them. Some rode comfortably in ox-drawn wagons, bearing optimistic slogans such as “Pikes Peak or Bust,” while others pulled handcarts or walked with packs over the bleak wilderness. All believed the journey would amply reward their efforts. They imagined riverbeds of riches waiting for them, some so hopeful that they brought empty flour sacks in anticipation of filling each one with gold. Yet when the exhausted pilgrims finally arrived at the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek, the novice gold seekers dug up nothing but rocks and sand. The furious masses turned back for home and, along the way, left effigies and graffiti to express their disgust at the gold promoters.

Below present-day Julesburg, Oakes stood over the mound the go-backers had left behind. His partners were as solemn as if they attended a real funeral. They told him, “Oakes, that crowd has buried you here. That means murder if they ever meet up with you.”2

Pikes Peakers camping in the mountains. Courtesy Denver Public Library Western History Collection, X-21803.

In an unsettled, lawless territory, Oakes found himself on a collision course with thousands of prospectors, opportunists, gamblers and outlaws. And hoax or not, Colorado’s Wild West was born.

THE CLAIM JUMPERS

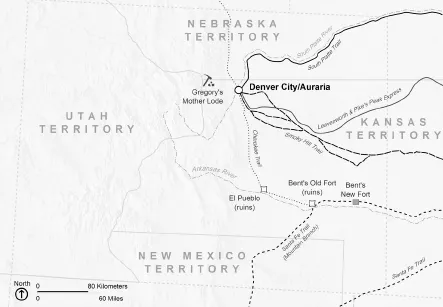

In the 1850s, Americans knew little about the far reaches of the plains. Maps of that decade referred to the terrain between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains as the “Great American Desert” or the “Pikes Peak region.” To city dwellers of the East, the western territories were vast and unexplored—as alien as the moon. But to some adventurous spirits, the uncharted country presented an opportunity to seek their fortune.

In September 1858, several groups of Kansas businessmen packed for their first trip west. The businessmen heard rumors that the Russell party found gold in the Pikes Peak region (then part of Nebraska, Utah, New Mexico and Kansas territories). But they didn’t intend to pan for gold themselves. Instead, they hoped to establish a town charter and sell tracts of land in the newly formed Arapahoe County, Kansas Territory, where Russell was prospecting. Before leaving, they met with the governor of the territory, James Denver. The governor selected county officers among the businessmen, giving them appointments such as commissioner, judge and sheriff, although the titles were meaningless. The land was established Indian territory where few white people had ventured.

The first group outfitted from Lecompton, the territorial capital. With this group of seventeen men was Edward “Ned” Wynkoop, the youngest son of a prominent Pennsylvania family. At twenty-two, Wynkoop was still an impetuous youth but also politically savvy. After befriending Governor Denver, Wynkoop received an appointment as sheriff of Arapahoe County. He later joked in his autobiography about the weightless title, writing how his duties would include keeping the buffalos and Indians in order—“a nice crowd to summon a jury from.”3

Wynkoop should not have joked about the Indians. Not long into their journey, a band of Kiowa approached his group on the Santa Fe Trail. The warriors saw that Wynkoop rode a fine horse and challenged him to a race against their best rider. Impetuously, Wynkoop accepted. On the signal, they laid into their horses for all they were worth, racing neck and neck across the prairie with Wynkoop edging just inches ahead. In the midst of the excitement, Wynkoop heard the startling crack of a gunshot and reined in his horse. He checked his rifle lying sideways in front of him on the saddle. It still smoked from the apparent contact with the pommel. With a sinking feeling, he realized his firearm had accidentally discharged during the race, its lead ball passing narrowly in front of his challenger. From behind, Wynkoop heard angry shouts and turned to see all the warriors riding hellbent in his direction. With frantic hand gestures, he tried to explain that the shot was an accident. He never touched the rifle; he never meant to harm anyone. As the warriors advanced on him, Wynkoop’s friends took up arms and prepared for a fight. He turned to his challenger and tried to explain the mishap. Fortunately, the Kiowa understood and stepped up in his defense, thus averting bloodshed.

Wynkoop later speculated on how they avoided a fight with the Plains Indians: “I know for a fact that they are not the first to precipitate a war, and whenever Indian hostilities have taken place war has been forced upon them by action of the whites.”4

Pikes Peak region in 1858–1859, showing the main trails into the territories. Map by Sean Gallagher.

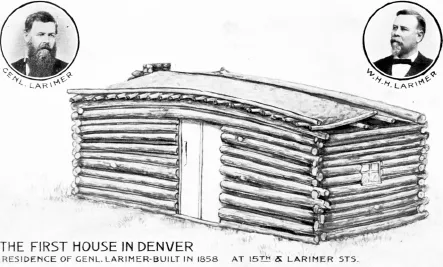

Days after the Wynkoop party departed, a second group of officials outfitted from Leavenworth. Leading this party was General William Larimer. As the eldest member at age forty-nine, Larimer felt confident that his business acumen would pay off in the Pikes Peak region. With his group was his seventeen-year-old son, William H.H. Larimer. Writing about their experiences in later years, William said that as news of gold strikes spread through Leavenworth, hundreds of eager citizens from bankers to loafers held meetings on street corners. So many planned to go west that he imagined half the population would drain away. At first, nearly eighty men asked to join their group. But as the day neared for departure, the old frontiersmen discouraged them with tales of hostile Indians, snowstorms and every imaginable danger. Of the original volunteers, only six enlisted for the journey.

One of the doubters approached the teenage Larimer as he loaded the wagons. William wrote,

The first thing we put into the bottom of our wagon was six light pine boards. We did not know just what we might want to use them for, but a fellow who was standing close by when we were loading them on the wagon remarked that they would be used for coffins…While I pretended to take no notice of his remark, I felt as if there might be some truth in it, and there was many a time afterwards when I recalled to mind his jest, and wondered if it was about to prove true.5

Ignoring the taunts and also the pleas from his mother to reconsider, the determined youth set off with his father in a group that included Charles Lawrence, Richard Whitsitt and several others. On the Santa Fe Trail, the men traveled blindly without any knowledge of the country and without meeting a single white person in either direction. As they neared Bent’s New Fort, which was the only outpost of civilization for hundreds of miles, they saw three riders coming from the west. One was Green Russell, a sorry sight after months of prospecting. His clothes were tattered and dirty, and his beard plaited into two long braids. Yet William described him as “the inspirer of all our hopes.”6 As they talked, Russell encouraged the Kansas men to push on toward Pikes Peak. Gold could be found, he assured them, and they planned to return with better equipment for extracting it.

Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site. Photo by Sean Gallagher.

General Larimer caught up with Wynkoop’s men at the abandoned ruins of the old trading post, El Pueblo (present-day Pueblo). The combined group then pushed one hundred miles north until they ascended a hill and spied a bustling settlement along the banks of Cherry Creek. As they drove their wagons around the tents, teepees and rough log shacks, they felt their business aspirations shrivel and die. Almost three hundred people had beat them to the region. Early prospectors from the Russell party had laid claim to a town site on the west bank, calling it Auraria for their hometown in Georgia. Other gold seekers had just arrived via the northern route along the South Platte River, some setting up tents and selling goods. Trappers had also settled in for the winter with their Arapaho wives and relatives.

Although late to the region, General Larimer didn’t abandon their plans for a town company. As the Kansas men unpacked their wagons and divided up the supplies, the general scrutinized the Auraria landscape. He wasn’t satisfied with its low bank along the creek, which would be prone to flooding. Abruptly, the general grabbed some provisions and told his son to yoke up the oxen and follow him to the higher, eastern bank. With a heavy sigh, the teenager repacked the wagon and drove it through the sandy creek and up the steep bank. General Larimer waited for him on the other side with a campfire blazing and four cottonwood poles crossed together, creating the first “Larimer Square.”

Even with the construction underway, General Larimer had a slight problem. Near his camp, another cabin sat on the east bank, looking abandoned in its half-finished state. Before Larimer arrived, several businessmen had already marked off 640 acres for a town they wanted to call St. Charles. The St. Charles men had asked two mountain men named William McGaa and John Smith to guard the site, while the rest traveled to Lecompton to secure a charter. But they should never have trusted McGaa and Smith. The two frontiersmen already owned shares on the Auraria side and had little interest in St. Charles. When Larimer began building his cabin, they took no notice.

Meanwhile, the St. Charles men traveled down the South Platte River and met several groups of gold seekers headed to the mountains. They worried that more people would follow. One of their leaders, Charles Nichols, decided to turn around and guard the claim himself, not realizing that he was already too late. When he arrived back at Cherry Creek, Larimer and his party had jumped the site and temporarily moved into his half-finished cabin. Nichols confronted them, arguing that the land was platted for the town of St. Charles. He stood his ground boldly but futilely until the Kansas businessmen dangled a noose in his face. Defeated, Nichols agreed to negotiate.

Cabin built by General William Larimer and his son, William H.H. Larimer, in 1858. Illustration from Reminiscences of General William Larimer and of His Son William H.H. Larimer.

As for McGaa and Smith, they willingly sided with the claim jumpers. McGaa even offered his Auraria cabin for their first meeting, where they settled the details “under the relaxing influence of a pot of hot and powerful frontier whiskey punch provided by the host.”7 With no more talk of lynching or claim jumping, their final task was to agree on a name for the east-bank town. The Kansas men finally won the argument for “Denver City,” in honor of the territorial governor James Denver. Unknown to them, Governor Denver had resigned several weeks before.

NOW MY WIFE CAN BE A LADY

Newspapers from Boston to St. Louis readily published anything they could about gold strikes in the Rocky Mountains, whether fact or fiction. William Larimer wrote, “Almost invariably the papers would add another zero to the row of digits sent by the correspondent: thus ‘$2.50 per day’ with a rocker would become ‘$25.00 per day’ when inserted in the newspaper.”8 The New York Times even heralded the Pikes Peak region as “the New California.”9 With all the exaggerated tales of riches to be found, the rush would soon become a stampede.

In Omaha, a shrewd businessman watched as waves of gold seekers rippled west. At twenty-eight, William Byers had already established himself as a successful engineer and government surveyor, but the mass migration gave him an idea for a new enterprise. Knowing that the exploding population would want a local newspaper, Byers and several partners purchased a second-hand printing press and decided to join the tide. That spring of 1859 was wet and cold, making for a miserable trip. Delayed everywhere by high water, snow and soft ground, Byers said it was discouraging to work all day at making progress with their heavy wagons, only to stop within sight of the previous night’s camp.10 Further hindering their journey, the Indians had burned off the native grasses, leaving no food for the horses and oxen.

The Indians were the least of their worries, though. Mixed in with the hoards of immigrants were thieves and gamblers—about the roughest lot of men they ever encountered. One of his partners said, “The Byers party preferred to take chances against redskin raids rather than camp with some of the white travelers they met. Some of the pioneers were of the hardboiled variety…and suspected of being not above a bit of brigandage to fatten their lean pocketbooks.”11

After weeks of rough and unnerving travel, Byers reached the base of the mount...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Argonauts

- 2. Politicians and Other Scoundrels

- 3. Rebels and Ruffians

- 4. The People of the Plains

- 5. Vigilantes and Villains

- 6. Cowboys and Indians

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author