![]()

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SACRED MOUNTAIN

![]()

Chapter 1

HISTORY AND TRADITIONS OF THE APACHE

Every morning I walk to the tent of the mountain.

I stand secure.

I am in peace.

The wind comes.

There the breath of the mountain telling me the path to take.

I am gone and am going to the mountain so that I may see the lightening break the sky in two

and rain come to heal it up again.

I come to the place where I have stepped before.

The wind blows my steps away in the dust.

The steps of all who walk here go with the wind and walk with the sky…

—Phillip B. Gottfredson, Blackhawk Productions, LLC

The Sacred Mountain

Within the Apache homeland lie four sacred mountains: Sierra Blanca, Guadalupe Mountains, Three Sisters Mountain and Oscura Mountain Peak. These four mountains represent the direction of everyday life for the residents of Mescalero. However, for the Mescaleros, one mountain is supreme, and that is Sierra Blanca, or White Mountain, and its surrounding sacred peaks. Only the tribal elders know to which peak certain attributes can be credited or which is more sacred for medicine and special power. For this book, we shall simply refer to them all as the “White Mountain.”

Grandparents would often speak of the place called White Mountain. It was there that the creator (Ussen) gave the Apaches life. It was on White Mountain that White Painted Woman gave birth to two sons. They were born during a rainstorm when thunder and lightning ripped through the heavens. When they grew to be men, the two sons, Child of the Water and Killer of Enemies, rose up and killed the monsters of the earth. Then came peace, and all human beings were saved.

That is the short version. Percy’s account is far more detailed and will fill in numerous details regarding the origin of the Apaches.

The Mescaleros are very fortunate to have a reservation in the heart of their traditional territory instead of the vast desert lands or unproductive country “given” to other bands of Apaches or Indian tribes in general. Their sacred mountain, Sierra Blanca, plays a significant role in Mescalero ceremonial and traditional practices. It is used as holy ground for ceremonies, seeking visions and collecting medicinal herbs, and it is said to be the origin of more than one mountain spirit dance group.

Sierra Blanca also provided the same bounty for the ancient Jornada Mogollon people and the desert culture inhabitants who preceded them five to ten thousand years ago.

The many moods and shadows of the Sacred Mountain entice the viewer to meet the challenge of the rugged 12,003-foot peak towering above everything else for hundreds of miles. The whispers of the ancients, the drums, the chants and the dances of the mountain spirits will also continue forever because even today, special ceremonies of the Apache prevail and are conducted annually, much as they were when the Apache were a free people.

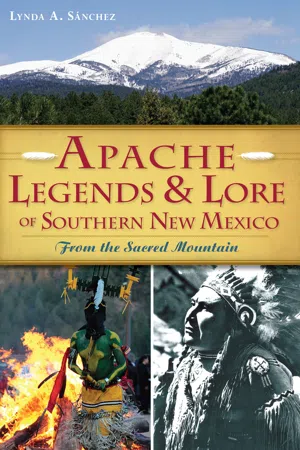

Sierra Blanca, the Sacred Mountain. Photo by Pete Lindsley.

Providing water and wildlife, the mountain was like a great fortress or refuge when the Apaches were pursued by the white man and other enemies. It was a training ground for Apache boys as they came of age. They looked to the Sacred Mountain to begin their preparations as warriors. Fasting and praying, they would sometimes have visions or their spirit animals would make an appearance and become part of the young man’s life from that point on. Many also carried a small leather medicine bag along with hoddentin (sacred pollen) and other talismans that had meaning in their lives.

Following Red-Tailed Hawk

Red-tailed hawk.

The haunting cry of a red-tailed hawk as it soars over lands dominated by the Sacred Mountain reminds us that the territory over which this magnificent hawk flies today has changed little through the centuries. True, there are more people, towns and villages appearing along the rivers and once well-traveled trails, but the lands of the Mescalero country remain much the same. The hawk’s bird’s-eye view would reveal an ancient land and a culturally rich New Mexico dependent on its natural and cultural heritage. It is an adventure in itself to follow along the trail of the red-tailed hawk, a creature some consider a “spirit animal.” In following the hawk, one learns about the Apache who considered this bountiful yet harsh land their home long before the arrival of the Spanish and Anglo pioneers. The Mescalero, Chiricahua and a few Lipan still live here and are part of the colorful mosaic of people inhabiting the region.

For centuries, populations ebbed and flowed within this territory of abundant harvests and devastating drought. Because of this “feast or famine” situation, the Apaches relied less on agricultural activities and more on hunting, raiding, trading and gathering. It worked very well for centuries until the final clash with the White Eyes.

At about the same time that the sedentary culture of the Jornada Mogollon people was disappearing, a new wave of nomads made their way into the greater Southwest, eventually becoming a significant force of conflict within the Native American community and with the newer European settlers. The Apaches had traditionally raided Pueblo villages for women and food supplies and Mexican and American settlements for horses and ammunition and other goods they could not obtain from the Pueblos. They raided deep into Mexico and as far north as Colorado.

Although there were many bands of Apaches scattered throughout the Southwest, those who dominated the lands around Sierra Blanca were the Mescalero. Named by the Spanish for their gathering of the mescal plant, they became known as Mescaleros. They were divided into two groups. A Plains-like culture raided and lived in Texas, especially in the Fort Davis, Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountain areas, while the Sierra Blancas dominated the mountain country.

The Bountiful Land

Most people driving through the area today don’t realize they are passing through an amazing, still wild and bountiful country. A southwestern pantry of edible plants and creatures used by the Native Americans of all tribes both prehistorically and into the modern era provided a well-balanced, high-fiber and delicious repertoire. Later, when the European newcomers invaded, they also learned and made use of la cocina del Apache, the Apache kitchen.

Primary vegetable products used for food by the Apaches and their neighbors were numerous. Mescal and yucca were of major importance. There are many varieties of yucca. The Spanish bayonet plant produced fruit that resembles bananas and is known as “Indian bananas.” The native peoples called this oosa and ate it either raw or roasted in hot ashes.

Datil, sotol, piñon (for nuts, firewood and incense for ceremonies), mesquite (for medicinal purpose, the rich seeds for flour and wood for fire) and dozens of roots, tubers and berries, along with pine nuts and acorns, were eaten raw, roasted or ground into flour. Mesquite beans were cooked with meat. Sometimes tasty dumplings were made of mesquite or acorn flour.

Los Mescaleros (The Mescal Gatherers)

Honey and mescal were two favorite sweets. To gather the honey from beehives, men would place a hide or canvas at the bottom of a tree or ledge. Then they would shoot arrows at the beehive until it fell onto the buckskin. Sometimes they also used smoke to create chaos in the bee colony, often hidden inside a hollow tree or cave. To gather the sweet delicacy was an exciting moment in their lives as it was so rare. Percy often described their fingers covered with the sweet miel (honey) and what a feast they had. They also left part of the honeycomb so that the bees would survive during the winter months. Bees ate the honey to survive until spring came once again to the land.

Mescal, which grew at higher elevations, was the staple food of the Mescaleros and has a sweet, smoky flavor. Apaches probably learned how to harvest the mescal or century (agave) plant from indigenous peoples to the south in Mexico. The men and boys would often help the women remove the heads (piñas, so called because of their resemblance to pineapples) or crowns of the plant (think of a large artichoke in the ground). After digging a long pit four to five feet deep, they lined it with rocks. A fire using mesquite wood produced good coals. Shoveling the glowing coals over the rock, they added layers of green, water-soaked grass. The crowns and long leaves of the mescal were put in upright with the tips being visible from the tamped earth. These would later be pulled out for testing the readiness of the mescal. The mescal heads were covered with more wet grass and canvas bags and about two feet of dirt. Sometimes steam would be visible, and the boys would immediately add more dirt to keep the heat inside the pit. It was a time-consuming process.

The mescal pits were blessed by medicine men, and after three days of cooking slowly, at long last when the dirt, stones and grass were removed and the smoky crowns were taken out of the large pits, the peoples’ hearts sang of work well done.

Piñas or cabbage-like heads of mescal would be covered with a sweet, sticky coating, and everyone looked with anticipation as the women sliced them and handed around the prize. The remainder would be placed in the sun to dry and later stored in various caches for the winter, just like the dried beef and venison jerky.

During the last part of the military campaign to destroy the Apaches, one group of soldiers was said to have destroyed hundreds—perhaps thousands—of pounds of both jerky and mescal as they swept down into just one ranchería. One can imagine what a blow that was to the Apaches after their days, maybe even weeks, of work, and it became yet another reason to hide or cache their food supplies, along with weapons, bolts of calico and other important survival items.

There are large pits found throughout the Apaches’ homeland, and once you know how to recognize them it is amazing how many have been dated back centuries. The people returned annually to their favorite harvesting areas. They also gathered the prickly pear’s fleshy pads and fruit. Once the sharp spines were removed, the prickly pear pads were eaten and often used as a poultice for wounds. Buds of the cholla cactus could be dried or used in stews and are an excellent source of calcium.

The ocotillo is high in protein, and its seeds, flowers and stalks can be used as a medicinal tea for pain and swelling or cough. Of course, the Apache had no understanding about calcium or protein content, yet the land provided a well-balanced and harmonious bounty.

Other unique plants include: Chuchupate (wild angelica root) found in the higher elevations on Sierra Blanca and used as an herbal medicine for intestinal upset, chest colds and cough and greasewood (creosote), which was very strong and pungent after a rain in the lowlands and had medical value in its leaves ground into a powder with primary use as an antiseptic. The Four Wing salt bush had several uses for both its green leaves and seeds that could be ground into flour or cooked with stew.

The tough and wide-ranging juniper tree, in addition to providing firewood, found the native folk using its berries for spicing up stews or brewing it as a tea for cough.

Fruit of the datil was nearly as important for subsistence as mescal. Like mescal, its storage properties were excellent. Although this shrub had a wide distribution depending on rain, the fruit produced was subject to moisture. The tender flowers were used as one would a fresh fruit, and the plant in general, like the yucca and sotol, was valued for other purposes. The main roots were used for soap and shampoo, the small red side roots for basket work and the leaves for twine and rope. Paintbrushes made of yucca leaves were produced especially by the Pueblos for painting of designs on ceramics. (These ceramics were sometimes traded or raided from Pueblo villages by the nomadic Apaches.) In fact, the yucca plant is often referred to as the “buffalo” of the plant...