- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Surveying the barriers that contemporary thinking has erected between the natural and the supernatural, between earth and heaven, Hans Boersma issues a wake-up call for Western Christianity. Both Catholics and evangelicals, he says, have moved too far away from a sacramental mindset, focusing more on the "here-and-now" than on the "then-and-there." Yet, as Boersma points out, the teaching of Jesus, Paul, and St. Augustine -- indeed, of most of Scripture and the church fathers -- is profoundly

otherworldly, much more concerned with heavenly participation than with earthly enjoyment.

In Heavenly Participation Boersma draws on the wisdom of great Christian minds ancient and modern -- Irenaeus, Gregory of Nyssa, C. S. Lewis, Henri de Lubac, John Milbank, and many others. He urges Catholics and evangelicals alike to retrieve a sacramental worldview, to cultivate a greater awareness of eternal mysteries, to partake eagerly of the divine life that transcends and transforms all earthly realities.

In Heavenly Participation Boersma draws on the wisdom of great Christian minds ancient and modern -- Irenaeus, Gregory of Nyssa, C. S. Lewis, Henri de Lubac, John Milbank, and many others. He urges Catholics and evangelicals alike to retrieve a sacramental worldview, to cultivate a greater awareness of eternal mysteries, to partake eagerly of the divine life that transcends and transforms all earthly realities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Heavenly Participation by Hans Boersma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Exitus: The Fraying Tapestry

The rise of modernity corresponded with the decline of an approach that regarded the created order as sacramental in character. The patristic and medieval mind recognized that the heavenly reality of the Word of God constituted an eternal mystery; the observable appearances of creation pointed to and participated in this mystery. I begin part 1 by sketching the contours of this sacramental tapestry of the fathers and the Middle Ages, a tapestry that took the form of a Platonist-Christian synthesis (chapters 1 and 2). Next, I describe the fraying of this tapestry of the Great Tradition through several late-medieval theological developments (chapters 3 and 4). The final chapter of part 1 explains that, while the Reformation reconfigured the nature-supernatural relationship, the movement was unable to restore the earlier sacramental tapestry. Today’s uncritical acceptance of postmodernity among younger evangelicals unfortunately represents a turn toward skepticism rather than an embrace of sacramental mystery.

CHAPTER 1

The Shape of the Tapestry: A Sacramental Ontology

It is difficult for Christians — whether Catholic or evangelical — to imagine a time when theology was regarded as the most important discipline.1 The modern period has taught us to look to other sources as the main guides for establishing our life together. The argument that theology is the most authoritative guide for our common (public) life seems profoundly presumptuous to many who have grown up in modern liberal democracies. In fact, many will claim that such a high view of theology strikes at the very root of our cultural arrangement. I will not dispute this claim. It seems to me unsurprising and even logical, considering that modernity takes its cue from earthly rather than heavenly realities. Its basic, dissident choice has been to take temporal goods for ultimate ends. I find myself in agreement with John Milbank’s oft-quoted statement: “The pathos of modern theology is its false humility. For theology, this must be a fatal disease…. If theology no longer seeks to position, qualify or criticize other discourses, then it is inevitable that these discourses will position theology.”2 Furthermore, if the political and economic establishment of modern liberal democracies feels threatened by the view that theology should be our primary disciplinary practice, perhaps this is simply an indication of the ultimate incompatibility between modernity and the theological convictions of the Great Tradition. None of this is to suggest that this book sets out to do battle with “outside” economic and political forces. Rather, I am taking aim at historical developments within theology, which I believe lie at the root of our contemporary cultural problems. As a result, I am calling for a resacramentalized Christian ontology (or outlook on reality).

The word “ontology” may put some people on edge. The expression places us, so it seems at least, in the area of abstract, metaphysical thought. Should Christians really concern themselves with ontology? Isn’t the danger of looking at the world through an ontological lens that we may lose sight of the particularities of the Christian faith: God’s creation of the world, the Incarnation, the Crucifixion, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, the particular ecclesial community, and Scripture itself? I understand these fears, and I appreciate the word of caution as an important one.3 Nonetheless, the objections do not make me abandon the search for an ontology that is compatible with the Christian faith. As I hope to make clear throughout this book, I believe that the Great Tradition of the church — most of the Christian era until the late Middle Ages — did have an ontology. The call for a purely “biblical” theology seems to me terribly naïve. Whether consciously or subconsciously, we all work with a particular ontology; unfortunately, usually the ontology of those who plead for the abolition of ontology turns out to be the nominalist ontology of modernity (something I will unpack in more detail in chapter 4). However, I do agree with the cautionary comment that a Christian ontology must be centered on Christ, that it dare not avoid the particularity of the visible church, and that it needs to take seriously the church’s engagement with divine revelation in Scripture.4 These concerns, I believe, were carefully safeguarded in the Platonist-Christian synthesis of the Great Tradition. This tradition was quite conscious of the fact that there is no such thing as a universally accessible, neutral “ontology” separate from the very particular convictions of the Christian faith.

Sacramental Ontology as Real Presence

Before going any further into this discussion, I think it is necessary to define some of my terms. What do I mean by “sacramental ontology,” and by the “Platonist-Christian synthesis” on which it relies? I devote this first chapter to answering this question — or, at least, to providing the basic contours of an answer. The argument of part 1 of this book is that until the late Middle Ages (say, the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries), people looked at the world as a mystery. The word “mystery” did not have quite the same connotations that it has for us today. Certainly, it did not refer to a puzzling issue whose secret one can uncover by means of clever investigation. Our understanding of “mystery novels,” for example, carries that kind of connotation. For the patristic and medieval mindset, the word “mystery” meant something slightly — but significantly — different. “Mystery” referred to realities behind the appearances that one could observe by means of the senses. That is to say, though our hands, eyes, ears, nose, and tongue are able to access reality, they cannot fully grasp this reality. They cannot comprehend it. The reason for this basic incomprehensibility of the universe was that the world was, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins famously put it, “charged with the grandeur of God.” Even the most basic created realities that we observe as human beings carry an extra dimension, as it were. The created world cannot be reduced to measurable, manageable dimensions.5

Up to this point, my explanation is probably relatively uncontroversial. Most of us, when we think about the ability of the senses to comprehend reality, realize that they are inadequate to the task. And I suspect that we generally recognize that the reason for this does not lie mainly in faulty hearing, poor vision, or worn-out taste buds, but in the fact that reality truly is mysterious. It carries a dimension that we are unable to fully express. But let me take the next step, and I suspect that in doing so, I may encounter some naysayers. Throughout the Great Tradition, when people spoke of the mysterious quality of the created order, what they meant was that this created order — along with all other temporary and provisional gifts of God — was a sacrament. This sacrament was the sign of a mystery that, though present in the created order, nonetheless far transcended human comprehension. The sacramental character of reality was the reason it so often appeared mysterious and beyond human comprehension. So, when I speak of my desire to recover a “sacramental ontology” in this book, I am speaking of an ontology (an understanding of reality) that is sacramental in character. The perhaps controversial, but nonetheless important, point that I want to make is that the mysterious character of all created reality lies in its sacramental nature. In fact, we would not go wrong by simply equating mystery and sacrament.

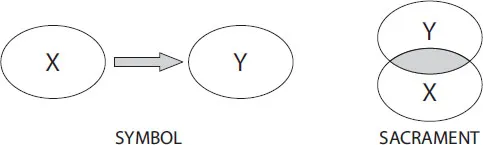

What, then, is so distinct about the sacramental ontology that characterized much of the history of the church? Perhaps the best way to explain this is to distinguish between symbols and sacraments. A road sign with the silhouette of a deer symbolizes the presence of deer in the area, and its purpose is to induce drivers to slow down. Drivers will not be so foolish as to veer away from the road sign for fear of hitting the deer that is symbolized on the road sign. The reason is obvious: the symbol of the deer and the deer in the woods are two completely separate realities. The former is a sign referring to the latter, but in no way do the two co-inhere. It is not as though the road sign carries a mysterious quality, participating somehow in the stags that roam the forests. In diagram 1, symbol X and reality Y merely have an external or nominal relationship. The distance between the two makes clear that there is no real connection between them. Things are different with sacraments. Unlike mere symbols, sacraments actually participate in the mysterious reality to which they point. Sacrament X and reality Y co-inhere: the sacrament participates in the reality to which it points.

Diagram 1. Symbols vs. Sacraments

In his essay “Transposition,” C. S. Lewis makes this same point when he distinguishes between symbolism and sacramentalism. The relationship between speech and writing, Lewis argues, “is one of symbolism. The written characters exist solely for the eye, the spoken words solely for the ear. There is complete discontinuity between them. They are not like one another, nor does the one cause the other to be.”6 By contrast, when we look at how a picture represents the visible world, we find a rather different kind of relationship. Lewis explains:

Pictures are part of the visible world themselves and represent it only by being part of it. Their visibility has the same source as its. The suns and lamps in pictures seem to shine only because real suns or lamps shine on them; that is, they seem to shine a great deal because they really shine a little in reflecting their archetypes. The sunlight in a picture is therefore not related to real sunlight simply as written words are to spoken. It is a sign, but also something more than a sign, because in it the thing signified is really in a certain mode present. If I had to name the relation I should call it not symbolical but sacramental.7

For Lewis, a sacramental relationship implies real presence. This understanding of sacramentality is part of a long lineage. According to the sacramental ontology of much of the Christian tradition, the created order was more than an external or nominal symbol. Instead, it was a sign (signum) that pointed to and participated in a greater reality (res). It seems to me that the shape of the cosmic tapestry is one in which earthly signs and heavenly realities are intimately woven together, so much so that we cannot have the former without the latter. Later on, I will need to say more about what this reality is in which our sacramental world participates. For now, it is enough to observe that the reason for the mysterious character of the world — on the understanding of the Great Tradition, at least — is that it participates in some greater reality, from which it derives its being and its value. Hence, instead of speaking of a sacramental ontology, we may also speak of a participatory ontology.

Of course, any theist position assumes a relationship between God and this world. And many evangelicals will, in addition, agree that this link between God and the world takes on a covenantal shape. God makes covenants both with the created world as a whole (Gen. 9:8-17; Jer. 33:19-26) and with human beings (Gen. 15:1-21; 17:1-27; Exod. 24:1-18; 2 Sam. 7:1-17; Jer. 31:31-33; Heb. 8:1-13). There is, I believe, a great deal of value in highlighting this covenantal relationship. But the insistence on a sacramental link between God and the world goes well beyond the mere insistence that God has created the world and by creating it has declared it to be good. It also goes beyond positing an agreed-on (covenantal) relationship between two completely separate beings. A sacramental ontology insists that not only does the created world point to God as its source and “point of reference,” but that it also subsists or participates in God. A participatory or sacramental ontology will look to passages such as Acts 17:28 (“For in him we live and move and have our being. As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are his offspring’”), and will conclude that our being participates in the being of God. Such an outlook on reality will turn to Colossians 1:17 (“He [Christ] is before all things, and in him all things hold together”), and will argue that the truth, goodness, and beauty of all created things is grounded in Christ, the eternal Logos of God.8 In other words, because creation is a sharing in the being of God, our connection with God is a participatory, or real, connection — not just an external, or nominal, connection.

Few people have expressed this distinction better than C. S. Lewis has: “We do not want merely to see beauty, though, God knows, even that is bounty enough. We want something else which can hardly be put into words — to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.”9 We do not want merely a nominal relationship; we desire a participatory relationship. In fact, a sacramental ontology maintains that the former is possible only because of the latter: a genuinely covenantal bond is possible only because the covenanting partners are not separate or fragmented individuals. The real connection that God has graciously posited between himself and the created order forms the underlying ontological basis that makes it possible for a covenant relationship to flourish.

When we talk about “real presence,” we tend to think in terms of eucharistic theology, and we ask the question: Is Christ really present in the Eucharist (the sacramentalist position), or is the celebration of the Lord’s Supper an ordinance in which we remember what Christ did by offering himself for us on the Cross (the memorialist position)? Of course, there are all kinds of shades and nuances in the various positions, but this is nonetheless a fair description of the issue at stake in the differing approaches to the Eucharist. On the one side, we have those who insist on a participatory or real connection between the elements and the heavenly body of Christ itself; on the other side, people argue for an external or nominal connection between the elements and the ascended Lord.10

Understandably, debates surrounding a participatory or real link between Christ and creation came to a head in connection with the issue of the ecclesiastical sacrament of the Eucharist. This was, after all, the central sacrament in the church’s life. Eucharistic debates, important for their own sake, had wide-ranging implications. So, for good reason, by the time the sixteenth-century Reformation came around, the church had been debating the nature of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist for centuries. Accordingly, I will devote specia...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1: Exitus: The Fraying Tapestry

- Part 2: Reditus: Reconnecting the Threads

- Epilogue: Christ-Centered Participation

- Bibliography