- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History Lover's Guide to Baltimore

About this book

Neither southern nor northern, Baltimore has charted its own course through the American experience. The spires of the nation's first cathedral rose into its sky, and the first blood of the Civil War fell on its streets. Here, enslaved Frederick Douglass toiled before fleeing to freedom and Billie Holiday learned to sing. Baltimore's clippers plied the seven seas, while its pioneering railroads opened the prairie West. The city that birthed "The Star-Spangled Banner" also gave us Babe Ruth and the bottle cap. This guide navigates nearly three hundred years of colorful history--from Johns Hopkins's earnest philanthropy to the raucous camp of John Waters and from modest row houses to the marbled mansions of the Gilded Age. Let local authors Brennen Jensen and Tom Chalkley introduce you to Mencken's "ancient and solid" city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History Lover's Guide to Baltimore by Brennen Jensen,Tom Chalkley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

BALTIMORE TOWN

SIXTY ACRES AND A DREAM BESIDE THE PATAPSCO

Although destined to become the country’s second-largest city by 1830, Baltimore was a late bloomer—a civic newbie alongside the likes of Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston, all of which date to the 1600s. And Baltimore didn’t arise organically from a location naturally fortuitous for trade but rather was created by lawmakers in 1729 as a real estate speculation.

Colonial-era Maryland at the time was an agrarian backwater with economic activity centered largely on self-sufficient tidewater plantations. Its sleepy capital Annapolis (founded in 1649 and called Providence in its earliest days) was but an overgrown village and served as the principal urban center for an agrarian colony with little natural need for townships. To shake up this moribundity and spur development and trade, the Maryland Assembly set about birthing towns by legislative writ as far back as 1683. Many of these would-be communities never made the jump from paper charter to proper towns, but Baltimore is one that did—eventually. An act passed in 1729 acquiring sixty acres on the north shore of the Patapsco River from brothers Charles and Daniel Carroll. It was then carved up into sixty lots; streets and lanes were laid out, and the roughly acre-sized parcels were offered up for sale with the stipulation that purchasers must erect buildings on them within eighteen months.

They called it Baltimore Town. The name comes from the Calverts, a clan of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English nobles whose Irish peerage made them the “Barons of Baltimore,” an Anglicization of the Irish-Gaelic name of their estate, Baile an Thí Mhóir e, meaning “Town of the Big House.” Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, was the first proprietor of the Province of Maryland, a position he held from 1632 to 1675. (His first-lord father, George Calvert, is the one who had applied to King Charles I for a charter to the lands, but he died a few weeks before it was granted; neither Calvert ever set foot in what would become Maryland.)

Artistic depiction of Baltimore viewed from Federal Hill, circa 1830. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Sales were slow, and only seventeen lots were purchased after nearly two years—several had already been defaulted on. You could argue that it wasn’t the wisest location—the acreage was hemmed in by steep slopes to the north and marshland to the east. And there was competition. In 1732, Jones Town was chartered on ten acres east of Baltimore Town on the other side of a sizable stream known as the Jones Falls (after David Jones, who had settled nearby in 1661). A clutch of buildings already existed there, which is why Jones Town is also known as Old Town. Meanwhile, ship’s carpenter William Fell, whose brother Edward was living in Jones Town, began settling a peninsula just southeast of Baltimore Town where he’d set up shop in 1726. He named it Fell’s Prospect, and the deeper waters off its shores facilitated shipping and shipbuilding. (William Fell’s son Edward would formally lay out the town of Fell’s Point in 1763.) By the 1740s, Baltimore Town was but a clutch of houses huddling around muddy streets behind a wooden stockade of the sort associated now with the Wild West—erected here, reports suggest, to protect the fledgling town from marauding pigs, not Native Americans. (In any event, shivering Baltimoreans eventually pulled it down one winter for firewood.)

While tobacco was the state’s principal cash crop (and enslaved labor the crop’s principal workforce), Baltimore Town never became a major port for this commodity. Instead, wheat became the town’s first successful export after Scotch-Irish trader Dr. John Stevenson successfully sent a shipload to Ireland in 1750. Grain farming wasn’t dependent on enslaved hands and wasn’t as hard on the soil as tobacco, and it facilitated development away from the tidewater areas. Milling the grain before shipment was a logical next step, and soon Baltimore and environs were finding a mercantile footing. Marshes were drained and bridges built to connect the trio of settlements. Roads, crude as they were, fanned out from the upstart outpost on the Patapsco.

The city added new acreage—some virginal and some already developed. Fell’s Point, which had grown into a bustling port and center of the maritime trades, was incorporated into Baltimore Town in 1773. (Baltimore had absorbed Jones Town back in 1745.) Its shipyards developed fast and maneuverable crafts that would come to be called Baltimore clippers. By the Revolutionary War, Baltimore had nearly seven thousand inhabitants, although its streets were still unpaved rivers of mud—something the delegates in the Continental Congress complained about when the threat of British attack drove them here from Philadelphia in 1776. For two wintery months, the de facto nation’s capital was a three-story Baltimore tavern and inn known as the Henry Fite House. Here, delegates granted George Washington “extraordinary powers” to wage war. Later dubbed Old Congress Hall, it was home to financier and philanthropist George Peabody for a time and burned down in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904. (The Baltimore Civic Center erected over the site in 1962 witnessed its own British invasion: a Beatles concert in 1964.)

With Baltimore unscathed by actual fighting and with its nimble ships making mincemeat of the Brits’ would-be naval blockade, the war boosted the city’s fortunes and set it up for peacetime prosperity. Yes, the streets finally got paved in 1782—streetlights were added two years later. A boomtown atmosphere prevailed. “I heartily enjoy the flourishing situation in which I find the town of Baltimore,” remarked the Marquis de Lafayette, the French aristocrat and victorious general of the Continental Army when feted here in 1784. George Washington called Baltimore “the risingest town in America” in 1798. One is hesitant to correct the Father of Our Country, but that’s not quite right. One year earlier in 1797, the Maryland General Assembly finalized an act upgrading Baltimore Town to Baltimore City, giving its citizens greater political autonomy.

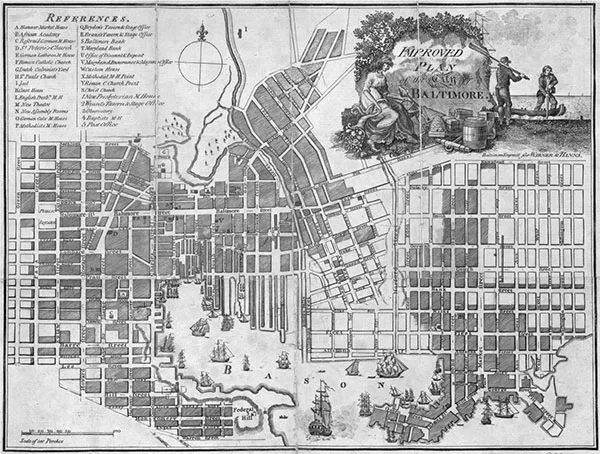

An 1804 map of Baltimore. Fell’s Point and its distinctive “hook” jut into the harbor in the lower right. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The growth only continued. During the first decade of the nineteenth century, the city’s population increased 75 percent to more than forty-six thousand—moving in on Philadelphia as the nation’s second city. In 1806, ground was broken on the nation’s first cathedral, today’s Basilica of the Assumption. Along with shipping and shipbuilding, industrial activities included textiles, sawmills, ironworks and brickyards. White-collar trades developed as well. Irish-born linen merchant Alexander Brown arrived in 1800 and soon established Alex, Brown & Sons, the nation’s first investment bank. (Two centuries and innumerable mergers and acquisitions later, a financial entity by that name continues to flourish.)

But soon enough, war drums sounded anew. And Baltimore would not be able to avoid being bloodied this time.

YOUR GUIDE TO HISTORY

Carroll Mansion

800 East Lombard Street • Inner Harbor

(410) 605-2964 • www.carrollmuseums.org • Admission Fee

Maryland-born Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence, lived in this circa 1808 house for a dozen years and was the last and longest-lived signer when he died here in 1832 at age ninety-five. Well, he wintered here with his daughter and son-in-law (who actually owned the place) and spent the fair-weather months on his sprawling plantation, Doughoregan Manor, near Ellicott City, Maryland, where hundreds of enslaved workers toiled. (It is owned by the Carroll family to this day and never open to the public.)

There’s not much to see within this stout, dormered Federal house, as period furnishings are few. As you’re guided along the creaky floors, the most fascinating things are the tales of what the building’s been through in its two hundred–plus years. A tony address in Carroll’s day (when it was looked after by enslaved domestics residing in the attic), the environs later took a socioeconomic nosedive; at various times, the house served as a distillery, saloon, immigrant tenement, sweat shop and vocational school. Up until 1954, it was a recreation center with basketball hoops hung on walls of the high-ceilinged parlor where Carroll had once entertained Alexis de Tocqueville and the Marquis de Lafayette. It’s also a joint attraction with the Phoenix Shot Tower, a short walk away (discussed in Chapter 8), where Carroll laid the cornerstone in 1828.

Federal Hill

Neighborhood adjacent to Federal Hill Park • South

https://fedhill.org

Two blocks west of Federal Hill Park, the 100 block of East Montgomery Street is paved with stones and lined with houses dating to the early nineteenth century and one, at least (the wooden house at 130 East Montgomery), from the end of the eighteenth. The towering outlier at 125 East Montgomery began as a volunteer firehouse in 1854. This and a number of the surrounding blocks are showcases for the careful and costly restoration of private homes in a neighborhood subject to both federal and local historic preservation rules. The stone pavement (restricted to that one block of Montgomery Street) is made not of cobblestones but rather of so-called Belgian blocks, rough brick-sized chunks of granite that arrived in Baltimore as ballast in wooden sailing ships. They have been worn smooth by two centuries of traffic. One noteworthy home here is the self-proclaimed, aptly numbered “Little House” at 200½ East Montgomery Street, not quite nine feet wide. The entire neighborhood extending to the east and south of the park is now popularly known as Federal Hill. The neighborhood commercial area, lining Light Street, is anchored by the venerable but much-updated Cross Street Market.

The American Visionary Art Museum turns a Federal Hill slope into an impromptu movie theater. Explorer John Smith made note of this prominent hill in 1608. Courtesy of AVAM/Nick Prevas.

Federal Hill Park

300 Warren Avenue • Inner Harbor

This roughly ten-acre grassy promontory on the south side of the Inner Harbor is one of the city’s most distinctive natural features. English explorer John Smith made note of a large clay hill back in 1608. It picked up its name in 1788 after it was the setting for a huge, boozy gathering to celebrate Maryland’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Green and groomed today, for much of its life the hill had a battered and cliff-like look. Over the years, it was mined for clay and other minerals and even tunneled into for underground beer storage. Beginning in 1785, ship spotters in an observation tower used a system of flags to give downtown merchants advance notice on what vessels were tooling up the harbor. It was made a park in 1880, and benches beneath shade trees provide unparalleled city views (and a chance to catch your breath if you scramble up the steep banks). The park includes a Civil War–era cannon (pointing down on the city, as it would have when the Union forces occupied the hill in 1861), a statue of Major General Samuel Smith and a monument to Major George Armistead, leaders of the Battle of Baltimore in 1814 (with Smith in charge of land defenses and Armistead commander of Fort McHenry).

Davidge Hall

522 West Lombard Street • Downtown

(410) 706-7454 • https://medicalalumni.org/davidge-hall • Free

Erected in 1812, the domed, Neoclassical Davidge Hall is North America’s oldest medical education building in continuous use. It was the inceptive building of the College of Medicine of Maryland (now the University of Maryland School of Medicine) and a possible inspiration for Thomas Jefferson’s famed Rotunda at the University of Virginia. The handsome brick structure, designed by Robert Cary Long Sr., Maryland’s first native-born architect, sports a portico with eight Doric columns. But some of its more curious architectural features are less obvious, having been designed in darker days and with sinister events in mind: cadaver riots.

Human dissection was an increasingly important component of medical education early in the nineteenth century, although it was viewed as distasteful—even sacrilegious—by some of the public. It didn’t help that grave robbing was a major source for medical school cadavers at the time. The building’s namesake, Dr. John Beale Davidge, who would become the medical school’s first dean, erected a private anatomy theater in 1807, only to see it destroyed by an angry mob in its first week. Five years later, Davidge Hall was laid out with potential riots in mind: first-floor windows are few, the main door is stout and a designated dissection area is tucked away on an upper floor served by a back stair that teachers and students could retreat down should anti-dissection mobs storm the front.

The University of Maryland Medical School’s Davidge Hall features a domed room where medical students have been taught since 1812. Courtesy of Brennen Jensen.

The building’s main features include the first floor’s bi-level and semicircular Chemistry Hall, which accommodates about two hundred. Above this sits the building’s show-stopper: Anatomical Hall, an amphitheater tucked under the ornate dome and skylights. A brass plaque in the floor marks where French Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette stood to receive an honorary degree in 1824. A mini-museum of sorts rambles through the perimeter, with mummified body parts once used for training along with a complete desiccated cadaver named Hermie. A barrel of the type once used for shipping cadavers is also displayed (the bodies were submerged in whiskey as a preservative and deodorant). Additional artifacts and stories relate to prominent alumni, such as Dr. Samuel Mudd, who went to prison for treating Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth’s broken leg.

Ultimately, no cadaver riots occurred at Davidge Hall, although the edifice was involved in the country’s only known case of “burking”—murder committed in order to sell the victim’s body. (We owe the word to one William Burke, a Scotsman who killed more t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Baltimore Town

- 2. Fell’s Point and the Waterfront

- 3. The Rocket’s Red Glare

- 4. A Higher Calling

- 5. Smokestacks and Locomotives

- 6. The African American Experience

- 7. The Legacy of Wealth

- 8. Brick, Mortar, Marble and Steel

- 9. Arts and Letters

- 10. Of Stage and Screen

- 11. Sporting Life

- 12. The Green Escape

- Bibliography

- About the Authors