- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

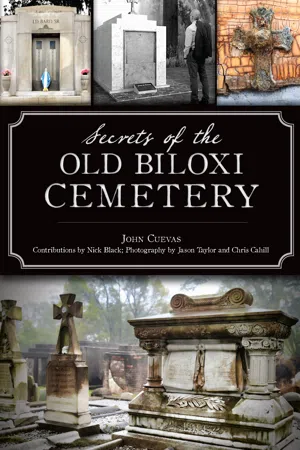

Secrets of the Old Biloxi Cemetery

About this book

The countryside between Mobile and New Orleans teems with memorials, but few historic spots occasion pause for reflection like the Old Biloxi Cemetery. Burials go back to the eighteenth-century French settlement, when Biloxi was the planned capital of the Louisiana territory. Secrets abound in the old cemetery--not exactly buried, since many prominent inhabitants sealed unsolved mysteries with their final remains in the aboveground tombs developed here. Author John Cuevas explores the fascinating history of the cemetery, including the massive restoration of the iconic resting place of his ancestor Juan de Cuevas, great-grandfather to more than nine thousand Gulf Coast families.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Secrets of the Old Biloxi Cemetery by John Cuevas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

CEMETERIES IN AMERICA

Humans have both feared and worshipped death since the beginning of time. Rituals and religious practices have been developed in an attempt to explain and understand the mystery surrounding it. Most cultures today use cemeteries to memorialize the dead, not only out of respect for those who have passed on, but also as a therapeutic way for the living to deal with their grief and find closure. Monuments and memorials to the deceased give family and friends a place to visit and feel connected to the person they lost.

Cemeteries as we know them today are a relatively new idea. Our modern cemeteries, known as “garden cemeteries,” developed out of necessity. As populations increased over time, European countries ran into problems with disposing of their dead. Originally, everyone wanted to be buried in their churchyards to be closer to God. Recognizing an opportunity to increase their coffers, churches began selling expensive plots inside the churches themselves, giving people the feeling of being even closer to the Almighty. It wasn’t long, however, before churches and the churchyards were overflowing.4

Aside from those in the churchyard, some cemeteries are small family plots, isolated in the country, and still others are sanctioned areas at the edges of cities or towns. No matter the type, all cemeteries have one thing in common: they are filled with headstones, markers and mausoleums to help us remember our loved ones and tell future generations about the people who were buried there.

Wandering through the Old Biloxi Cemetery, one can feel the weight of history chiseled in the weathered stones. The old markers reveal secrets about the deceased and the times in which they lived. The practice of marking a grave goes back to the ancient Egyptians. In the Roman catacombs, early Christians were buried in slots along the walls of the subterranean tunnels. These niches were then sealed with a slab inscribed with the person’s name, date of death and, usually, a religious symbol, such as a fish, which was the mark of early Christians. During the Victorian era (1837–1901), grave markers became very elaborate, fashioned after those of the ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians. After World War I, however, grave markers became simpler and less ornate. Plain wooden crosses or simple stone slabs carved with the deceased’s name and an epitaph became the norm.

Other cultures practiced cremation, but the Christians didn’t believe in cremation. They believed that the body should be kept intact, in readiness for the final resurrection. Burial in the church or the churchyard was the only way to dispose of the dead. In America, the churchyard remained the most common burial place through the end of the 1800s. Unfortunately, the stench and the spread of diseases made churchyard burials a problem. To address the crisis, cities began to buy large blocks of land outside the city limits where they could bury the bodies. The term cemetery is Greek for “sleeping place,” and indeed, cemeteries can be thought of as sleeping places for those who have passed away.

While city cemeteries are the norm today, private family cemeteries were originally more common. In early America, people would stake out a plot of land somewhere on their property to begin a family burial site—usually in a wooded area on the edge of their farm. It was not uncommon to allow other families to bury their loved ones in the same plot. Some of these plots became real cemeteries as more families were buried on their neighbors’ properties. The Krohn Cemetery at 16299 Krohn Road in Vancleave, the Moran Cemetery at 10059 Santa Cruz Avenue in D’Iberville and the Quave Cemetery at 3315 West Race Track Road also in D’Iberville are just three examples of these small family cemeteries that have survived. There are many more family burial sites like these along the Gulf Coast. In many cases, the early markers were wooden crosses. In a very short time, these crosses rotted away, often leaving the graves unmarked and forgotten.

The movement toward garden-like cemeteries spread to America after the creation of the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France. The cemetery opened in 1804; it was the first garden-style cemetery and is the largest municipal cemetery in Paris.5 The neoclassical architect Alexandre-Theodore Brongniart (February 1739–June 6, 1813) designed the cemetery. He used English gardens as his inspiration, with uneven paths and diverse trees and plants. He lined the way with carved graves. His plan was to include various funerary monuments, but in the beginning, only one was ever built. It was the tomb of Count Jean-Henry-Louis Greffulhe (May 21, 1774–February 23, 1820), a French banker and politician. Père Lachaise has become the most visited cemetery in the world, with over 3.5 million visitors a year.6 After Père Lachaise, people began to appreciate the peaceful setting that the garden-style atmosphere provided for families who wanted to remember their loved ones.

The first garden-style cemetery in America was the Mount Auburn Cemetery, created in 1831 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Designed by Dr. Jacob Bigelow (February 27, 1787–January 10, 1879) and Henry A.S. Dearborn (March 3, 1783–July 29, 1851), it featured an Egyptian-style gate and fence, a Norman tower and a granite chapel.7 It was an immediate success, inspiring similar cemeteries in cities throughout the United States. These garden-style cemeteries were the exact opposite of crowded churchyards, where a person’s status in society dictated the location of their grave.

New “garden cemeteries” became popular not only as burial grounds but also as public recreation areas. They developed into beautiful, peaceful areas where the dead could rest far away from the hustle and bustle of the cities. These places were beautifully landscaped areas where people could relax and stroll around the grounds and even picnic. These cemeteries became the forerunners of our modern parks.8

The Victorians can be credited with making cemeteries what they are today. They created a park-like atmosphere where family outings and picnics were held. The people of that era were more comfortable with the subject of death than we are today, since dying was a part of most of their lives. Because of such devastating diseases as yellow fever and cholera, few people lived past forty. So, to be close to their deceased relatives, families would gather in the cemeteries to talk and visit with the living and the dead. A man in 1884 commented on why his family chose to eat in the cemetery: “We are going to keep Thanksgivin’ with our father as [though he] was as live and hearty this day [as] last year.”9

As cemeteries became popular hangouts, it became important to show plots off to friends. This effort to “keep up with the Joneses” resulted in the creation of overstated mausoleums and ornate tombstones. This trend toward architectural gingerbread and flashy structural elements reflected the gaudiness of the Victorian era. This was the most extravagant architectural period in the United States, in which some of the most lavish and beautiful vaults were created.

Like all fads, dining in cemeteries began to diminish by the early twentieth century. Advancements in medicine reduced the number of early deaths, while the proliferation of parks throughout the country offered a more inviting place for relaxation and picnics. Today, there are only a few cemeteries with enough available land for large gatherings, and most current city policies will no longer allow for picnics.

Over the past several years, visiting cemeteries has become a hobby for a large number of people. This activity is so widespread that the people who participate have their own name. They have become known as “gravers.”10 The idea of visiting cemeteries as a form of entertainment may, at first, seem somewhat twisted, but for those who are seeking information, it is more than something ghoulish. It is an informal classroom that not only entertains but educates. The gravers’ interests can include a wide variety of topics. Some are genealogists who visit various cemeteries to take notes and fill in the missing branches of family trees. Others plan their trips around the burial places of public figures or entertainers. Patriotic gravers might visit the resting places of the soldiers who died in the Civil War, World War II or some other military conflict. Gravers who are preservationist actually visit cemeteries with bleach in hand to scrub and clean the aging stones. In general, gravers consider it fun to visit cemeteries. Some have no other agenda than to just stroll among the tombstones or just hang out.

Hardcore gravers have created a culture around their interests in documenting the dead. They collect cemetery jokes and stories from the tombstones, in addition to offering advice on a graver’s needed supplies, such as the proper kneepads, high-resolution digital camera, tracing paper for rubbings and shaving cream to wipe across worn inscriptions to make the words more legible. The more serious gravers create individual records for each of the deceased by transcribing the information directly from the headstone. They dismiss the use of obituaries to gather information, emphasizing, instead, the importance of seeing the actual tombstones. This means that a trip to the cemetery cannot be avoided. Those researchers who carelessly collect information in the comfort of their living rooms from newspapers instead of tombstones are called “ploppers.” They believe that ploppers most often enter erroneous information about names, dates or burial locations. Serious gravers accuse them of being more interested in the number of records they collect rather than the quality of their work.

Over the years, certain customs have developed around cemeteries and burial sites in Louisiana and in the old communities along the Gulf Coast. One of the most popular traditions has been the celebration of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. These are the results of the strong Roman Catholic influences throughout the area. All Saints’ Day honors the saints. There are evening masses celebrated in cemeteries and a blessing of the graves by the attending priest. All Souls’ Day celebrates families and friends who have passed away. It is a festive time when communities come together to visit with friends, clean and decorate the graves with flowers and pay respect to the deceased.11

The above-ground tombs are a tradition brought to the area by the Spanish. As Lucy L. McCann of the Louisiana State Board stated, “Placing burial vaults above ground or partially above ground is an aesthetic or cultural preference that has nothing to do with the law or the water table.” The first cemetery in New Orleans was St. Peter, which was an in-ground cemetery near the French Quarter. When it was filled, St. Louis I was created. It was an above-ground burial site designed after the old cemeteries in Spain. The use of vaults was a practical matter, as they allowed for more than one burial in the same spot.

Another popular custom was to bury the deceased with their head facing west and feet facing east. According to Christian and Jewish tradition, the Messiah will return to this world from the east, and the person would want their body to rise from the grave facing the Messiah.

One custom was the “year and a day” rule.” It was tradition not to open a tomb until at least one year and a day had passed since the last burial. This was a practical step that allowed enough time for the previous body to completely decompose before another one was placed in the same tomb. The extreme heat and humidity that builds up in these tombs accelerates the decomposition process. This custom has been followed for generations. But recently, the rule has been changed to two years and a day as an extra precautionary measure.

These customs were also practiced in the Old Biloxi Cemetery. Several of the tombs have been used for multiple burials, and all of the deceased in the original section were buried with their feet toward the east.

To some, cemeteries are mysterious places, full of superstitions and sorrow. But cemeteries should not be thought of as spooky places or even as places of sadness and loss; rather, they should actually be appreciated as windows to the past.

2

THE OLD BILOXI CEMETERY

The Old Biloxi Cemetery is located at 1166 Irish Hill Drive on a high bluff overlooking the gulf, only a stone’s throw away from the hectic traffic of Highway 90. The serenity of this historic site is a welcome contrast to the glitz and glitter of the twenty-four-hour casinos just minutes away. A visit to the cemetery is a pleasant way to spend an hour or an entire day, listening the gulf breeze rustling through the trees while getting to know some of the men and women who laid the foundation for today’s Mississippi Gulf Coast.

The Old Biloxi Cemetery officially opened on November 27, 1844, when the family of Louis Lalanzette Fayard donated approximately six acres of his land to the city for use as a graveyard.12 The cemetery was part of a much larger parcel that had been granted to Fayard by the U.S. government on April 25, 1812, and was already being used for burials when it was deeded to the city.13

No records have been found to say when the first burials took place on the site, but some historians believe the area was probably used for burial as far back as the early 1700s, when Biloxi was the planned capital of the Louisiana Territory. The site of the Old Biloxi Cemetery is on land near the proposed Fort Louis, where small, scattered groups of people had been living since the French first arrived. Some most likely would have been buried near their homes, while others might have chosen the land near the old Biloxi Cemetery because of the site’s protective elevation. This offered some security from storm surges, and its proximity to the newly intended Fort Louis made it an ideal spot for the early French settlers to dispose of their dead.14

From the very beginning, the French had to endure horrible living conditions. Hundreds and probably thousands died between 1719 and 1721 from disease, a lack of food and the raw conditions of the undeveloped territory. Many died as a disastrous result of John Law (1671–1729) and his Mississippi Company, while others died from the yellow fever epidemic of 1853. John Law imported hundreds of people from Germany and other European countries who had been deceived into believing they were headed for paradise.

The French had arrived on the coast on April 9, 1682. When French explorer René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle (1643–1687) became the first to reach the mouth of the Mississippi River, he claimed the entire basin for France, quickly planting a cross as a physical marker of French possession, naming the new territory La Louisiane in honor of King Louis XIV (1638–1715).15

La Salle believed that the only way to retain control of this vast region would be to colonize the area. After convincing the king this was the right thing to do, he started the first settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Louis XIV commissioned Pierre Le Moyne Sieur d’Iberville (1661–1706), a thirty-seven-year-old from Quebec, to return to the mouth of the Mississippi River and set up a new settlement.

D’Iberville, along with his nineteen-year-old brother, Jean Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (1680–1767), a group of about two hundred colonists, two armed ships and two smaller vessels, departed from LaRochelle, France. On their initial arrival in the gulf, the French explorers searched the shallow waters along the coast for a harbor that was deep enough to accommodate their large ships. On February 10, 1699, they discovered the Ship Island Harbor.16

After a camp was set up on Ship Island, the crew determined that the mouth of the Mississippi River was not an ideal place to build a fort. They finally decided that Biloxi was the best site and returned on March 30, 1699, to begin construction. The fort was named after the French minister of the navy Jean-Fréderic Phélypeaux, comte de Maurepas (1701–1781).17

The first summer at Fort Maurepas in Biloxi (known today as Ocean Springs) was almost unbearable, as the young colony was forced to endure the extreme heat and draught of 1700. The people suffered, as the food crops dried up from the sizzling heat and lack of rain. The insects were particularly bad that year, and the men were attacked by swarms of mosquitoes, horse flies and other biting insects. Boredom, complicated by dysentery and fever, caused the men’s morale to tank. The threat of alligators and snakes was a constant concern, while the shrinking of the food supply was hastened by an increasing number of Canadians continuing to a...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- HalfTitle

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Cemeteries in America

- 2. The Old Biloxi Cemetery

- 3. Noteworthy Burials in the Old Biloxi Cemetery

- 4. The Tomb Boom, by Nick Black

- 5. Secrets of the Cuevas Tomb

- 6. The Mystery Woman

- 7. Preservation of the Old Biloxi Cemetery, by Nick Black

- 8. The Rededication Ceremony

- Appendix: The Cuevas Family of Cat Island.

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author