![]()

PART I

BEGINNINGS

Almost as soon as there were European settlers in North America, there were also several varieties of Christianity. Despite popular impressions, the English Puritans did not arrive first. Even in the territory that would become the United States, the Puritans were preceded by their near, but not very dear, fellow Englishmen, the state-church Anglicans. Representatives of Holland’s Reformed Church were also fairly well established in New Amsterdam (later New York) before the main body of Puritans first glimpsed Boston in 1630. Soon German-speaking believers of many types joined English Quakers in William Penn’s Pennsylvania, Swedish Lutherans were in Delaware, and Presbyterians from Scotland and the north of Ireland had established a foothold on Long Island, in New Jersey, and in Pennsylvania.

Yet even before any British Protestants had appeared on the scene, a substantial Catholic presence had already taken root in the New World. From Spain, Catholic priests had come to convert the Native Americans of the great Southwest. In what is now Canada and along the Mississippi River, Catholic missionaries from France were pursuing their work among Indians before missions by English Protestants had even made a start.

The early pluralism was also cultural. Before there were English Puritans in Massachusetts and almost as soon as there were Catholic missionaries in the Southwest, black-skinned immigrants from Africa had arrived in Virginia. Although the twenty Africans off-loaded in Virginia by a Dutch trader in 1619 were not slaves in a strict sense, slavery had already become an essential building block of European expansion in the New World. From the first Portuguese explorations in West Africa to the later and more numerous colonies planted in the Western Hemisphere by the Spanish, the French, the Dutch, and the English, human bondage was a central reality—socially, politically, and economically. It was also a religious reality. Africans, who soon replaced Native Americans as the primary slave population, retained aspects of African indigenous religions. Some from Muslim regions brought remnants of Islam to the New World. Yet at first in small bits and pieces, but then in a more systematic fashion (and often in surprising ways), many of the slaves in North America began to accept Christianity, the religion of the Europeans. From the start, Euro-American Christians, even as they proclaimed the freedom of the gospel, held slaves or benefited from the slave trade. The interplay between colonization, slavery, and faith existed from the first.

Diversity and cultural conflict were, thus, the rule from the beginning of Christianity in North America. The diversity and the conflict had not begun in the Western Hemisphere but grew naturally from the European circumstances that prevailed at the time of the first efforts to colonize the Western Hemisphere. When Columbus sailed in 1492, he was simply a loyal son of the church. When the gleam of New World evangelization first shone in the eyes of European Christians, there was only one recognized form of European Christianity. But within two generations the Protestant Reformation and a countervailing surge of reform within the Roman Catholic Church left Europe religiously divided. These divisions, in turn, set the stage for the Christian pluralism of North America.

In more recent centuries, American ties to majority world Christians have grown stronger as missionaries from Canada and the United States have circled the globe and as Christian immigrants from many regions have come to North America. For the first centuries of Christian settlement, however, North America was a “receiving,” not a “sending,” region. It was a place where Christian heroism, Christian exploitation, and the quiet realities of day-to-day Christian life were set on their course by the experiences, the assumptions, and the values of the European churches.

![]()

1. European Expansion and Catholic Settlement

Within a lodge of broken bark

The tender Babe was found,

A ragged robe of rabbit skin

Enwrapp’d His beauty round;

But as the hunter braves drew nigh,

The angel song rang loud and high—

Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born,

In excelsis gloria.

*****

O children of the forest free,

O sons of Manitou,

The Holy Child of earth and Heav’n

Is born today for you.

Come kneel before the radiant Boy,

Who brings you beauty, peace and joy—

Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born,

In excelsis gloria.

This carol, written in the language of the Huron Indians, is said to have been composed by Jean Brébeuf, pioneer Jesuit missionary, in 1642.

The European discovery of America began in the late fifteenth century, only a generation before the start of the Protestant Reformation. The European exploration of America was intensified during the second half of the sixteenth century, in the same era as the reform of the Roman Catholic Church sometimes called the Counter-Reformation. And the European settlement of America took place largely in the seventeenth century, when the divisions and subdivisions of the European Reformation assumed institutional and intellectual permanence. For better and for worse, these events in the Old World dictated the shape of Christianity’s early history in the New.

The world, as viewed by Europeans, as they began to cross the Atlantic. Library of Congress

The age of Reformation was a time of social, intellectual, national, and economic expansion as well as religious change. Western Europe entered the sixteenth century stronger and more aggressive than it had been at any time in its history. French political power was growing steadily, and its citizens’ achievements in finance, art, and literature were often spectacular. After 1485, the English throne was occupied by the energetic Tudors. Especially under Henry VII (ruled 1485–1509), Henry VIII (1509–1547), and Elizabeth I (1558–1603), monarchs as filled with love for their country as they were with ambition for themselves, England emerged as a major European power. In Spain during the last years of the fifteenth century, the kingdom was united under Ferdinand and Isabella, the last strongholds of the Muslim Moors were overcome, and the nation took the lead in exploring the New World. One result of growing strength among these great nations, and also lesser ones such as Portugal and Holland, was competition in Europe. Another was competition for empire overseas.

The European nations wanted profit from their American explorations, but only Spain found it, and only for a brief period. Yet the drive for raw materials from the colonies, and then a more general pursuit of trade, became a permanent feature of European life. It was this drive that inserted the trade in human beings so deeply into the cultures of North and South America. The spirit of the Renaissance also stimulated exploration across the Atlantic, for the virgin territory of America held out the promise of new knowledge, personal glory, and liberation from stifling European traditions. Expansion to America, in other words, shared fully in the energies that drove Europe as a whole during the early modern period.

Also from the start, however, European believers took a religious interest in America. As the career of Christopher Columbus illustrates, it was an interest with both the fidelity and the tragedy that would characterize the whole history of Christianity in North America. Columbus’s very first entry in the diary that recorded his journey to America in 1492 expressed the hope that he could make contact with the native peoples in order to find out “the manner in which may be undertaken their conversion to our Holy Faith.” On his second journey in 1493 Columbus took with him Catholic friars whom he hoped could convert the Indians he had seen on the first voyage. To the Spanish monarchs, Columbus insisted that profits from his voyages be used to restore Christian control over Jerusalem. He also entertained a very high sense of his own divine calling. In a lengthy manuscript penned after his third voyage, A Book of Prophecies, Columbus recorded the many passages from Scripture that he felt related to his mission to the East Indies: “neither reason nor mathematics,” he wrote in this manuscript, “nor world maps were profitable to me; rather the prophecy of Isaiah was completely fulfilled” (i.e., Isa. 46:11—“the man that executeth my counsel from a far country”).

The other side of the picture, however, concerns Columbus’s conception of himself and the effects of his activities on the inhabitants of the New World. Columbus’s zealous belief in his own messianic mission seems partly the result of delusions of grandeur. Moreover, the way Columbus’s subordinates treated Native Americans was often anything but Christian. The forty sailors he left behind on the Island of Hispaniola to construct a fortress in 1492 so wantonly raped and pillaged that the Indians rose up and slaughtered them. For such resistance, however, the Europeans exacted a gruesome total revenge: in 1492 Hispaniola had an Indian population in the millions, but within sixty years that population was virtually wiped out by diseases contracted from the Europeans.

Modern reactions to Columbus’s “Christian mission” are, not surprisingly, very mixed. For some Catholic ethnic groups he is a hero, the first of a host of self-sacrificing, faithful missionaries. To others, as suggested by a resolution from the National Council of Churches of the United States in 1990, he bears significant responsibility for “genocide, slavery, ‘ecocide,’ and the exploitation of the wealth of the land.”

Catholic concern for the Americas was by no means unique to Columbus. A year after Columbus’s first voyage, for instance, Pope Alexander VI issued a bull aimed at settling the competing territorial aspirations of Spain and Portugal, the eventual effect of which left Brazil to speak Portuguese and the rest of Latin America Spanish. The pope held that the major reason to “seek out and discover certain islands and mainlands remote and unknown and not hitherto discovered by others” was that the explorers “might bring to the worship of our Redeemer and the profession of the Catholic faith their residents and inhabitants.” In 1529 Charles V, king of Spain and Holy Roman emperor, justified his sponsorship of an expedition to the New World by describing his “chief motive” as the conversion of Florida’s Indians. The Dominican priest Bartolomé de Las Casas (1474–1566), who had served as a colonial official in Hispaniola, eventually became an ardent defender of the Indians. One of his proposals to help the Native Americans, a proposal with tragic consequences, was to substitute slaves from Africa for the Indian slaves the Spanish had taken. (Las Casas later repudiated this suggestion.) He also formulated a missionary strategy of “evangelical conquest” that focused on the proclamation of the gospel while at the same time preserving the lives and dignity of the Indians. Las Casas’s fellow Dominican, Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546), a leading theologian at Spain’s Salamanca University, also defended Indian rights. Because he felt that Christian truth should affect every area of life, he offered moral guidelines for Spanish treatment of American inhabitants that helped establish modern international relations. Vitoria thought he could justify an enlightened rule of Native Americans by Europeans, but only if the rulers protected the property, the lives, and the souls of the Indians.

The cruel impieties acted out upon Native Americans by the sailors who accompanied Christopher Columbus were matched, if not necessarily excused, by the sincere piety of Columbus himself. Library of Congress

The first well-established Christian institutions in the New World came from the work of Catholics. Before the English settled permanently at Jamestown in 1607, thousands of Native Americans had become at least nominal believers under Catholic missionaries in the New Mexico territories. The first printed hymnbook in America was not the Puritans’ Bay Psalm Book of 1640 but the Ordinary of the Mass in Mexico City in 1556. It had music set beside the words, a feature the British-American hymnals would not incorporate until the eighteenth century. The Protestant impact on Canada and the United States has been great in nearly every way, but such names as St. Augustine, San Antonio, and Los Angeles; Vincennes, Dubuque, and Louisville; and (in Quebec) St. Paul-du-Nord, Notre-Dame-de-Rimouski, and St. Jean testify to the fact that Catholics were here first.

Roman Catholicism in New Spain

Spanish colonization with Spanish varieties of Christianity extended from the early sixteenth century to the early nineteenth. Unfortunately for the Native Americans conquered by the Spanish, Old World Christian ideals were difficult to translate into practical realities in the New. Conquistadors such as Cortez in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru were accompanied by priests. Although these priests sometimes protested when military rulers treated the Native Americans like animals, they could not prevent brutal exploitation of the native population. One such protest by Dominican colleagues of Las Casas in New Spain, Bernardio de Minaya and Julian Garces, led Pope Paul III to issue in 1537 a formal declaration (Sublimis Deus) affirming that Native Americans were in fact people and could indeed become Christians.

Colonial administration was heavy-handed and often displayed anything but the ideals of Jesus. Yet Spanish Catholicism enjoyed a notable history in the early days of European settlement. In 1542 the Franciscan priest Juan de Padilla became the first American missionary martyr when, having left the company of Vasquez Coronado to make a preaching tour, he was slain by Native Americans in what is now Kansas. In New Mexico, as many as thirty-five thousand Christian Indians had gathered around twenty-five missionary stations by the year 1630.

In 1634 a Franciscan, Alonso de Benavides, described to the pope what life in a pueblo was like for the overworked brothers. Since it was very expensive to bring religious workers from the old country, a single friar might be responsible for the spiritual instruction of four or more villages. The friar had to say mass, perform baptisms, and carry out other religious duties. At his residence, he would establish a school “for the teaching of praying, singing, playing musical instruments and other interesting things.” He would also instruct the Indians in raising crops and cattle because, as Benavides put it with an attitude typical for his time, “if he left it to their discretion, they would not do anything.” Benavides reported that ten Franciscans had been killed in pursuing this work but that they had become “a lighted torch to guide” the Indians “in spiritual as well as temporal affairs.”

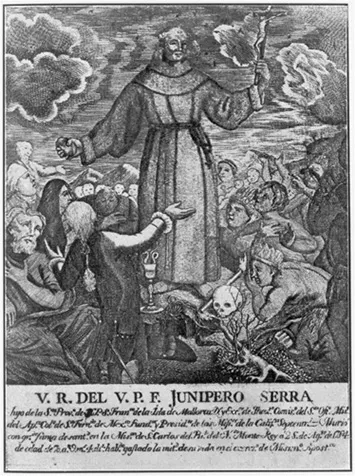

Over the next two centuries dedicated missionary activity continued in the American Southwest and in California. Franciscans such as Junípero Serra (1713–1784) took the lead in establishing a Christian presence in California. Serra had been born in Mallorca and had been named a professor in his native island when at the age of thirty-five he came to New Spain to administer the Franciscan College of San Fernando in Mexico City. Twenty years later he led the Franciscans into California. From 1769 to 1845, 146 Franciscans helped found twenty-one mission stations in that future state. Together they baptized nearly one hundred thousand Indians. Serra was patient in teaching habits of settled agriculture to his converts, fervent in promoting spiritual discipline among his fellow workers, and sharp with Spanish officials who impeded his work.

Although Junípero Serra was long celebrated, as in this icon-like illustration, recent historians have assessed more objectively the positive and negative aspects of his mission. Library of Congress

At the same time, modern Christian sensitivity about the dignity of all peoples has led to questions about Serra’s relationship with the Native Ameri...