- 781 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This standard textbook on Michigan history covers the entire scope of the Wolverine State's historical record -- from when humankind first arrived in the area around 9,000 B.C. up to 1995. This third revised edition of

Michigan also examines events since 1980 and draws on new studies to expand and improve its coverage of various ethnic groups, recent political developments, labor and business, and many other topics. Includes photographs, maps, and charts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Michigan by Willis F. Dunbar,George S. May in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

IN THE EARLY 1600s, French explorers reached the lands we now call Michigan and began to keep written records of their activities and observations in the area. Such written materials are what the historian studies. The history of Michigan, however, was conditioned by forces at work long before the seventeenth century, and without a knowledge of these forces one cannot really understand the developments of the past four centuries.

Time, as reckoned by the geologist, has little meaning to the ordinary person, who is unable to conceive of a million years, to say nothing of a billion years; yet these are the time units that mark geological ages. During these dark recesses of time when the earth was cooling, volcanic eruptions in northern Michigan brought deposits of copper to the earth’s surface that would be mined by the Indians several thousand years before the arrival of the Europeans. During these ages, deposits of iron, petroleum, and other mineral resources were also formed which would later lead to other mining activities in Michigan.

Relatively late in geological time, great icecaps covered the northern part of North America. As the climate warmed and cooled, these icecaps, or glaciers, retreated and advanced. The advance and recession of the glaciers occurred not once but four times. The underlying rock over which these great glaciers spread varied in character. A formation known as the Laurentian Shield (also called the Canadian Shield) is the most dominant feature of eastern and central Canada and extends as far south as Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. It was the earliest land mass of North America. It consisted of crystalline rocks and granites, which did not easily erode. South of the Laurentian Shield the predominant rocks were sandstone, limestone, and shale, which were much softer and hence more vulnerable to erosion. The advancing glaciers swept the Laurentian Shield bare of soil, depositing it helter-skelter over the area as far south as the Ohio River. Combined with this soil was the soil which was formed by the erosion of the limestone and shale to the south of the Shield. This resulted in the formation of a belt of fertile land for agriculture in southern Michigan and other parts of the lower Middle West, while leaving sandy soils ill suited to farming in the region that embraces the northern portions of Wisconsin and Michigan. Thus, while the glaciers were responsible for providing the basis for a prosperous agricultural economy in southern Michigan, they were also responsible for creating the conditions that have greatly retarded the development of much of the northern two-thirds of the state.

The configuration of the land of Michigan, the size and location of the lakes, islands, and peninsulas, resulted from varying degrees of resistance to erosion by different strata of rocks. The Great Lakes mark the location of weak rocks, such as limestone and shale, that were easily eroded in preglacial ages to form river valleys that drained into this region. These valleys ran parallel to the direction in which the great masses of ice in the ice ages flowed down from the north. These glaciers not only further eroded the existing riverbeds but the immense weight of the ice, which reached a maximum depth of nearly two miles, depressed the earth’s surface. While the position of the lakes conformed to the established drainage patterns of the preglacial period, their shape was also affected by the gradual rebounding of the earth’s surface, after the glaciers disappeared. The islands in the lakes are features resulting both from this rebounding action and from the fact that the islands generally rest on stronger rocks which were more resistant to the preceding eroding force of water and ice.1

The lakes that emerged after the last Ice Age and assumed their present shapes approximately 2,500 years ago have been the single greatest influence on Michigan’s historical development. In every period of Michigan history, the existence of water on all sides save one has influenced the activities of the inhabitants of these lands. The Great Lakes have provided invaluable transportation from the time of the Indian and fur trader canoes to present-day giant ore boats. The opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway on April 25, 1959, made Michigan ports on the Great Lakes available to large oceangoing vessels despite Michigan’s location deep in the interior of the North American continent, hundreds of miles from any ocean. Although the lakes have been an avenue of commerce, they also have been a barrier to commerce since they have severely limited the construction of short and efficient highways and railroad networks on adjacent lands. The lakes affect the climate and therefore the agriculture. Prevailing westerly winds blowing across Lake Michigan nurture Michigan’s fruit belt along the west coast of the Lower Peninsula. Because they are cool in the spring, these winds prevent the premature development of the fruit buds, and warmed by the lake in the autumn, these winds prolong the growing season. In addition, the lakes have been an important food source with their abundant supply of fish.

Glacial activity also scooped out the areas now covered by Michigan’s many thousands of inland lakes. The largest of these is Houghton Lake, in Roscommon County, with an area of nearly thirty-one square miles. Six others have areas of twenty or more square miles, with approximately 15,800 lakes covering two acres or more.2 The number of lakes is so great that it has been difficult to find distinctive names for all of them. Thus, Long Lake, Little Lake, Big Lake, Round Lake, Bass Lake, Mud Lake, Crooked Lake, and Silver Lake are among the names that have been used repeatedly. These inland lakes, as well as the Great Lakes, constitute one of the foundations upon which Michigan’s tourist industry is based because they offer limitless opportunities for fishing, swimming, and boating.

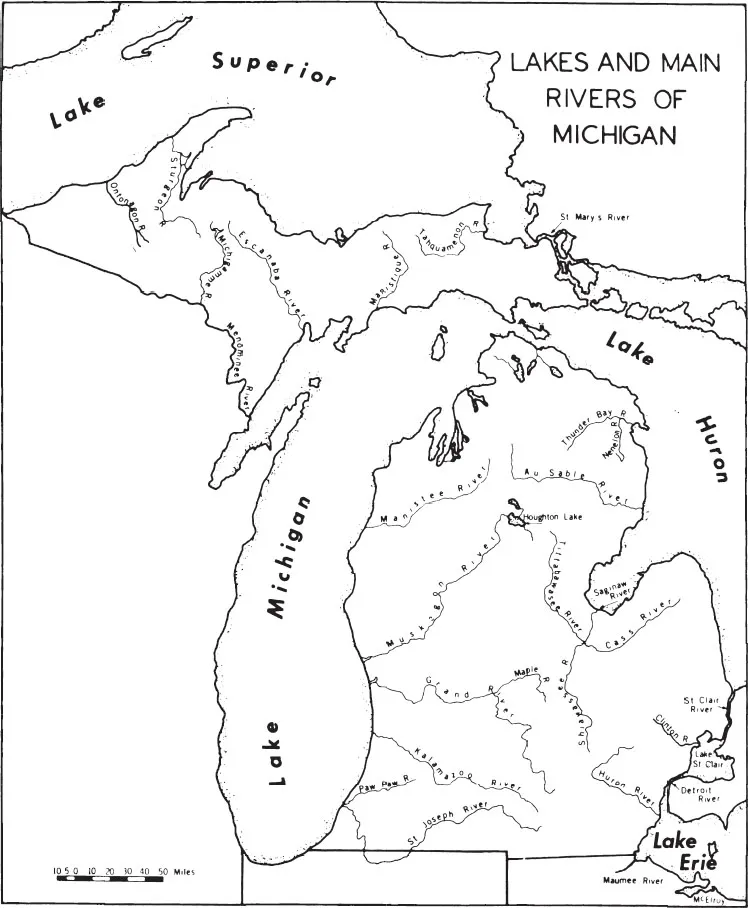

As the glaciers retreated the present river system of Michigan was created. Michigan rivers are unusual in that they are extended rivers. The surfaces of the Great Lakes originally rested at a higher sea level than at present, but after the glacial period they receded to their present levels and the rivers extended in order to flow to a lower lake outlet. The Huron River once flowed westward into other rivers that led to the body of water that later became Lake Michigan, but when the lake levels receded, it exited by way of the River Raisin to Lake Erie, and finally through its own outlet to that lake. On the western side of the Lower Peninsula nearly all the rivers have outlets that are partially dammed by sand dunes, and hence rivers such as the Kalamazoo, Black, Muskegon, and Manistee form lakes before flowing into Lake Michigan. During the great lumber boom of the nineteenth century these lakes were ideal locations for sawmills, and provided excellent sheltered harbors for various types of lake craft. Many Michigan rivers have rapids, around which many early towns originated. There are many waterfalls, nearly all of them on the rivers of the Upper Peninsula, where the most famous are the Tahquamenon Falls. The rivers were used extensively by the French fur traders and missionaries for transportation, and before the coming of the railroads they were invaluable to the American settlers. They have also been important in powering mills and at one time were a major source of electric power. In 1934 forty Michigan rivers were producing electric power at 217 sites. The greater efficiency of other methods of producing power, however, have made hydroelectric plants the size of those in Michigan an insignificant source of power, with the remaining plants of this type accounting for only 1.3 percent of Michigan’s electric energy in 1984.3 But Michigan’s rivers are second only to its lakes in the promotion of the vacation and tourist industry.

Particularly important are the three rivers that connect the Great Lakes adjacent to Michigan. The St. Mary’s River connects Lake Huron with Lake Superior, which lies twenty-two feet above the level of the lower lakes. In order for ships to pass through this waterway a canal with locks was built in the 1850s. The Soo Canal at one time carried a greater tonnage of shipping than either the Panama or Suez canals, despite the fact that it is normally closed to traffic from December to April. The St. Clair River, connecting Lake Huron with Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River, connecting the latter with Lake Erie, are similarly among the busiest waterways in the world. The importance of these rivers was recognized by the early French explorers as well as the British who followed them, for both built fortifications to control these strategic rivers and the Straits of Mackinac which link the waters of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan.

Other Michigan rivers deserve mention because of their historic associations. The St. Joseph, which rises in Hillsdale County and flows westward until it reaches St. Joseph County and then makes a southerly bend into Indiana, only to return northward and find its outlet at St. Joseph, was one of the major routes of travel for Indians, explorers, missionaries, and fur traders. Forts and a mission were built along its banks. Only a short portage had to be made to pass from the St. Joseph to the Kankakee River, whose waters flow into the Mississippi. Fur trading was also active on the Kalamazoo and Grand rivers, the latter of which is, at 225 miles, Michigan’s longest river. The Muskegon and the Manistee on the western side of the Lower Peninsula, the Saginaw and its tributaries on the eastern side, and the Menominee in the Upper Peninsula were the most important rivers for the lumber industry.

The state of Michigan, as nature made it and as it has been set off as a separate political unit, comprises an area of 96,675 square miles. This includes 38,459 square miles of Great Lakes waters, since the boundaries of the state extend out into the lakes and encompass much of Lakes Michigan, Superior, and Huron, and a small portion of Lake Erie. Michigan ranks twenty-third among the states in land area, with 56,817 square miles of land and 1,399 square miles of inland water.4 The shoreline of Michigan measures 3,121 miles, more than that of any other state except Alaska.

The name “Michigan” is an Indian word generally interpreted to mean “great water” and was first applied by the French to one of the Great Lakes which had earlier been called the “Lake of the Illinois.” Thomas Jefferson designated one of the future states that were to be created by the Ordinance of 1784 as “Michigania,” but its location was not where Michigan is today. This ordinance never went into effect, being superseded by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. In 1805, under the provisions of this act, Congress created the territory of Michigan, with boundaries considerably different from those of the state that eventually evolved from this territory Political considerations later resulted in the addition of the western portion of the Upper Peninsula and changes in the southern boundary of the Lower Peninsula. Thus the present shape and size of Michigan have been determined by a combination of natural and human factors.

The soils within the boundaries of Michigan are extremely diverse. They range in texture from plastic, compact clays to sands so loose that they are constantly shifted by the winds. The range of humus and soils containing essential elements of nutrition (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and lime) is also great. In addition to mineral soils there is a large acreage of organic soils (peat and muck) which vary widely in character. Deforestation, drainage, overcropping, and other changes wrought by humans over many centuries have greatly altered the character of the land. The sand dunes along Lake Michigan and the many swamps in the interior may have given some early visitors a false impression of the true nature of the land. Later exploration, however, revealed many areas of rich and fertile soils. Perhaps no state has such a wide variety of soils. For this reason, an unusually wide variety of farm operations came to be characteristic of Michigan agriculture.

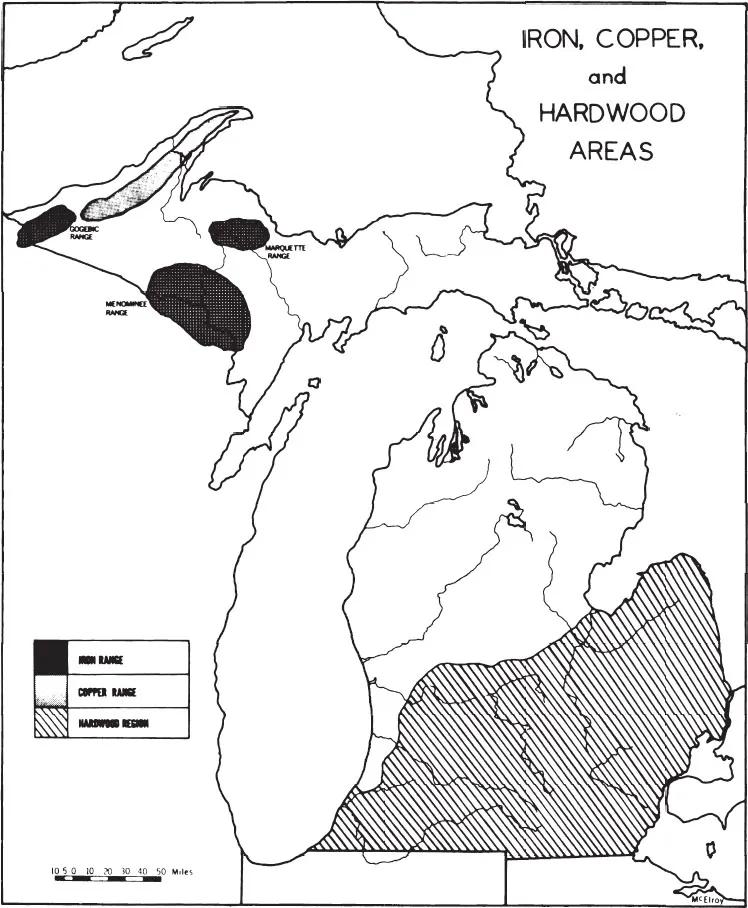

Before any farming could take place, the land had to be cleared, because except for pockets of grassland or prairie in the southern, particularly the southwestern, part of the Lower Peninsula, the land was covered with dense forests that constituted, together with the waters of the lakes, Michigan’s most visible resource. Although these forests were composed of numerous varieties and species of trees, the wooded areas lying south of a line extending roughly from the Saginaw Bay to the mouth of the Grand River included predominately hardwoods, while north of that line the forests were most commonly composed of soft, coniferous trees. The same line also roughly divided the most fertile soils of southern Michigan, which could support successful agricultural operations, from the increasingly sandy soils of northern Michigan, which generally were not suited to farming activities. Fortunately for the economic development of the northern two-thirds of the state, the trees that flourished in that areas thin soils were those that supported a great boom in lumbering in the last half of the nineteenth century.

Michigan’s greatest concentration of mineral wealth was also found in these same northern areas. Although the French and the British knew of the copper that the Indians had earlier dug out of Michigan’s soils, no large-scale effort was made to exploit this vast mineral resource until the mid-nineteenth century. The Copper Country, stretching through the Keweenaw Peninsula and southward, is located in what are now Keweenaw, Houghton, and Ontonagon counties. The three Michigan iron ranges, likewise found in the western part of the Upper Peninsula, are the Marquette, Menominee, and Gogebic ranges. Michigan also has major deposits of salt, gypsum, limestone, sand and gravel, petroleum, and coal. All would contribute to the growth of a highly diversified economy in the state.

Finally, Michigan’s climate must be mentioned as a factor in the state’s history. Michiganians,5 unlike residents of Florida or California, are not likely to boast of their climate. The weather is notoriously changeable. Climatic conditions, combined with thin soils, militate against profitable agriculture in northern Michigan. By contrast, as noted earlier, the westerly winds that moderate the climate on the western side of the Lower Peninsula are an asset to agriculture in that area. The cool breezes of summer attract many vacationers to Michigan, and the heavy snowfall and cold weather in the winter have made Michigan a major skiing and winter resort center. Thus the state’s climate, like so much of that which has resulted from Michigan’s physical environment, has been a liability in some respects, but on the whole it has proven to be an even greater asset to the state and its people.

CHAPTER 2

MICHIGAN’S FIRST RESIDENTS

BEFORE THE WHITE MAN came to Michigan the land was inhabited by people who became known as Indians. This name resulted from a gross miscalculation by the one who first made Europe aware of the New World. Columbus firmly believed that he had reached the Indies, which was the name the Europeans gave to the dimly known Far East. Hence Columbus called the native peoples in this land Indians. Like so many misnomers, this one has persisted.

The Indians whom the French found in Michigan over a century after Columbus were descendants of peoples that had arrived here at an earlier time. Where they came from, when they arrived, and who they were have been and will continue to be subjects of controversy. Although all of these questions may never be answered in an entirely satisfactory manner, much of what passed for answers in the past has had to be discarded or greatly revised by recent findings. With regard to the first question, the most common assumption remains that the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere originally came from Asia by way of the Bering Straits, where at times in the past the two hemispheres have been joined by a land bridge. Even today the narrow waterway is not great enough to prevent Eskimos on either side from traveling back and forth in their comparatively primitive vessels.

The development of new, more accurate methods of determining the age of some kinds of archaeological discoveries, beginning with the radiocarbon method perfected in the 1940s, has resulted in important changes in the dating of known prehistoric Indian sites and has pushed farther back in time the period in which these peoples were first thought to have arrived in this hemisphere. More recent discoveries have suggested that even these revised estimates were too conservative as finds in California and Mexico and elsewhere raised the possibility that humankind had been in those areas as far back as 100,000 or even 250,000 years ago, rather than the 20,000- to 40,000-year range that previously had been assumed.1

In the case of Michigan, and much of the northern part of North America, however, the possibilities for discovering evidence of human existence are limited by the fact that approximately 18,000 years ago these areas were largely covered by the glaciers of the last great ice age which made the region uninhabitable. Furthermore, the immense weight of these glaciers, thousands of feet thick, ground out all surface evidence of prior life in these lands. In approximately 11,000 B.C., a warming trend initiated a northward retreat of the ice which led to a restoration of life to the uncovered surfaces. Animals moved in to feed from the vegetation that grew up again, and soon people, who lived by hunting these animals, also arrived.

Although conditions in the extreme southern part of Michigan might have supported human life as early as 13,000 years ago, the earliest evidence of such life thus far uncovered is the Gainey Site in the Flint area that archaeologists believe is perhaps 11,000 years old, or, in other words, that dates from about 9,000 B.C.2 The archaeological evidence from this a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface

- 1. The Physical Environment

- 2. Michigan’s First Residents

- 3. The French Explorers

- 4. Michigan under French Development

- 5. Michigan under the British Flag

- 6. Michigan and the Old Northwest, 1783-1805

- 7. Michigan’s Troubled Decade, 1805-1815

- 8. Exit the Fur Trader; Enter the Farmer

- 9. The Era of the Pioneers

- 10. Political Development and Cultural Beginnings

- 11. A Stormy Entrance into the Union

- 12. A Cycle of Boom, Bust, and Recovery

- 13. Out of the Wilderness, 1835-1860

- 14. Michigan Leads the Way in Education

- 15. Politics in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Michigan

- 16. Michigan and the Civil War

- 17. The Heyday of the Lumber Industry

- 18. The Mining Boom

- 19. An Expanding Transportation Network

- 20. Citadel of Republicanism

- 21. The Growth of Manufacturing

- 22. Michigan and the Automobile

- 23. Progressivism and the Growth of Social Consciousness

- 24. World War I and Its Aftermath

- 25. Michigan Becomes an Urban State

- 26. Depression and War

- 27. The Postwar Years

- 28. Years of Change and Turmoil

- 29. The Enrichment of Cultural Life

- 30. Toward a New Century

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

- Notes