- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The architectural development of Georgia Tech began as a core of Victorian-era buildings sited around a campus green and Tech Tower. During the subsequent Beaux-Arts era, designers (who were also members of the architecture faculty) added traditionally styled buildings, with many of them in a pseudo-Jacobean collegiate redbrick style. Early Modernist Paul Heffernan led an architectural revolution in his academic village of functionalist buildings on campus--an aesthetic that inspired additional International Style campus buildings. Formalist, Brutalist, and Post-Modern architecture followed, and when Georgia Tech was selected as the Olympic Village for the 1996 Summer Olympics, new residence halls were added to the campus. Between 1994 and 2008, Georgia Tech president G. Wayne Clough stewarded over $1 billion in capital improvements at the school, notably engaging midtown Atlanta with the development of Technology Square. The landscape design by recent campus planners is especially noteworthy, featuring a purposeful designation of open spaces, accommodations for pedestrian perambulations, and public art. What might have developed into a prosaic assemblage of academic and research buildings has instead evolved into a remarkably competent assemblage of aesthetically pleasing architecture.

Information

One

GEORGIA TECH

HISTORIC DISTRICT

HISTORIC DISTRICT

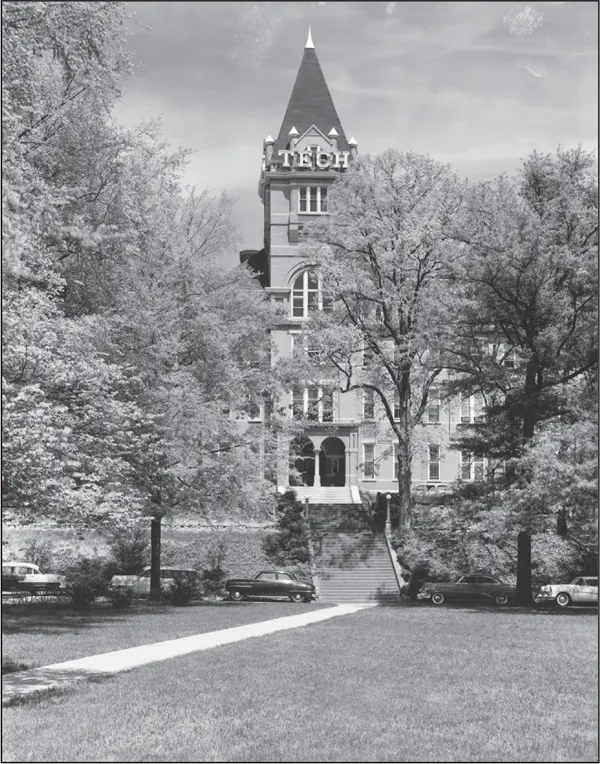

The earliest buildings of Georgia Tech, recognized in 1978 as a National Register Historic District, occupied a nine-acre campus on which gradually arose late-Victorian administration and shop buildings, an industrial textile mill structure, a library and a chemistry building both ennobled by classical ornament, a dormitory and an electrical engineering building west of an open green, and a student residential building with small gymnasium (now razed) east of Tech Tower. Indeed, the first (1896) on-campus housing for students (adequately primitive to be nicknamed “the Shacks,” now razed) had no running water, electricity, nor a kitchen. Athletics were provided for on an adjacent and uncultivated field called “the Flats,” full of ankle-twisting depressions, inhabited by rabbits and snakes, and likely accounting for Georgia Tech’s cumulative record before 1901 of winning only two football games since intercollegiate competition began in 1892. The early campus was dominated by the two, originally towered, structures, the 1888 Administration Building (Tech Tower) and the adjacent and contemporary Shop Building; the latter was destroyed by fire in April 1892, immediately rebuilt without its tower in 1892–1893, and finally razed in 1968.

Atlanta architects Bruce and Morgan gave several southern schools a similar start during the same late-Victorian period, erecting brick and often towered administration “main” buildings at Agnes Scott College (1889–1891), Auburn University (then Alabama’s Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1889–1890), Clemson University (1891–1892), and Winthrop College (1894–1895), with the latter two in South Carolina. This whole group may derive from Gottfried Norrman’s 1882 Stone Hall (later Fountain Hall) at Atlanta University, although Georgia Tech’s administration building is more ordered and boasts a more articulated upper tower.

The “historic” Georgia Tech reflected prevailing dichotomies of the times: a “New South” spirit that called for a rigorous encouragement of industry in a region traditionally lacking technological advancement; an engineering school newly planted in a growing metropolis at the heart of the South, an essentially rural region whose cotton economy, for generations, had fed northeastern US and English textile mills, not southern and regional mills; and an institutional architecture of masonry in a city whose prevailing buildings were wood-framed. Moreover, in Atlanta (and throughout the South), architects were mostly imports from other states and countries; no professional architecture degree-granting schools existed in the South before 1907 (Auburn) and 1908 (Georgia Tech and Tulane), although some coursework toward a degree in architectural engineering existed at Tulane in New Orleans as early as 1894.

Founded on October 13, 1885, and named the Georgia School of Technology, the state engineering school completed its administration/academic tower and shop building in 1888, marking the opening of the institution, a school initially granting only a baccalaureate degree in mechanical engineering. Degrees in electrical, civil, textile, and chemical engineering were added by 1901, and the “North Avenue Trade School” was born. The school buildings of Georgia Tech’s historic district reflect this early curriculum and established the institution that would become one of the leading engineering and research institutions in the country.

Two of Atlanta’s most prominent architectural firms, Bruce and Morgan and Walter T. Downing, produced Georgia Tech’s earliest buildings. Bruce and Morgan’s experience in building towered county courthouses (Walton, built in 1883, and Newton, 1884) may have influenced their selection to design Georgia Tech’s and Agnes Scott College’s first academic buildings and Tech’s Shop Building. After the college work, the firm would follow with additional county courthouses of like Victorian character (Floyd, 1892; Paulding, 1892; and Monroe, 1896) and further advanced their reputation as designers of prominent public buildings with their design for Concordia Hall (1892–1893) in Atlanta. Their early skyscrapers in the city include the Austell Building (1896–1898, razed), the Prudential/W.D. Grant Building (1898), the Empire Building (1898–1901), and the Fourth National Bank (1904–1905, enlarged and then remodeled) and their turn-of-the-century work also includes churches such as North Avenue Presbyterian (1900) and All Saints Episcopal (1904–1906) as well as neighborhood fire stations (No. 6 in 1894 and No. 7 in 1910). Morgan and Dillon’s 1907 Carnegie Building for Georgia Tech served as the school library for 46 years.

Real estate developer Edward Peters, in the 1880s, had provided the land for the engineering school’s campus, and just to the east of the site, Peters was already developing a residential district (now “midtown” along Peachtree Street and Piedmont Avenue) where Bruce and Morgan designed several prominent and still extant residences. However, the most prominent late Victorian architect of “artistic homes” was W.T. Downing, Georgia Tech’s second significant architect during its formative years and designer of Georgia Tech’s Swann Dormitory and the [Savant] Electrical Engineering Building (both, 1901). Downing had established his own firm in 1890 and found his first success in winning the competition for the Fine Arts Building for the Cotton States and International Exposition held in Atlanta in 1895. Downing also excelled in church design, including the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, 1897; Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church, 1911–1912; and First Presbyterian Church, 1915–1919), all three in Atlanta. In 1913, W.T. Downing collaborated with Bruce and Morgan in the design of the Gothic Revival Healey Building, a 14-story tower in the Fairlie Poplar district of Atlanta.

It was Thomas Morgan, the first president of the Atlanta chapter of the American Institute of Architects (1906), who promoted the idea that the Georgia School of Technology should establish an architecture school, a proposal that came to pass in 1908.

Georgia Tech’s historic district thus features the work of the city’s best architects of the era. They were not native Atlantans, however; Downing was born in Boston, Alexander Campbell “A.C.” Bruce was born in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Thomas Morgan was born in Manlius (Syracuse), New York. In 1909, another out-of-towner, Francis Palmer Smith from Cincinnati, would arrive and change the course of Georgia Tech’s and Atlanta’s architecture.

ADMINISTRATION BUILDING AND SHOPS BUILDING. Built in 1888 by architects Bruce and Morgan, Georgia Tech’s “main” academic/administration building, with its complementary wood and machine “shops building,” reflected the philosophy of Tech’s educational system in the early years—equality between the shop and academic curricula. The students and faculty worked under a contract system, competing with local contractors and providing an important source of revenue for the school. (GTA.)

ACADEMIC BUILDING “TECH TOWER,” 1888. Tech Tower featured the kind of late-Victorian masonry architecture familiar in Southern courthouses and collegiate “mains” of the period, many designed by Bruce and Morgan. Red brick with decorative corbels, terra-cotta insets, limestone lintels and bands, and contrasting white window trim set the precedent for redbrick masonry buildings, which continued to characterize Georgia Tech’s campus architecture for decades to follow, albeit in varying styles. (GTA.)

THE (REBUILT) OLD SHOPS BUILDING, 1892. The 1888 shops building was destroyed by fire in 1892 and immediately rebuilt without its tower. The façade was a balanced composition with central pediment over a projecting central bay; the strong and deep arched entry recalled 1880s work by Henry Hobson Richardson while the classical character looks forward to the Lyman Hall Chemistry Building that would be erected 14 years later (1906). (GTA.)

SHOPS BUILDING INTERIOR. With similar interior features, including a foundry and machine shop, with a woodshop wing behind, the rebuilt shops building continued contract production, including iron columns for Grant Theater and gates for Oakland Cemetery. After disputes arose with local labor unions, the contract system was abandoned. The rebuilt shops were finally demolished in 1968, its site marked today by the Corliss Pump (steam engine) and Harrison Square. (GTA.)

KNOWLES DORMITORY, 1897 (RAZED). The first student housing utilized temporary frame “shacks” retained for a short period on the land donated for the school. In 1897, a more-permanent brick building, Knowles Dormitory, was erected, including a dini...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Georgia Tech Historic District

- 2. Architecture under Francis Palmer Smith and John Llewellyn Skinner, 1909–1925

- 3. Traditional Architecture under Harold Bush-Brown, 1925–1939

- 4. Paul M. Heffernan’s Functionalist Academic Village, 1946–1961

- 5. From School to College of Architecture, the 1960s–1994

- 6. Architecture during G. Wayne Clough’s Presidency, 1994–2008

- 7. Contemporary Architecture, 2008–Present

- 8. Architecture of Athletics

- 9. Fraternities and Sororities

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Georgia Tech by Robert M. Craig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.