- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lost Towns of New England

About this book

New England is home to abandoned towns and forgotten main streets that once bustled with life and commerce. From villages sunk underwater to cities undone by the rise and fall of mill life, madness or just plain bad luck, these ghost towns offer a unique look into the rich history of the past. Get a glimpse into what early life was really like through historical accounts of abandoned villages. Discover the history behind the ruins of towns like Connecticut's religious community Gay City, the former New Hampshire resort town of Unity Springs and Massachusetts's famed Dogtown--before nature reclaims them entirely. Join local author Renee Mallett as she uncovers the heydays of some of New England's most fascinating lost towns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lost Towns of New England by Renee Mallett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

LOST

Abandon [uh-ban-duhn]

verb (used with object):

To leave completely and finally; forsake utterly; desert:

to abandon one’s farm;

to abandon a child;

to abandon a sinking ship.

To give up; withdraw from; discontinue:

to abandon a research project;

to abandon hopes for a stage career.

to give up the control of:

to abandon a city to an enemy army.

—From www.Dictionary.com

1

HARD TIMES IN THE MILLS

Industrialization began in earnest in England but came relatively early to the New England states. The same plentiful lakes and rivers that tourists love today were originally the early powerhouses of the mills that sprang up with increasing frequency in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Samuel Slater, a British engineer, got a group of Rhode Island businessmen to fund the first mill in the United States in the 1790s. By 1812, nearly one hundred mills had popped up around this part of the country. With lots of running water and, later, steam to power machinery, the mills quickly grew into important centers of New England life.

The earliest of New England’s mills were fairly small compared to what they would grow into later. Most employed fewer than seventy people and relied on family units as blocks of employees. These family units acted as early transitions from the family farms to the mills. The father would be the “manager,” who oversaw the work done by his wife and children. But this system quickly fell by the wayside as the mills grew larger and employed more and more people in a relatively short amount of time.

Many everyday items that were originally made by hand on individual family farms or made for a price by a skilled craftsman could suddenly be made relatively quickly and very cheaply in the mills. This was both a blessing and a curse. Skilled craftsmen were suddenly squeezed out of the market. But items that were once only available to the wealthy were suddenly in reach of more and more people. And people who were not landowners themselves had more job opportunities than they had previously. As much uncertainty as industrialization brought, it was still a welcome change for many.

Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was the first successful cotton mill and paved the way for further industrialization in New England. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Young women were among the first benefactors of the switch from an agricultural system to an industrial one. Instead of living their lives on the farm—first their fathers’ and then their husbands’—many moved to bigger cities and got jobs independent from their family for the very first time. But of course, they did not have real freedom as truly independent ladies. Knowing that their families would worry about the mill girls becoming too urbane and modern, many of the factories set strict protocols for the unmarried women who sat at their looms. Swearing was often forbidden, church attendance was mandatory if they were not scheduled to work and most of the girls lived in company-owned boardinghouses that were strictly female-only, with curfews and no male visitors allowed.

That’s not to say there weren’t any benefits for the traditional New England farmers as well. The dawn of the mill era coincided with the rise of the huge midwestern farms. The small family farm of the Northeast couldn’t compete with the massive amounts of fresh food that the very large and very fertile land in the middle of the country could produce. People who had been part of farming communities for generations then had the option of mill work or switching their farming practices to support the demands of the mills. While everything from clock parts to paper were made in New England’s mills, much of the work centered around the textile industry. Local farms could switch to raising sheep and find buyers for the wool roving as close as the next closest city with a mill.

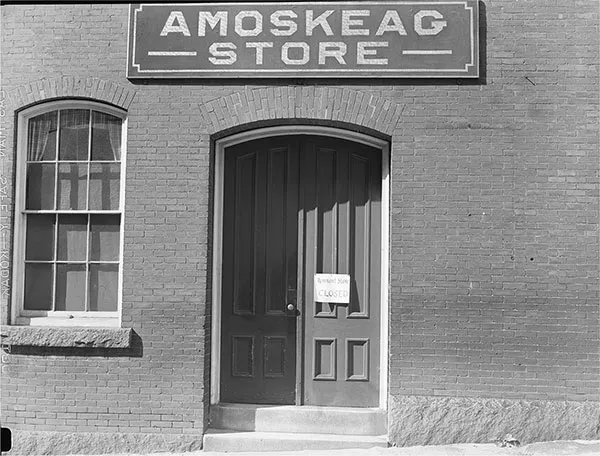

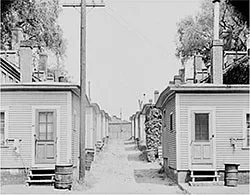

The mills didn’t just change life on the farms, they changed city life as well. Seemingly overnight, a small village could become an important urban center with the addition of a mill. By and large, these were all company towns. The residents worked in the company mill, bought everything they needed at company stores and brought those goods home to the houses they rented from the same company. Oftentimes, millworkers were not paid in actual cash. The company that owned the mill would instead pay them in credit that could be given back to the same company as rent for their homes or goods from their stores.

This same convenience was, for some places, also their downfall. When an entire town was owned—from the roads to the jobs—by one company, the future of everyone rested on the company’s shoulders. If the mill failed or the company that owned it went under, it could spell disaster for everyone. With so much of New England life centering around the mills, it should come as no surprise that they caused nearly as many ghost towns as they caused towns to thrive. Across the Northeast, you can find the remains of many towns that were done under when the mills went belly-up.

Mill girls at work in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1912. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Amoskeag Company Store in 1936 in Manchester, New Hampshire, was owned by the same company that owned the mills and rented housing to the mill workers. Photograph by Carl Mydans, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Company-owned housing in 1937. Small homes, such as these built and owned by Manchester, New Hampshire’s Amoskeag company, were rented to their workers. Photograph by Edwin Locke, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

DANIELS VILLAGE, CONNECTICUT

Gristmills, though still in use today in a more mechanical form, are probably more or less unknown to the average modern-day reader. Even though the image of a gristmill with a large wooden waterwheel is a familiar one, few seem to know their purpose. They are one of those things that were of vital importance to our ancestors that we give almost no thought to today. Even if most people can’t name what the building does, we all seem to share a collective memory of the iconic waterwheel spinning away on a historic building.

What those wheels, powered by the flow of water, were busy turning were two colossal millstones inside the building. The enormous weight of the stones turning would slowly grind grains and corn into cornmeal or flour. It was a tedious process that took a great deal of time and effort to do by hand and one that could be done relatively easily with a gristmill. This made the mills important centers of industry and community for our ancestors. Fortunes rose and fell with the success of a gristmill, not just for the mill owners, but for everyone in the surrounding community who relied on it.

In this case, the entire inception of a town can be credited to the construction of a gristmill. The land along the Five Mile River was originally owned by John Fiske, who was a reverend in the nearby town of Killingly, Connecticut. Over the years, Fiske slowly sold off some small parcels of land. Each land sale resulted in a new family moving in and building up farms. But the population boom came about when one of these new transplants, Jared Talbot, who had a small stretch of land along the Five Mile River, built the first gristmill in the area around 1720.

With the hard and tiresome labor of grinding corn able to be done by the mill, people began moving into the area in a steady stream. In 1760, Jared Talbot would take on a business partner and add a sawmill, tanning operations and a boardinghouse near the Talbot Mill. In time, the area around Talbot Mill came to be known as the village of Talbot’s Mills. The town had its own school, a cider press and easy access to the surrounding area, thanks to an extension of the Stone Road, which first began to make its way through the area in the early 1700s and can still be seen today.

In 1814, the town had become enough of an industrial center that several businessmen from Rhode Island went in together and built a large cotton mill to go with the other factories that were already chugging along at Talbot’s Mills. The Rhode Island entrepreneurs named their new business Howe’s Factory and poured great sums of money into the venture. They moved the original gristmill that was built back in 1720 away from its original location so they could dam the river and add in a new hydraulic system to power their cotton mill. A large blacksmithing operation was added to support whatever tools or repairs the cotton mill needed. They also put in a long line of tenement houses to rent to the workers they would employ at the mill. In order to carry out such a massive undertaking in an already well-established township, the men from Rhode Island convinced many of the existing local landowners to sell their parcels to them for a premium price.

This first consolidation of the town made it very easy for the Daniels family to come in thirty years later and buy nearly all of Talbot’s Mills in one fell swoop. They owned the gristmill, the cotton mill, the blacksmith shop and pretty much everything else. Changing the name of the town from Talbot’s Mills to Daniels Village seemed the next logical step.

The Daniels family owned the town for less than half the time that the Rhode Island developers had. In a sudden stroke of bad luck, the cotton mill burned in 1861. While the family debated over whether to rebuild or try their hand at something new, the residents of Daniels Village wandered away, one or two families at a time, looking for work in the many of the other mills that had popped up throughout New England in recent years. The family put the town up for sale, from the stone dam to their own spacious family home, and waited for a buyer who would be interested in buying the whole thing at once—the same way they had sixteen years prior. The Daniels would have to wait until 1880 for a buyer to come along that would be interested in buying a town that had no residents and no industry.

Even as early as 1915, accounts say that Daniels Village had been reduced to something less than a ghost town. The stone mansion where the mill manager had lived was still standing, along with the stone dam that was built to power the cotton mill that no longer existed. Nearly everything else had been reduced to nothing more than cellar holes.

It is not all that different from what can still be seen when visiting Daniels Village today. The stone house, now a private residence, still sits boldly at the corner of Stone and Putnam Roads. The local preservation commission holds an annual history walk that makes stops along the Stone Road to view the cellar holes. The rest of the year, this privately held land is an active and ongoing archaeological dig—same as it has been since the early 1980s. Daniels Village was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

LIVERMORE, NEW HAMPSHIRE

While anyone looking into the past of Livermore, New Hampshire, will find an abundance of playful, if somewhat awkward puns, trying to rhyme “Livermore” with “never more” or “forever more,” a more serious recorded history of this once-thriving town is harder to find. Located about sixteen miles west of North Conway, just a few miles from Bartlett, the former village is now part of the White Mountain National Forest.

A lithograph of Statesman Samuel Livermore. His granddaughter would name a town after him. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One thing that is not a mystery is the origin of the town’s unusual name. In 1874, a lumber operation named the Grafton County Lumber Company was started in New Hampshire’s north country by two brothers, both Boston lawyers, named Daniel and Charles Saunders. Livermore is the town that sprang up to support the workers of that lumber company. The brothers named the town after Samuel Livermore, a New Hampshire state senator who was also the beloved grandfather of Daniel Saunders’s wife.

If anything can be said of the Saunders family, it’s that they had impeccable timing. They were able to buy a vast amount of north country land very cheaply in 1874 due to the relative remoteness of the property. But in 1875, the Sawyer River Railroad was created. Although it was only eight miles long and created almost solely to haul lumber, and the occasional passenger, the railroad served to immediately tie the village to the surrounding area. The Grafton County Lumber Company, helped along by the railroad, did so well that within just one year, a town had sprung up to support the workers. When the first sawmill burned in 1876, residents built two additional mills to replace it within a year’s time.

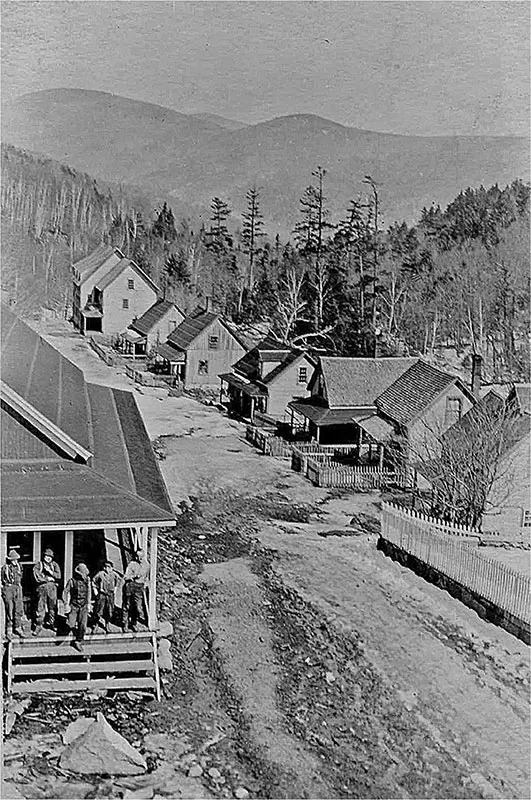

In 1885, the town had 153 residents, 28 of whom were children, plus an always changing number of lumberjacks and the like who would come to work for just a season and then move on to the next project somewhere else. The one school in town was valued at $151, from the building down to the books. The two schoolteachers were paid $26 a month to teach all 28 children together in one room.

Livermore was, from start to finish, a true company town. The Saunders family built and rented out the homes in town. The Saunderses themselves only lived in town part time, but they made sure they had stately accommodations for when they were there. Their own home, a sprawling Victorian manse, with twenty-six rooms, three chimneys, two wide wraparound porches and more peaked roofs than a modern-day McMansion, was the largest building in town outside of the sawmills. The Saunders family owned absolutely everything if you traced it back far enough. The largest store in town, where you could buy anything and everything from a dress to wear to church to the family groceries for the week was the Livermore Company Store. But even the smaller specialty shops in Livermore were all company stores, owned by the logging company, and buying outside of town was quite definitely frowned on. One enterprising store owner in the neighboring town of Bartlett would bring a wagon packed with groceries in the dead of night to the top of Livermore Road. Thrifty town residents could buy produce from the back of his wagon under the cover of darkness.

The main street of Livermore. In the far back is a glimpse of the Saunders mansion. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Bargain hunters weren’t the only Livermore denizens to be found sneaking down the road out of town in the dead of night. Logging was hard and dangerous work. Oftentimes, the men in the camps were not experienced lumberjacks. Farmers who were looking to make money through the winter months, young men who were looking to leave the family farm or recent immigrants who had a hard time finding work elsewhere would sign on for a season and then decide the sparse and filthy life in the camp was not for them. Defection became enough of an issue in Livermore that the Saunderses hired a man named Sydney White to track down those who left before their contract was up. One night, White confronted one of these runaways and ended up shooting him in the leg. A closely watched court case followed that resulted in a $3,000 fine for the Grafton County Lumber Company.

Unlike most of the timber operations of the time, which clear-cut forests as quickly as possible, the Saunderses believed in sustainable logging. Only select trees of a certain age, kind and size were allowed to be harvested. This ensured that, over the course of many years, there would always be more trees to cut. The system also allowed for the natural checks and balances of the forest ecosystem to remain in place. While most of the woods owned by New Hampshire’s lumber barons would fall victim to massive forest fires over the years, the land around Livermore never had the same problem. While the forward-thinking policies of the Saunders brothers should have kept the town of Livermore a profitable place to live for many generations, there were some things that they could not control.

While the forests around Livermore never burned, the sawmill did. In 1909, an accident in the mill caused a large portion of the structure and a large stockpile of lumber to be damaged. That same year, a fire damaged part of the Saunders mansion. In 1917, Daniel Saunders passed away. Charles finished rebuilding the sawmill, but in 1920, human error would cause it to burn for a second time. This time, it was a total loss of the building. It would be two years before the rebuilding of the sawmill would be completed, but during that time, Charles passed away as well.

The company was already on shaky footing before the death of Charles Saunders. Several years of low to no output from the damaged sawmill, plus the high cost of repairing and rebuilding it, meant there was not much of a financial cushion when Charles died. The company and the town of Livermore were left to three younger Saunders sisters, who had no experience in the timber industry or in running a business at all.

Even still, Livermore might still be a town today had an early nor’easter not come through the area in November 1927. Although the town of Livermore was perched high above sea level, the much higher elevations of the mountains surrounding it, like Mount ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART I. LOST

- PART II. FOUND

- Bibliography

- About the Author