This book is available to read until 7th February, 2026

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 7 Feb |Learn more

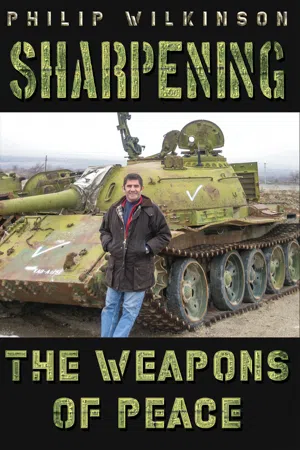

Sharpening the Weapons of Peace

About this book

Colonel Wilkinson spent 31 years in the British Army with the Royal Artillery, commando and parachute brigades and special forces. In his last job in the army, he was the principal author of the first British Joint Warfare Publication (JWP 3-50 Peace Support Operations). During his military service he gradually came to the understanding that the achievement of peace required a comprehensive approach that addressed the causes and consequences of conflict and not just the symptoms. These thoughts were crystallised during his four years as a senior research fellow at the Centre for Defence Studies at King's College, London. After King's College, he was deployed as the international advisor to President Kagame in Rwanda for one year and President Karzai in Afghanistan for two years before supporting the National Security Advisor in Baghdad for three years. More recently, he spent fifteen months in the occupied Palestinian territories before deploying to Somalia for three years to support the President and Minister of Internal Security. These positions have given Colonel Wilkinson a unique perspective of international intervention operations. Many others have written of their observations from the outside looking in, Colonel Wilkinson has had the privilege of being part of the host government looking out. Many may find his observations unsettling!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sharpening the Weapons of Peace by Philip Wilkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

On 17th of November 2015 in Geneva, to celebrate their 20th anniversary, Interpeace, an international peacebuilding organisation and strategic partner of the United Nations, organised a public debate entitled, ‘Cancel the cruise missiles: military intervention cannot build peace between warring parties’. The speakers against the motion were Colleen Graffy, an American associate professor of Law at Pepperdine University in London and Oliver Kamm a British leader writer and columnist for the Times and author of Anti-Totalitarianism; The Left-Wing Case for Neoconservative Foreign Policy. Supporting the motion were Ruben Zamora the Ambassador of El Salvador to the United Nations and me, Philip Wilkinson, a retired Colonel from the British Army and academic from King’s College and Chatham House, London, who since 9/11 had worked as a security policy advisor to the governments of Rwanda, Sri Lanka, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia.

Interpeace Conference Geneva 17 November 2015

I started my presentation in Geneva as follows: “Please don’t think that I am some sort of limp liberal, I have been shot at and shot back with lethal intent against people who were trying to kill me in several countries; however, I believe passionately that cruise missiles and military force alone cannot build peace between warring parties.”

Interpeace conference, me at the lecture making my point.

In this memoir, I want to trace two inter-related themes relating to that statement; first, how did someone from my disadvantaged background transition to this stage in Geneva and second, what were the operational lessons and personal experiences that have led me to take this ethical stance. How did I morph from robust tactical practitioner to strategic thinker and principal author of the national security policies of Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia?

This then is not another biopic of an army officer’s son who rose to high military rank but the story of a boy from the slums of Liverpool who, by force of character, transitioned relatively successfully through a series of extraordinary international challenges to that stage in Geneva and beyond. It is not a story of arrogance disguised as humility, but one of continual amazement at my luck and good fortune. I certainly never set my sights on the successes that I have achieved, but progressed slowly and incrementally through life thinking that every step forward was as far as I would go.

As an individual, perhaps the most important lesson that I have learned is that we always have the ability to develop further. You could have knocked me over with a feather if you had told me when I first joined the army with two low grade A-levels that later in life I would spend four years as an academic at King’s College London or that I would have a series of heads of states and ministerial level friends in far off countries.

This is not then a story of disguised personal ambition but of wanting to play a part, albeit a leading part in making things better for other people. It is a story of how I learned to use every means of hard and soft power that I perceived as possible, not to win the war but to try and win the peace. It is a story of how I spent fifty years of my life trying to sharpen the weapons of peace. I hope that does not sound too pompous or sanctimonious. I know that I have upset plenty of people along the way, usually those in more senior positions than myself or working in large, and what I considered, ineffective institutions and bureaucracies such as the United Nations. Part of my problem is that I have an almost uncontrollable urge to point out the obvious and to make it clear when the Emperor is not wearing any clothes. But I would like to believe that it is because I have taken a principled position, even often at the expense of my own career advancement or financial gain, that I have had the successes that I have.

My story starts in Liverpool where my parents first tried to settle after the Second World War. My father, who had served in the Royal Navy was a proper scouse, whereas my mother, who served in the Women’s Royal Air Force, came from a military background. I was their second son.

When I was three years old, my father moved the family South, to Newbury in search of work. We initially lived in a two up and one down cottage with an outside toilet in Shaw on the banks of the River Lambourne. After three years, we moved to a brand-new 3-bedroomed council house that, at the time seemed like a palace, and my parents lived there until they died in their 90s. I did okay at school and managed to follow my older brother into the local grammar school. We had a younger brother and sister by then. We were happy but life was not easy, money was always in short supply. Dad was a painter and decorator; mother had a job as a school cook. It was a life of school trousers that were too short and hand-me downs. Holidays were almost non-existent and I was often left feeling the poor relative when compared with my mainly more middle-class school chums in St Bartholomew’s Grammar School. I knew that to succeed in life, like every other sensible young person, I would have to work hard, not only in the class-room but also at everything I did.

Looking back, what is certainly true is that my background has given me a different social frame of reference to many of my military colleagues and more affluent and privileged friends. I guessed that my life was going to be a struggle. I did not mind that as I felt well able to cope with the challenge but I did learn to despise the sense of superiority and entitlement that does, even now, still resonate far too often in our society. I have been told more than once that I am a chippy old git. I might take issue with the ‘old git’ bit but ‘chippy’ probably does describe some of my prejudices. Joking aside my determination to have my say and not necessarily confirm to the ‘club rules’, or even pretend to want to join the club, did without a doubt hinder my military career; but fortunately, not my second civilian career.

In 1969, I decided to have a crack at the Army Commissioning Board and to try to become an army officer. I spent 32 years in the army and finally made colonel in rather dubious circumstances. My military career consisted of three distinct phases. In the first phase, apart from the odd course here and there, until my mid-30s, having joined the Royal Artillery I served with the commando and parachute brigades and commanded a detachment of Special Forces in Northern Ireland. After Special Forces, I completed a second two-year tour in Northern Ireland as a senior intelligence officer with responsibility for half of the province. During this phase, when I was not trying to be a tough and special soldier, I was playing rugby and enjoying my life as a fit and robust bachelor. While a large proportion of the British Army postured on the inner German border drinking copious amounts of duty-free alcohol, driving duty-free cars, running horse shows and getting promotion, I packed in as much operational experience as I could. I was not particularly impressed with the social niceties that seemed to drive many of my peers. I loved my first 15-years of service in phase 1 and worked with some outstanding and professional officers, senior non-commissioned officers and soldiers. In 1983, after my second two-year operational tour in Northern Ireland with special forces and the intelligence community, I was persuaded to re-join main stream soldiering and revert to the conventional Royal Artillery. This was the start of the second phase of my military career. From that time, whilst I still loved working with soldiers, I gained little professional satisfaction.

Fortunately, by now I was married to Ruth and had a family life to compensate for my lack of professional satisfaction. When I met Ruth, she was at Sussex University, studying geography and was about to enter the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. Ruth had managed to win a full officer’s scholarship. To my huge good fortune, Ruth accepted my marriage proposal and gave up her Royal Naval aspirations. I have no doubt, from her subsequent successes in business that Ruth would have been the first female admiral had she joined the RN. Although, fifteen years younger than me, Ruth’s style, social flare and common sense largely compensated for my social gaucheness, and when we were joined by our son Oliver and daughter Sophie, their presence compensated for my lack of professional military satisfaction. It was as if having a lovely wife and family allowed, and encouraged me, to re-join normal society. The third phase of my military career I spent as a teacher and doctrine writer, which I did enjoy. At the culmination of my career, I wrote not only the first UK joint doctrine manual – Joint Warfare Publication 3-50 Peace Support Operations but also most of the NATO and African Union PSO manuals. As an aside, I also wrote a series of published academic papers all of which I entitled ‘Sharpening the Weapons of Peace’.

During much of my military career, I found many of my brother officers conventional in the extreme and with little interest in enhancing their professional knowledge or skills. Even relatively senior officers often seemed proud that they had never read a military doctrine manual or even knew what doctrine was. Life in the officer’s mess in the conventional army, seemed to focus more on social events, being a jolly good chap and cosying up to senior officers. There were few, if any, professional challenges; field training exercises were the same every year and attempts to introduce realism were frowned on as ‘cowboy’.

If the focus in the first third of my professional life was military operations, the final third was to be focused on winning the peace. I have always seen war and peace as being on the same spectrum of activities, albeit at different ends, and over the 50 years of my professional life, I have travelled that spectrum. While many might disagree, I have never had any doubt that a thinking soldier can also make an excellent peacemaker. In much the same vein, I believe that private security companies that are staffed mainly by ex-soldiers can be just as adept at humanitarian and development activities as agencies from the United Nations and the humanitarian community. While many from the UN and humanitarian community might take a holier than thou attitude to the military and private security companies, I have seen first-hand on far too many occasions just how unethical UN agencies can be when chasing donor funding. The hypocrisy can be astounding and I have witnessed the UN and humanitarian agencies actively subvert one another’s programs in order to gain access to funding. At least private security companies are honest about their motivation and they are inevitably far more cost effective as a consequence.

Joint Warfare Publication 3-50 Peace Support Operations was the first ever joint publication produced by the British Armed Forces. This was the result of four years’ work and led to me joining The Conflict Security and Development Group at Kings College London.

The 20th of December 1999 was my last day in the army and on 4 January 2000, I started work with Dr Chris Smith and the Conflict Security and Development Group at King’s College in the Strand. From that date, developing and expanding the concept of Security Sector Reform (SSR) in countries coming out of conflict became central to my professional life. It was no surprise that there was an anti-military prejudice amongst some of my civilian colleagues within the CSDG who saw SSR as being solely about enhanced governance and putting shackles on the military. However, while I saw enhanced governance as being important, I also felt that reforming the security forces in their entirety; the military, police, intelligence services and justice sector from the inside was just as critical. Fortunately, Chris Smith also saw the potential benefits of a combined outside-to-in and inside-to-out approach and we all got along just fine. In fact, I loved the various debates that we had.

As I was to quickly discover my job was not simply to commute to King’s daily and participate in debates, to give lectures and write papers, I was to be deployed as an SSR advisor, and in the first two years, I spent time in Bosnia, Sri Lanka, advising the Defence Review Committee and in Rwanda advising President Kagame and his principal staff. In all three countries, SSR was as much about building indigenous capacity as it was about reform and enhanced governance at the national level. With time and experience it gradually dawned on me that SSR needed to be elevated beyond a series of tactical capacity building measures in stove-pipes, to a more comprehensive approach that looked horizontally across the entire military, security, intelligence and justice sectors. In Rwanda, I persuaded President Kagame to allow me to conduct my first national threat assessment and national security review. These are stories for later chapters.

On the morning of 11 September 2001, I was summoned urgently from my office in Strand Bridge House, King’s College, to the TV room to watch the unfolding horror of the attacks against the Twin Towers and the Pentagon. These events were to have a profound effect on my professional life and my focus switched to sharpening the weapons of peace in those countries confronting Islamist terrorism.

Sadly, after four years with CSDG, I was considering leaving. I had taken a significant pay cut to join Kings College but was finding it increasingly difficult to pay Ollie’s and Sophie’s school fees. In early 2003, Kings College was in negotiation with Rand Corporation for me to deploy to Baghdad as the deputy International National Security Advisor but when that fell through, Global Risk Strategies, a new dynamic Private Security Company offered me a six-month contract as operations director of the Iraqi Currency Exchange (ICE) programme in Iraq. This was not SSR and took me back to my days as a Special Forces commander, albeit with a much bigger team, but I had hopes that at the end of the six months I would find an SSR related job in Baghdad. The ICE was an amazing challenge that tested me to the full as it involved collecting all of the existing Saddam-headed Iraqi dinars and replacing them with new money printed in the UK. In all, we took receipt of 27 jumbo jets full of new dinars to the value of US$4 billion that we had to deliver to 42 Iraqi banks across the country. This required three trips to each bank to deliver the full amount and to collect the old dinars for destruction. Needless to say, this was a hazardous process and we took a number of casualties.

After this jaunt into the commercial world of private security companies, I was approached by Adam Smith International, a UK development company, and asked to go to the Palestinian West Bank, and to develop an SSR strategy for the Palestinian security forces in order to facilitate the ongoing peace process. This was not a well-managed program as I only had limited access to the Palestinian security forces, however, I did manage to write the required paper in which I proposed using SSR initiatives as confidence building measures and reciprocal steps in the peace process between the Palestinians and Israelis.

Although I was no longer a member of the CSDG, our work on SSR was well known and increasingly in demand and after my short contract in Palestine, NATO asked me to go to Afghanistan to work with the Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit and to help review their SSR efforts there. My partner on this contract was an extremely bright young researcher from Oxford University called Michael Bhatia. We produced, what I would call an extremely prescient paper entitled, Minimal Investments, Minimal Results: The Failure of Security Policy in Afghanistan. Probably as a result of this paper, Michael was offered a follow-on contract in Afghanistan by the US government and I was offered a contract by Her Majesty’s Government. Very sadly, Michael was killed two years later by the Taliban with an Improvised Explosive Device (IED). After a shaky start, I was to spend the next two years on an FCO funded contract in Kabul as the Director of the UK support program to the National Security Advisor based in the Presidential palace. After nearly two years working with my Afghan colleagues, President Karzai was able to present Afghanistan’s first national security policy to the International Community at the Serena Hotel, Kabul 2006. This was far in advance, perhaps too far in advance of western thinking at the time, which had its focus on the Global War on Terror, conflating Al Qaeda and the Taliban and killing them. Sadly, the Afghan national security policy, of which I was the principal author was completely ignored by the international generals in Afghanistan at the time, including our own, General Richards, who ploughed on with their preconceived strategically inept plans. The ignorance and/or arrogance of the international community and their failure to listen and understand the aspirations and plans of the indigenous government of the countries in which they are intervening is a recurring theme in these memoirs.

When I finished my contract in the Palace in Afghanistan in 2006, I continued to work on SSR issues and for several years flip-flopped between working for private security and development companies and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). This has allowed me to make a direct comparison between the two and I’m afraid that the UN comes a very poor second.

My first contract with UNDP was as the UN Disarmament, Disbandment and Reintegration (DDR) advisor tasked with coordinating UN efforts with those of the U.S. forces in the DDR of 103,000 Sunni militia; the Sons of Iraq from the ‘Awakening’ who had forced Al Qaeda out of Anbar Province. This did not start well as within hours of my arrival, the UN compound where I was staying was hit by a large 155 mm rocket that killed a number of UN administrative staff who were living in unprotected accommodation. To win international funding for this contract, UNDP had claimed that they had the support of the other UN agencies in Iraq, however that was not the case and with the refusal of the other agencies to coordinate their efforts and work with the military coalition, the DDR program, much to my and the military’s frustration became an exercise in futility and I flew back to London.

While back in the UK, I was asked by an old friend to do a short consultancy for Aegis Defence Services in London, which turned into a year-long contract. I enjoyed my time with Aegis who were extremely professional and good to their staff. I struggled with the commute from Wiltshire but enjoyed some of my jobs. I enjoyed writing the complete security plan for a new city that was to be built in the sands of Saudi Arabia, to be called the King Abdulla Economic City, and I enjoyed helping update the curriculum of the of the Ghanaian military staff college. On one occasion, I had the privilege of writing a threat assessment with three retired Regimental Sergeant Majors from the SAS, the Royal Marines and Infantry Training School at Brecon. The only down-side of working for Aegis was the founder and CEO, Tim Spicer, who I considered a complete ‘spaceman’. He liked to boast that Aegis did danger, whereas I preferred to say that we did risk management. Fortunately, Spicer rarely appeared in the office!

During this lull from government and UN work, I also had nearly a year working for a US private security company called Transpire Group. M...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Dedication

- Copyright Information ©

- Acknowledgment

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen