- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History of Wales in Twelve Poems

About this book

Down the centuries, poets have provided Wales with a window onto its own distinctive world. This book gives a sense of the view seen through that special window in twelve illustrated poems, each bringing very different periods and aspects of the Welsh past into focus. Together, they give the flavour of a poetic tradition, both ancient and modern, in the Welsh language and in English, that is internationally renowned for its distinction and continuing vibrancy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The History of Wales in Twelve Poems by M. Wynn Thomas,Ruth Jên Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ANEIRIN

Y Gododdin

seventh century

Gwŷr a aeth Gatraeth oedd ffraeth eu llu;

Glasfedd eu hancwyn, a gwenwyn fu.

Trichant trwy beiriant yn catáu –

A gwedi elwch tawelwch fu.

Cyd elwynt lannau i benydu,

Dadl diau angau i eu treiddu …

O freithell Gatraeth pan adroddir,

Maon dychiorant; eu hoed bu hir.

Edyrn diedyrn amgyn’ dir

meibion Godebog, gwerin enwir.

Dyfforthynt lynwysawr gelorawr hir.

Bu tru o dynghedfen, angen gywir,

A dyngwyd i Dudfwlch a Chyfwlch Hir.

Cyd yfem fedd gloyw wrth leu babir,

Cyd fai da ei flas, ei gas bu hir.

Catraeth-bent went a voluble host.

Three hundred packed in close array.

Din of feast; then

Silence.

Due penance done in myriad churches,

Yet stone-deaf death riddled them through …

Tales come from Catraeth tell

How heroes fell, were mourned long.

Fierce land-protectors,

Sons of Godebog, true to the end.

Bodies stretched on blood-soaked biers,

Doomed to face the wretched reckoning

Decreed to Tudfwlch and Cyfwlch Hir.

Glow of wine in candle flame,

Sweet the taste, the aftertaste bitter.

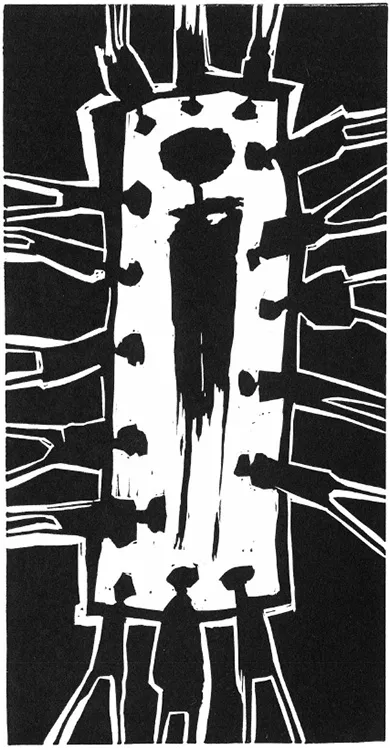

This famous seventh-century work by Aneirin is one of the very earliest poems in Welsh to have survived, and it shows how Welsh poetry began to take distinctive shape. One of its lines in particular has lingered in the collective mind for a millennium and a half: ‘Ac wedi elwch tawelwch fu.’ ‘Elwch’ is ‘feasting’, ‘tawelwch’ is ‘silence’: the raw, brutal juxtaposition of the two simple words sends a shiver down the mind’s spine; while the tie of rhyme makes the fateful link between the two inexorable. Moreover ‘tawelwch’, ‘silence’, is actually composed of ‘taw’ (to put an end to’) and ‘elwch’ (‘feasting’).

Such a memorable composition makes clear the part poetry began to play in the fashioning of a new language – ‘Welsh’ – out of a mixture of the original Celtic tongue and elements from the Latin of the Roman conquerors. The making of this new language was also the making of a new people. In early Welsh the word ‘iaith’ stood both for a language and for the people who spoke it. The tribal poets (‘bards’) played an important role in all these developments and were accordingly granted a highly respected place in the social structure of the day. They were the custodians of tradition, lore and tribal ‘history’, and they sang the praises of the heroes of a warrior society.

Following the withdrawal of most Roman troops with Macsen Wledig (Magnus Maximus, 383 ce), the speakers of this new language were scattered across much of mainland Britain. But they came increasingly under attack from bands of foreign marauders from the Continent. The Catraeth poem tells the story of one such native group’s brave and epic attempt to fend off Germanic invaders at Catraeth (Catterick). It speaks of a tiny warrior band that was feted and feasted for a whole year before being sent to heroic annihilation in battle with a much greater enemy force.

That band actually started out on its futile quest not from Wales but from the lowlands of Scotland. The fate that befell it foreshadows that of many others of the native Britons the length and breadth of the island who tried to defend their territories. The invaders steadily prevailed, driving wedges that left the natives isolated from each other until eventually the remnants of indigenous society were confined to small marginal areas such as modern Cumbria (which comes from the same root as ‘Cymru’) and Cornwall. From there a small group fled further to Brittany, which became known as ‘Little Britain’ to distinguish it from ‘Great Britain’ – in origin the term had nothing to do with a global British Empire. But, of course, above all they retreated to Wales.

There the people came to call their land self-protectively ‘Cymru’, and themselves first ‘Brythoniaid’ (Britons) and then ‘Cymry’ (‘comrades’), although the invaders – mostly of Saxon origin – referred to them dismissively as ‘Welsh’ (a foreign, Romanised people). With the passing of the centuries, their relations with their neighbours took the form not only of sporadic confrontation but of judicious intermarriages, diplomatic alliances and cultural exchanges. Coastal regions were particularly important areas of encounter – sea voyaging was after all much the easiest mode of travel, and made possible significant incursions and extensive settlements from Ireland and also by Viking invaders.

The names of several of the most prominent ‘tribal’ warlords of the period have come down to us through legend (e.g. Gwrtheyrn/Vortigern; Arthur). The names given to some of the more powerful and stable of their often fluid regional societies also remain in present-day vocabulary, as in Dyfed, Gwynedd and Powys. Some of these regional overlords even proved sufficiently powerful to extend their sovereignty over virtually the entire area of the country and could thus reasonably claim to be princes of the whole of Wales, a prominent example being Rhodri Mawr in the ninth century.

These Romano-British peoples who were in the process of becoming collectively known as ‘the Welsh’ had become Christianised before the departure of the Roman legions, and were thereafter to remain bound closely to that religion first through their own holy-men (the ‘Celtic saints’, most famously David) and then by being (reluctantly at first) plugged in, through their monks and clergy, to the Europe-wide system of the Catholic religious establishment. Wales duly developed its own great monastic centres of learning at Llanilltud Fawr (Llantwit Major, where the earliest Celtic saints of Ireland were educated), Llandeilo Fawr and Llanbadarn.

From the manuscripts that were eventually produced there, as later in the Norman monasteries, we glean many of the uncertain ‘facts’ that allow us glimpses of early Welsh ‘history’. Mention is made for instance of Cunedda, a powerful warlord from lowland Scotland, reputed to have established a sixth-century dynasty in Gwynedd, some members of which went on to create their own power bases in areas subsequently named after them – Ceredig(ion), Meirion(nydd), etc. And we also hear of Gwrtheyrn (Vortigern), the ruler credited with the disastrous decision to invite mercenary Saxon bands over from the Continent to bolster-up his power.

As the centuries passed, and a series of ever more powerful and stable regional ‘kingdoms’ rose and fell the far side of the boundary Dyke that had been established, with Welsh co-operation, by Offa king of Mercia, the Welsh peoples responded by variously resisting, adapting and bending the knee to superior power in order carefully to protect what remained to them of ‘independence’ and self-rule. It was a mixed policy that allowed for important cultural exchanges: for instance, the celebrated code of laws constructed in Dyfed (south-west Wales) by Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), a particularly enlightened tenth-century ruler of the large part of Wales, owed much to his connections with Wessex as well as to his familiarity with continental precedents.

ANON.

Pais Dinogad

seventh century

Pais Dinogad, fraith fraith,

O grwyn balaod ban wraith:

Chwid, chwid, chwidogaith,

Gochanwn, gochenyn’ wythgaith.

Pan elai dy dad di i heliaw,

Llath ar ei ysgwydd, llory yn ei law,

Ef gelwi gŵn gogyhwg –

‘Giff gaff; daly, daly, dwg, dwg.’

Ef lleddi bysg yng nghorwg

Mal ban lladd llew llywiwg

Pan elai dy dad di i fynydd,

Dyddygai ef pen iwrch, pen gwythwch, pen hydd,

Pen grugiar fraith o fynydd,

Pen pysg o Raeadr Derwennydd.

O’r sawl yd gyrhaeddai dy dad di â’i gigwain

O wythwch a llewyn a llwynain

Nid angai oll ni fai oradain.

Dinogad’s smock is pied, pied –

Made it out of marten hide.

Whit, whit, whistle along,

Eight slaves with you sing the song.

When your dad went to hunt,

Spear on his shoulder, cudgel in hand,

He called his quick dogs, ‘Giff, you wretch,

Gaff, catch her, catch her, fetch, fetch!’

From a coracle he’d spear

Fish as a lion strikes a deer,

When your dad went to the crag

He brought down roebuck, boar and stag,

Speckled grouse from the mountain tall,

Fish from Derwent waterfall.

Whatever your dad found with his spear,

Boar or wild cat, fox or deer,

Unless it flew, would never get clear.

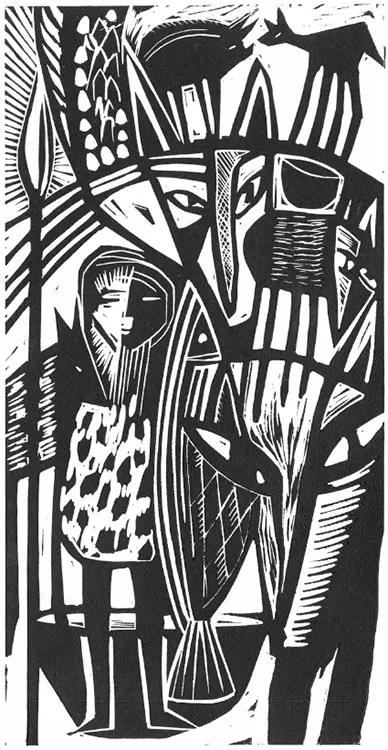

This enchanting lullaby with its tender domestic setting dates back possibly to the seventh century. It delightfully captures a mother (perhaps) ‘bigging up’ her man, the sleeping baby’s father, and it evokes an everyday masculine world of fishing, hunt and chase. It therefore briefly grants us – just like an exquisite miniature in a great medieval Books of Hours – a very rare intimate glimpse into the ordinary life of the time. And in being sung by a woman, this loving cradle song briefly breaks the terrible eternal silence to which the poor anonymous masses of this era have otherwise been condemned by history. This fragment, therefore, brings to our modern attention the plight of this vast population of the unheard – the girls, the women, the babies, the children, the physically and mentally impaired, the old and the infirm; all the callously casual casualties of conflict; and all members of the huge underclass of serf and slave labour upon which a warrior society in reality totally depended for basic sustenance, for all its macho heroics and cult of alpha-male heroes.

A few other poems from this era also allow us parallel glimpses into a mysterious underworld of experience otherwise forbidden to us. There is the remarkable legend of the distracted Myrddin Wyllt, for example. He was driven so mad by the carnage he witnessed at Arfderydd that he took refuge in a dense for...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. Aneirin: Y Gododdin (extract)

- 2. Anon: Pais Dinogad

- 3. Anon: Stafell Gynddylan (from Canu Heledd)

- 4. Gruffudd ab yr ynad coch: Marwnad Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

- 5. Dafydd ap gwilym: Trafferth mewn Tafarn

- 6. Henry vaughan: The World

- 7. Anon.: Hen Benillion

- 8. Ann griffiths (Dolwar Fach): Wele’n sefyll rhwng y myrtwydd

- 9. Gwenallt: Y Meirwon

- 10. Dylan Thomas: Fern Hill

- 11. Gillian Clarke: Blodeuwedd

- 12. Menna Elfyn: Siapauo Gymru