![]()

1

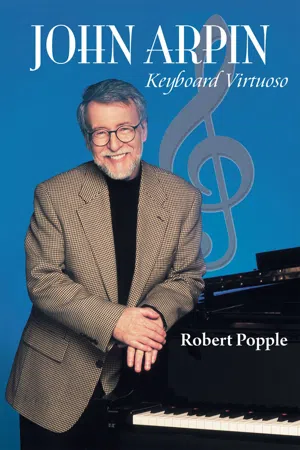

Yamaha's Designated Artist

Tokyo, Japan. December 1982. The renowned Canadian pianist John Arpin, who grew up in Port McNicoll, Ontario, is onstage in the Kan'ihoken Hall before a capacity crowd of seventeen hundred. He is competing in a Yamaha-sponsored, worldwide composer-arranger-performer music festival, billed as the Second International Original Concert. When the competition started several days earlier, more than 450 competitors from thirty-nine countries had converged on Tokyo in pursuit of the coveted gold medal that would signify the best in the world. Preliminary elimination rounds were used to winnow out the top fourteen competitors, each of whom would give a final, audience-judged performance on one of two nights, each night featuring seven competitors.1

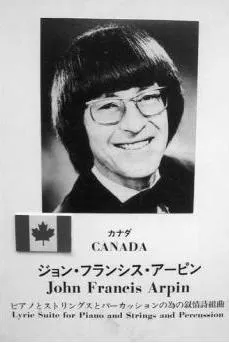

Immersed in music from the age of four, John Arpin is the sole Canadian finalist in this mother of all music festivals. In making his selection of material, Arpin knew that it had to be something melodic, nothing angular or atonal, something that would appeal to the Japanese ear. On this occasion he is coaxing his melodious signature sound from his own composition Lyric Suite for Piano, Strings, and Percussion.2 His fingers barely graze the keys of the Yamaha concert grand, yet each finger lands with astounding accuracy and effect, his unmatched technique the product of millions of note soundings over forty years of hard-won practice and performance. String players supplied by the Japan Philharmonic Symphony provide the accompaniment, together with a drummer on loan from a local swing band, who adds a background bossa-nova beat. Arpin's mop-top hairstyle, popular in the Beatles era and reminiscent of the tennis star Jimmy Connors, perhaps plays to his advantage, reminding some in the audience of the great Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa. Arpin and his ensemble execute the work flawlessly, to thunderous applause.

Some four years earlier the Yamaha Corporation had recruited John Arpin as their Designated Artist in Canada. Consistent with their corporate philosophy of relentlessly pursuing excellence, they had picked the very best. The contractual relationship was to last two more years, harmonious, even synergistic, for most of that time, but would end on a point of principle: whether the Japanese could teach Western music as well as Westerners did. An industrial colossus engaged in the production and marketing of goods ranging from guitars to motorcycles and featuring a "see the quality, feel the quality, hear the quality" approach throughout, Yamaha was moving abroad aggressively with their product line in 1982. Their goal was to usurp market share in all their product areas, with the particular objective of becoming the piano manufacturer of choice in North America, if indeed not the world. Innovations that set them apart from their competition in the quest for acoustical perfection included the use of modern materials such as Teflon in critical areas of the piano's action, whereas competitors were sticking dogmatically to traditional materials. The company's marketing arsenal of proactive initiatives made their competitors appear reactive, change-averse, even reluctant. One such initiative was their global composer-arranger-performer competitions.

On this evening in 1982 the corporation is featuring, of course, their nine-foot grand piano. The instrument is positioned prominently among the many other instruments in the orchestra — most of which, if not all, Yamaha also manufactures — to accompany or be played by the fourteen finalists.

Because the performances will be audience-judged, each member of the audience is equipped with a wireless electronic scorer into which are entered scores on originality, performance level, and enjoyment level.3 A central computer will collate and analyze the results. Arpin has drawn the fifth slot; only two performers will follow him on this night, seven on the following night. Unlike many of his competitors, who hope to impress the audience with their inventiveness by using eclectic combinations of instruments and unconventional chord progressions, Arpin's entry is of an easy-listening variety.

As the competition heats up, one of the finalists, Arnaud Dumond from France senses that he has been outfoxed by the versatile musical prodigy from Port McNicoll. Offstage, Dumond begins to disapprove of Arpin's choice of material. He derides Arpin's submission as being a half century out-of-date. His, on the other hand, his argument goes, is leading-edge, pushes the envelope, "new stuff that's never been done before." Scarcely blinking at this affront to his choice of material, Arpin leaves Dumond poleaxed with his response: "So what? People across the world are still talking about those guys who wrote stuff fifty years ago [in the most creative era of America's musical history] — and it's never been matched. Nobody's even heard of you yet. And by the sound of some of the stuff that you are presenting likely never will." Later the conductor takes Arpin aside and comments sotto voce: "They tell me Dumond is the only one writing such far-out material — and frankly, we're hoping he is the only one."4

This poster-size announcement of John Arpin's participation in Yamaha's 1982 Second International Original Concert hung in Tokyo's Kan'ihoken Hall advertising Canada's sole entry in the competition.

When Dumond's turn comes, he presents a three-part composition entitled Medee-Midi-Desert, described in the program as an "enigma of three mingled moods, beginning with a Greek tragedy that includes an orgy, a second movement depicting a Romanesque midday ghost's hour of mirages and delirium, culminating in a third movement of bareness, loneliness, shrieking, and, ultimately, silence."5

An orgy? Delirium? Bareness? Shrieking? Far-out indeed. Surprisingly, Dumond's performance must have appealed greatly to the audience, because he earns a top mark in the competition. Astoundingly, when the results for originality, performance, and enjoyment are tallied, Arpin and Dumond tie for the gold medal. As a result, an atmosphere of uncertainty descends upon the scene. This is an outcome that no one anticipated. There is no feasible way to break the tie, although if each competitor had been required to give an encore performance as a tiebreaker, Arpin would have undoubtedly risen to the occasion. One wonders whether Dumond came with comparable capabilities, but history will never know the answer.

Having struck only one gold medal, the Yamaha event organizers are thrown into discreet disarray. They cannot award two gold medals on the spot because they have only one. Since both competitors earned gold, however, they could have awarded two golds, with one to follow to the loser of a coin toss, for example. That option may have been considered but was not pursued. Having several silver medals on hand, however, they decide to award the top two finishers, Arpin and Dumond, silver medals — an option that really did not match the competition outcome, since Arpin and Dumond tied for first.6

Sensitive to the criticism of overpromoting a single-company-sponsored event, the Canadian media provide minimal coverage of Arpin's achievement, presumably believing that there is something wrong with such an event. But what? How much more impartially can a competition be judged than by each person in the audience inputting scores into a computer against pre-selected criteria? There was nothing to prevent a Canadian piano manufacturer from hosting a similar event in Canada. And if one had, one can only assume that the same rationale would have prevented the event from being properly covered by the media. Almost grudgingly, Canadian newspapers report the Japan event in a few brief sentences on one of their inner pages as if it is an everyday, unimportant occurrence, stating, somewhat inaccurately, that Arpin won the competition. The facts of the tie go unreported.7

How typically Canadian. Is it any wonder that we have so few heroes? Had that been an Olympic medal — silver or otherwise — its recipient would have been pictured on the front page of every newspaper across the country, accompanied by glowing columns of print. But in a very real sense, the Japan event was an Olympics — of music. It was a global competition for which the rules of engagement required the competing musicians to compose, arrange, and perform an original suite of music. Certainly, Yamaha's 1982 worldwide competition was not an everyday event and warranted more Canadian media stature than it received — particularly in view of the result. It is another startling example of how the achievements of our brightest, our best, our highest achievers, oftentimes are underappreciated, and sometimes even unnoticed.

The Camera

On arrival in Tokyo, Arpin had been assigned the affable Miki Yoshimori to act as his guide and interpreter for the duration of the visit.8 They were to become lifelong friends.

Soon after the competition, they boarded a bullet train down to Hamamatsu, site of the Yamaha piano production plant, for a tour. However, as soon as they got off the train and it had departed the station as soundlessly as it had arrived, Arpin realized that he had forgotten his newly purchased Japanese camera, a top-of-the-line Konika, which he had left sitting on his seat of the now rapidly receding train.

As Arpin's eyes frantically darted across his baggage and he felt for the neck strap upon which the camera had been dangling, Miki sensed that something was wrong.

"You forget something?" inquired his interpreter.

"Yeah, my camera. I forgot my new camera on the train," replied Arpin.

"Too bad! I not worry much!" said Miki.

Marching smartly over to a manned kiosk, Miki engaged the attendant in some Japanese dialogue sprinkled with broken English, within which Arpin could decipher only "… fliend … Canada …" and "He forgot camela on seat."

In response to the attendant's question in Japanese, Miki turned and queried Arpin, "You have ticket?" Arpin handed over his ticket stub. After pulling down a giant roller blind, which was a seat-by-seat layout of the train, the attendant pinpointed the seat Arpin had been sitting in and confirmed his selection with Miki.

Following the exchange of a few more remarks in Japanese, Miki turned to Arpin and said, "We go to hotel now."

"What about the camera?" asked an apprehensive Arpin.

"We wait. This man call," replied Miki.

As the two were checking into the hotel, Miki instructed the desk clerk in his snipped English, "We waiting call from railway. We in lestaulant. You get call. You call me. Miki Yoshimori. Please don't forget!"

Some minutes later there was a page in the restaurant for Miki. He promptly reassured Arpin, "Maybe railway call. Back in two minutes." He exited to respond to the page, only to return a minute or so later sporting an ear-to-ear grin.

"Ahhhhh! They find camela. You know why I not worry? Somebody touch that camela not belong to them, they go to jail. Family disown!"

The camera was soon back in Arpin's hands.

Hamamatsu

The visit to the Hamamatsu floored the gifted pianist. He saw one of the most impressive manufacturing plants of the post–Second World War Japanese economic revival. The assembly line had the footprint of eleven football fields9 arranged in a production cluster. Arpin watched the line grind relentlessly on with Swiss-watch precision as each sub-assembly procedure dovetailed with the master train and each component was painstakingly and lovingly put in place at each stopping station. The pride of workmanship injected into each and every piano was remarkable to see.10

The woods used, vital to producing consistency of sound in the final product, were handled with the utmost of care in a series of rooms adjoining as many as four main assembly lines. The woods and the partially assembled pianos were stored in separate climate-controlled rooms, each storage room with its temperature and humidity replicating the climate of the piano's destination country. (One wonders which Canadian location was picked as representative of Canada.) The climate control even included time-of-day characteristics, peaking in humidity or temperature midday, as Yamaha research had shown to be the case. This remarkable collection of one-room micro-climates covered all the main destinations around the world. If the piano was going to Southern California, it was stored in the Southern California room. It would be removed for just-in-time arrival at the next work station of its assembly, the required assembly would be executed, then the piano would be returned promptly to the Southern California storage room, all on giant conveyor belts. If a piano was going to Great Britain, the same principles and procedures applied, and so on. Each piano had a "home room" in which it lived until it was packed, sealed, and crated for shipment to its destination.11

Every morning at about ten-thirty, a loud whistle would sound, the conveyors would stop, and each worker would run to a predetermined area for a ten-minute calisthenics break, with all the workers falling into line in precisely sized groups. An instructor would lead each group as it exercised in lockstep, a picture of military precision. Another whistle blast signalled the end of the exercise period, whereupon all the workers ran back to their assembly-line stations and resumed their work. A similar exercise break occurred in mid-afternoon. As John noted, "The idea was to prevent their muscles from becoming too relaxed. And every one of those workers lived in a house built and owned by Yamaha. As long as they worked for Yamaha, the house was theirs, for use by themselves and their family, free of charge."

Following the trip to the Yamaha piano factory, Miki took Arpin down to Kyoto, where his sister-in-law, who was married to a doctor, lived with her family. Miki also introduced John to another of his sisters-in-law, this time a beautiful young Japanese girl n...