![]()

1

Wedding at Westminster

“A flash of colour on the hard road”

— Sir Winston Churchill

By the time the Second World War came to an end — with the surrender of Japan to the Allies on August 14, 1945 — Britain had been at war for just under six years. While the entire British Commonwealth and Empire and its allies rejoiced at the defeat of the Third Reich and the evil it embodied, life in Britain did not immediately return to pre-war normality. Instead, severe rationing remained in effect. While no one would wish for the conflict to resume, everyday life was full of hardships and deprivations and many Britons endured lives still echoing the dreariness of wartime but with none of the drama.

A welcome distraction from this seemingly endless postwar austerity was provided by the Royal Family when, on July 9, 1947, the announcement came from Buckingham Palace heralding the engagement of Her Royal Highness The Princess Elizabeth to Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, RN. The wedding — on November 20 of that same year — was described by wartime Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill as “a flash of colour on the hard road we have to travel.”

At ages twenty-six and twenty-one respectively, Philip and Elizabeth were the Charles and Diana of their era on their wedding day, according to their cousin, the Countess Mountbatten of Burma. Recalling the excitement surrounding the royal wedding sixty years later, the Countess said, “If you think in terms of the Prince of Wales and Diana, it was exactly the same. I mean, they were the sorts of star personalities and it was the first time television was being used and they were, absolutely, stars. And everybody was very happy … for the Princess to find such a nice husband. Everybody was rejoicing.”

Clement Attlee’s Labour Government did not declare November 20, 1947, a national holiday, but this refusal did not prevent thousands from camping out on the streets of London in an effort to secure a view of the wedding procession and millions more around the world from listening to the ceremony on the wireless and devouring wedding coverage featured in newspapers, magazines, and newsreels. A fortunate few were able to watch the ceremony on television. By mid-October — nearly a month before the wedding — one spectator seat along the route had sold for £3,000, while one room in Whitehall had been rented for nearly £4,000.

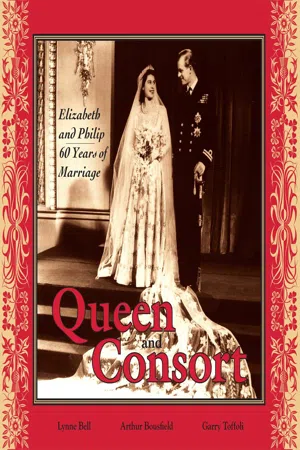

Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh exchange loving looks while posing for their wedding photograph. The wedding was “a flash of colour” in the postwar years.

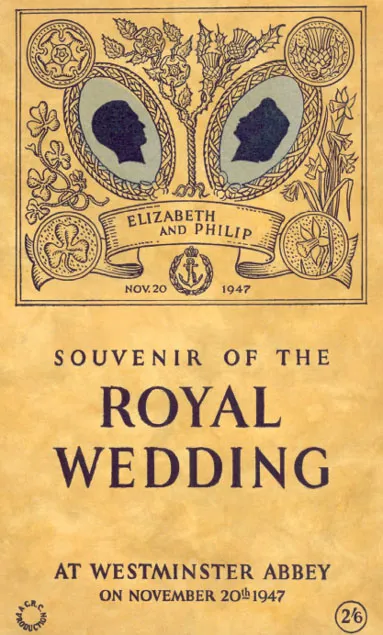

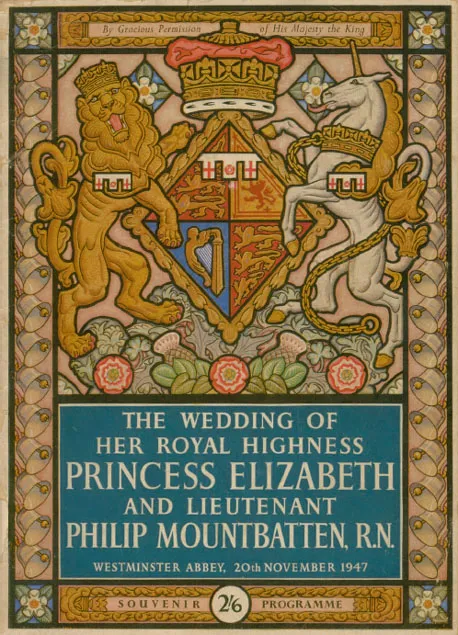

Documents recently released by the National Archives in London demonstrate both the enthusiasm of ordinary people for the wedding and the concerns of the Palace and branches of government regarding the production of wedding souvenirs. While Palace courtiers seemed to be most worried about poor taste, the government was uneasy about the impact on Britain’s weakened industrial base of producing impractical trinkets, such as flags and handkerchiefs bearing likenesses of the royal couple. However, public demand prevailed and royal wedding mementos were produced, to the delight of the majority of the British public. Although central London would not be floodlit, the Princess’s trousseau would be less lavish than that of her mother, and fewer banners would be hung farther apart on lampposts along the wedding route, the wedding was still an impressive example of royal pageantry at its best. The public was treated to a spectacle worthy of a fairy tale and the stage was set for the Princess’s life as a beloved — and very visible — future monarch.

Not since the funeral of King Edward VII in 1910 had so many members of royal houses near and far converged on London. Although rationing was still in effect, foreign royals threw off the shackles of wartime austerity, and the finest suites in London’s finest hotels were soon filled with crowned heads and their royal retinues. The guest list included the King and Queen of Denmark; the King and Queen of Yugoslavia; the Kings of Iraq, Norway, and Romania; the Queen Mother of Romania; the Queen of the Hellenes; the Belgian Prince Regent; Princess Juliana, the Regent of the Netherlands, and her consort, Prince Bernhardt; the grand ducal family of Luxembourg; the deposed royal family of Spain; and Queen Salote of Tonga.

A cake stand depicting the royal couple was one example of the less expensive wedding commemoratives.

Philip’s sisters — married to Germans — were not invited to the ceremony but sent him a gold pen engraved with their names as a wedding gift. His devoutly religious mother, Princess Alice of Greece, set aside her nun’s habit and wimple and donned a lace gown and matching hat in honour of the occasion. In spite of the outlaw status of her daughters and their spouses, Princess Alice had earned her place in Westminster Abbey, and not merely as the groom’s mother. Rather, she had demonstrated goodness and courage during the war, as she had hidden a Jewish family in her Athens home during the German occupation of Greece. Years after her death, her son accepted a posthumous award for her valour from the state of Israel. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, formerly King Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson, who shared a reputation of self-interest during the Second World War, were also left off the invitation list. They spent the wedding day in America.

The bride’s day began with a cup of tea brought to her by her faithful and formidable dresser, Miss Margaret “Bobo” MacDonald. According to the ever-present Marion “Crawfie” Crawford, the bride’s former governess, Princess Elizabeth, in her dressing gown, peeped excitedly out her windows at the crowds who had camped out in the bitterly cold weather, fifty people deep in some places.

A beautiful Princess Elizabeth poses in her magnificent wedding dress.

According to Crawfie’s account, the excited bride-to-be told her, “I can’t believe it’s really happening. I have to keep pinching myself.”

The bride’s dress had been personally delivered the night before by its creator, Norman (later Sir Norman) Hartnell. Hartnell had been responsible for the romantic wardrobe adopted by Princess Elizabeth’s mother, Queen Elizabeth, when King George VI ascended to the Throne. One of the dresses, famously worn by her in a photographic portrait by Cecil Beaton, is both romantic and regal, a feat he was to repeat with this, the wedding dress of a future queen. Although rationing was still in effect, the Princess was allotted one hundred extra clothing coupons towards the creation of her wedding gown, and so the dress did not visibly reflect any postwar dreariness. The secrecy surrounding its creation made its eventual unveiling even more exciting. Workers at Hartnell’s studio all signed confidentiality agreements and workroom windows were whitewashed and covered with thick white muslin to further ensure privacy.

The dress — inspired by Botticelli’s painting Primavera — was made of ivory satin and tulle and embroidered with more than ten thousand seed pearls patterned as white roses of York entwined with ears of corn embroidered in crystal. The dress and train also featured other embroidered flower motifs: syringa, jasmine, and wheat ears among them. The dress took two months of work by twenty-five needlewomen and ten embroiderers to complete. The Princess’s shoes were matching peep-toed satin slingbacks with high heels by royal shoemaker Edward Rayne. The eight bridesmaids — led by Princess Margaret and including Princess Alexandra of Kent and Lord Mountbatten’s daughter, Lady Pamela Mountbatten — were also dressed by Hartnell. Cleverly, each of these dresses featured a large satin bow at the bodice, but the gowns were constructed largely of unrationed net material and embroidered with tiny stars. Even so, the bridesmaids also used all of their clothing rations for these very special dresses. The fabulous Russian tiara given to her by her grandmother, Queen Mary, anchored the Princess’s tulle veil. Often worn by Queen Elizabeth II throughout her reign, this tiara features a series of graduated spikes, each of which is composed of diamonds arranged by size.

The tiara was featured in one of the lastminute glitches that seem to plague most weddings, from the humble to the grand. The wedding of Elizabeth and Philip was not immune. As the tiara was being placed on the Princess’s head (her hair having been styled earlier by the prominent hairdresser Monsieur Henri) during the seventy-five-minute final fitting, it snapped in two. The tiara was soon repaired, but then it was found that the Princess’s double-strand pearl necklace — a wedding gift from her parents — was not in her dressing room at Buckingham Palace but rather at St. James’s Palace displayed with the couple’s other wedding gifts. Elizabeth’s recently appointed private secretary, Jock Colville, came to the rescue and retrieved the pearls in time, but only after commandeering and then jettisoning the car carrying King Haakon VII of Norway and embarking on a harrowing journey by foot through the crowds gathered around both palaces! The bride’s bouquet had gone missing as well. Fortunately, a full search of Buckingham Palace was cut short when a helpful footman revealed he had put the flowers in an icebox in an effort to properly preserve them.

Although the Princess glittered in her wedding finery, she was, of course, unable to wear all of the jewels she had received as wedding gifts. Her parents had also given her a sapphire and diamond suite of necklace and earrings and a pair of Cartier diamond chandelier earrings, among other jewellery. Coincidentally, the geometric style of the earrings was reminiscent of Philip’s wedding gift to his bride — a diamond bracelet he had designed himself. Philip had also designed the couple’s gifts to their bridesmaids — tiny gold compacts with the initials “E&P” traced in jewels. Queen Mary gave her granddaughter not only the Russian tiara but also more spectacular and sentimental pieces of jewellery, including an antique diamond stomacher, Indian bangle brooches studded with diamonds and meant for an empress, and the ruby earrings King George V had given her for her fifty-ninth birthday. Other gifts of jewellery included rubies from the people of Burma, a 54.5-carat uncut pink diamond from the Canadian tycoon John T. Williamson, a diamond tiara and bandeau from the Nizam of Hyderabad, and an emerald and diamond necklace from the people of Victoria, British Columbia. With diamonds from his mother’s tiara, Philip gave his bride a brooch in the shape of a Royal Navy badge.

A diamond and ruby necklace was one of the wedding gifts given to Princess Elizabeth by her parents, the King and Queen.

The Canadian gift for the Duke of Edinburgh was wood panelling in white Canadian maple for his study at Clarence House.

The nearly three thousand wedding gifts the couple received included a racehorse, a twenty-two-carat gold coffee service, a hunting lodge in Kenya, and a television set. From Canada, Elizabeth received a mink coat and the couple received maple furniture for their country home and wall panelling for Philip’s study in Clarence House. The newlyweds received a striking Chinese dinner service — featuring orange dragons — from President Chiang Kai Shek, a Steuben crystal bowl engraved with a merry-go-round from Presi...