1

The Ruins on the Shore

There are ruins in Saint Peters: a small fortress on the shore that is now believed to have been left behind by a seventeenth-century French settlement, and another slightly larger fortress on the hillside overlooking Saint Peters Bay that historians now claim was built by a small English garrison in the late eighteenth century. During my research into the history of Cape Breton Island, I had originally accepted the explanations for these early ruins and so had very little interest in documents relating to the history of the Saint Peters area. I felt that the ruins could have nothing to do with pre-Colombian settlement of Cape Breton.

My interest in Saint Peters grew when I began looking at the history of Cheticamp, the Acadian village on the west coast of the island. Early on in my research I found a shipwreck narrative from 1823 about a small group of sailors, led by a man named Samuel Burrows, that described in great detail how these sailors were rescued and cared for by the local villagers. Some of my ancestors were mentioned. Any story of great bravery in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds is captivating, and these various accounts of young sailors fighting for their lives, having their frozen feet and hands cut off with primitive tools, and then being nursed back to health in Acadian homes, were so fascinating that I looked for other shipwreck narratives from this region. That is when I found the Prenties account from 1780. Initially it was how the lost sailors were rescued by the Mi’kmaq that made the story so appealing, but Prenties’s mention of large French warships sailing across the isthmus of Saint Peters had a certain shock value. His casual observation that the French “had formed a design of cutting through this narrow neck of land, and opening a communication between the ocean and the lake” stayed with me. My curiosity regarding Prenties’s apparent canal forced me to go digging through the historical documents in search of what we actually know of this canal and of these two old ruined fortresses. First, I looked at the ruins.

The one set of ruins that appears most conspicuously through the centuries is a flat earth platform with wide earth walls, located in a cleared area near the shore of Saint Peters Bay. It is just west of the modern, nineteenth-century canal. This canal cuts across the narrow isthmus from Saint Peters Bay to the Bras d’Or Lakes, just as the earlier canal in Prenties’s narrative had. I remembered the ruined fort from when I was a boy growing up in Cape Breton; the ruins were well known on the island. They still are.

These ruins on the shore on the western side of the isthmus were first recorded and mapped by the French surveyors and cartographers who visited the island in 1713. Although these French reports gave the first concrete descriptions of the ruined structure on the shore, the ruins had been mentioned twice before, by two French companies that had tried to establish fishing and trading businesses in Saint Peters during the seventeenth century. The first mention came in 1640, almost seventy-five years before the French military arrived. It is a note in the records of a trading company based in Paris, the Compagnie de Cap-Breton. The company was established in 1633 by Pierre Desportes, a Paris merchant, with the hope of building a fur trading post in Saint Peters.[1] In one document left by the company, dated March 1640, mention is made of Le Fort St. Pierre, the Fort of Saint Peters, for the first time. The captain of a ship contracted by the Compagnie de Cap-Breton was told that when he arrived at Cape Breton he was to follow the orders of the commander stationed at Fort Saint Peters, to “suivre les orders de Louis Parguier, commandant pour Desportes au fort Saint-Pierre” (to follow the orders of Louis Parguier, Desportes’s commander at Fort Saint Peter).[2]

In the mid-seventeenth century, among the reports of early settlements in the Americas, the term fort sometimes simply meant a settlement, what the French also called a habitation. The two terms fort and habitation were sometimes used interchangeably. This first mention of the Fort Saint Peters could simply have meant the settlement of Saint Peters. Perhaps the building — the fort — had not existed yet. Perhaps this fort was just a collection of houses. However, in the case of the documents of the Compagnie de Cap-Breton, the two descriptions also appeared together, the fort and the habitation, “le fort et habitation de Saint-Pierre.”[3] It appears that this company regarded the fort and the habitation as two different things. Fort Saint-Pierre appears to reference an actual structure of some sort that existed apart from the habitation. The settlement — the location of the living quarters — was considered a separate entity.

With no earlier mention of matters relating to the construction of a fort in Saint Peters, it seems to have appeared in the French records already made. It appeared as if the fort was already part of the landscape when the French first began arriving in the mid-seventeenth century.

It is unlikely that the Compagnie de Cap-Breton built the fort. According to the company’s records, it was a very small enterprise. In 1641 the company contracted a nail maker and a single carpenter to work in Saint Peters. They had a two-person workforce, too little to have left anything of substance, and they were forced out of Saint Peters by 1647. Would they have built what the French military would later describe and draw on their maps as a solid earth platform, earthen walls, and a trench or moat, all surrounded by an extensive area of cleared land? The Compagnie de Cap-Breton may have used what was there, but logic suggests they did not build it.

The next time this structure on the shore was mentioned, seventeen years later in 1657, was in a letter from Nicolas Denys, a French fisherman and fur trader who had lived on and off in Saint Peters since 1650. Writing to one of his business partners back in France, Denys complained about the way the fort had been laid out. He claimed that the fort, having been partially ruined by a competitor of his, needed to be rebuilt. More important, he also complained that it was necessary to have a new entrance to the fort at Saint Peters made because he felt the original entrance was in the wrong place.[4] He gave no other explanation other than the original entrance was “très mal place” (very badly placed). The later French surveys show the single entrance centred on the southeast wall. It is not clear from Denys’s letter where he wanted it moved. The important thing about this brief note about a misplaced entrance is that it seems inconceivable Denys would have built something this significant, complete with extensive cleared land, earth walls and a moat, and then wanted it changed. Would Denys have misplaced the door if he had built this fort? His complaint makes it doubtful that Denys was the original builder.

Like the earlier Compagnie de Cap-Breton, Denys appears to have used this strange little fort near the shore on the west side of the isthmus for the location of his business — his trading post. He built a few simple wooden buildings within the walls of the fort for storage and offices that were eventually abandoned after a fire destroyed his business in the winter of 1668–69.

More important for our understanding of the history of Saint Peters, Denys actually claimed to have built the main fort for his settlement — and in this case he used the term fort in his description — in another location.[5] So that there would be no doubt to his claim, Denys also drew a map of Saint Peters Bay and located his flag exactly where he said this main fort was, east of the small fortress on the shore that he had used as a trading post before the fire and east of what is now the modern canal, on a point of land referred to locally as Jerome Point. Denys’s written description matches his map, so there is no reason to doubt him.

The location of Denys’s settlement — the new fort that Denys claimed he built where his settlers lived — has been substantiated by those who came after him. A 1752 census done of the island, Tour of Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque, refers to this tip of land to the east of the harbour as the “Pointe de l’ancienne Intendance”[6] (Point of the Old Intendant). The term ancienne Indendance could only refer to the Denys settlement. In 1653, Denys had been appointed Governor of the region, including Cape Breton Island, after he had purchased it from the Company of New France. He was the Old Intendant. The same term and the same location was used in a series of letters written during the same period by Thomas Pichon, a secretary stationed in Louisbourg who would later become known as “the Spy of Beausejour.” Jerome Point was referred to as “the point of the old intendance.”[7]

It could be that Denys, while claiming to have built the fort for his settlement to the east of the isthmus, at the base of the mountain, actually built a second fort with its flat platform, earth walls, and surrounding moat on the other side of the bay, near the shore on the west side of the isthmus. Logically however, the fort and the settlement would be built as a single unit, the settlers either living inside the fort or in very close proximity. Where safety was an issue, in the wilderness, it would have seemed highly unlikely, even foolhardy, to separate the fortress on the west side of the isthmus and the settlement to the east of the isthmus on Jerome Point. Moreover, why would he build two forts? It appears that the small fort on the shore west of the modern canal already existed before Denys arrived. It was too small for his settlement, so he used it simply as a trading post.

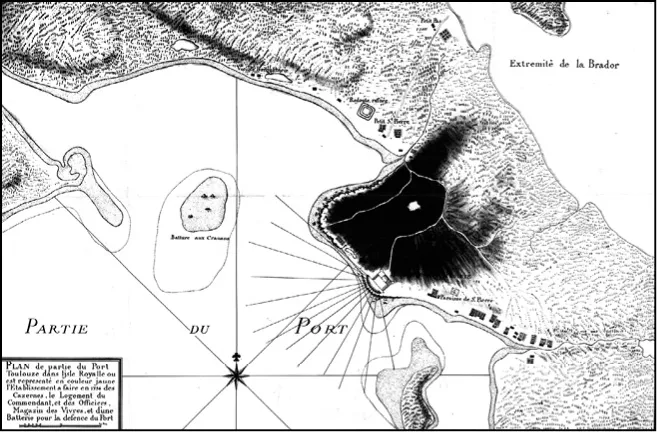

A French map (ca. 1730) of Saint Peters showing the ruins on the shore.

“PLAN de partie du Port Toulouze dans ljsle Royalle ou est representé en couleur jaune l’Etablissement a faire en 1734 des Cazernes, le Logement du Commendant et des Officiers, Magazin des Vivres, et d’une Batterie pour la defence du Port.” Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No. 4125764, NMC34354.

Detail showing the ruined structure on the shore marked as the Redoubt ruinée.

“PLAN de partie du Port Toulouze dans ljsle Royalle ou est representé en couleur jaune l’Etablissement a faire en 1734 des Cazernes, le Logement du Commendant et des Officiers, Magazin des Vivres, et d’une Batterie pour la defence du Port.” Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No. 4125764, NMC34354.

These ruins on the shore to the west of the modern canal were recorded by the French military when they mapped and recorded the geography of Saint Peters beginning in 1713. The structure on the shore on the west side of the isthmus was labelled by the French as a “Redoubte ruinee,” a ruined redoubt, or a small ruined fortress.

Surveyors reported that they had found a square structure, twelve toise on each side. An early French toise equaled just over two metres, so the ruined fortress, when first officially surveyed by the French in the early eighteenth century, was a simple square structure about twenty-five metres per side. According to this survey, it was surrounded by a trench — a moat. The surveyors appear to claim that the walls were made of earth. Much more recent archaeology of the fort claims the walls were built of sod or horizontal layers of soil. The French report mentioned two openings, although the cartographers only showed a single opening in the southeast wall. The actual description reads, “... un fort quarré Revestu de Gazon avec un faussée qui en fait Lanceinte. chague coste peut avoir douze Toises en face. Le faussé a deux ouvertures et un Glacit d’Environ...