![]()

1

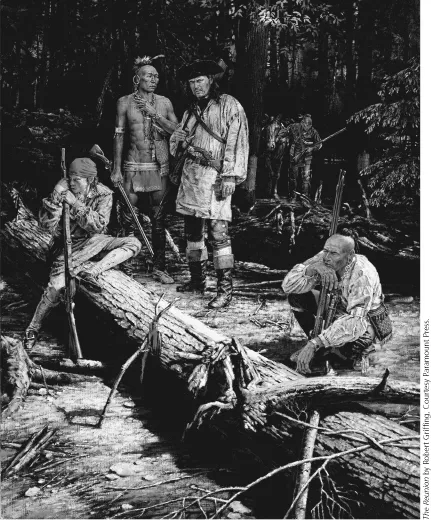

DEADLY ENCOUNTER AT WOOD CREEK,

8 AUGUST 1758

Bernd Horn

Tha-boom! The musket shot reverberated through the Adirondack wilderness shattering the morning stillness. Within seconds two more shots rang out and echoed through the forest.1 Captain Joseph Marin, the veteran French Canadian partisan leader froze immediately. The enemy was close - very close. He quickly, but quietly, arranged his war party of 500 Canadians, coureur de bois, and Natives into a crescent shaped ambush on the edge of the forest clearing. Within minutes the large force virtually vanished as it melted into the thick brush and awaited its unsuspecting prey.

Joseph Marin de la Malgue was well versed in la petite guerre - the savage guerrilla warfare that centered on the use of shock action and surprise to achieve limited objectives.2 Daring raids and ambushes were the preferred methods of the French and their Native allies. They had used them to good effect terrorizing the New England frontiers and tying down large number of provincial soldiers in a desperate attempt to provide security.

Marin was no stranger to the English, particularly Rogers's Rangers. They had played a deadly game of cat and mouse for years - Marin usually the victor. He was once again leading a war party against the British hoping to further demoralize the English by striking them at Fort Edward and Albany. They were emboldened by the French victory at Fort Ticonderoga a month earlier, on 8 July 1758, when Major-General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm's force of 3,600 turned away Major-General James Abercromby's army of 15,000. Although no immediate follow-up was taken by Montcalm at the time, the arrival of more Canadians and their Native allies allowed the French to mount an active raiding campaign to keep the English off balance.

For most of the war, the French owned the forests and their skilled Canadians and Native raiders bottled up garrisons and terrorized settlements tying down large forces in a defensive role.3 Just days earlier on 28 July, another French Canadian, La Corne, with 300 Canadians and Natives massacred a convoy of 116 men and women between Fort Edward and Halfway Brook. Upon hearing of the outrage, Major-General Abercromby immediately ordered Major Robert Rogers4 and Major Israel Putnam, with a combined force of 1,400 men, to run down the impertinent La Corne. Despite their haste they reached the narrow of Lake Champlain too late. La Corne just narrowly missed their noose. However, the stage was now set for yet another encounter between Marin and Rogers.

Rogers's Rangers were created to provide the British with a scouting/ reconnaissance capability similar to the French. However, they never achieved the same level of expertise or success.

Three days later, 11 Rangers patrolling the Wood Creek approach from Fort Ticonderoga stumbled upon fresh tracks of a large Native war party. They pursued the trail for four miles where they decided to halt for a meal. Suddenly, the tables were turned - the hunter became the prey. They were surrounded and attacked by 50 Natives. In the desperate and savage struggle eight Rangers and 17 Natives were killed and two Rangers were captured. Only one Ranger, Sergeant Hackett escaped. Ominously, on his flight to Fort Edward, he discovered additional fresh tracks of an even larger enemy war party apparently heading in the direction of Fort Edward and Albany.

Upon receiving the latest report Abercromby devised a plan to intercept and destroy the unidentified French raiding party. He sent a dispatch to Rogers and Putnam, who were still in the field, to take 700 chosen men and 10 days of provisions and "sweep all that back country" of South Bay and Wood Creek to Fort Edward.

On the night of 31 July, Rogers and Putnam and their force camped on Sloop Island. The next day was spent preparing the expedition and on 2 August, the two men set off with separate groups to set ambushes at the junction of Wood Creek and East Bay and South Bay, respectively. This proved to be unproductive. Four days later Rogers and Putnam rejoined forces and marched to the decaying ruins of Fort St. Anne where they camped on the night of 7 August 1758.

Rogers's Rangers achieved notoriety in the English press. During the initial years, the Rangers seemed to be the only body of troops conducting successful operations against the enemy. Major Robert Rogers was adept at providing colourful exploits to raise the morale of the terrorized population along the frontier.

Little had been accomplished to date. Other than the near capture of an enemy canoe with six warriors there was no sign of enemy forces.5 Vigilance began to slip. Already 170 soldiers were released and they returned to Fort Edward. Rogers's command now numbered approximately 530 as they settled in for the night.

As the sun began to rise over the hills, Rogers and Putnam prepared for the westward march to Fort Edward. Inexplicably Rogers, the author of the famous "Standing Orders of Rogers Rangers," which articulated rules on light infantry warfare in North America, demonstrated a lethal lapse of judgment. A friendly argument fuelled by strong egos developed between Rogers and Ensign William Irwin of Gage's Light Infantry Regiment in regard to who was the more skilled marksman. Words soon led to action and then a series of what would prove to be fatal shots rang out as they fired at marks to prove who was the better shot.6

As the thunderclaps echoed through the forests, not too far away, Marin's reaction was instantaneous. His trained eye surveyed the ground and he quickly spotted an ideal ambush site. Equally swift, he developed a plan and deployed his forces. Between him and the unknown hostile force lay a clearing that was choked with alder and brush. It was dissected by a single narrow trail that led directly into the forest where Marin had positioned his men. The dense cover would allow the enemy to unwittingly walk right into Marin's ambush location, the jaws of death, without knowing it. By the time they realized the threat - it would be too late.

Major Putnam led the column with his 300 Connecticut Provincials in the van. Behind him followed Captain James Dalyell with detachments from the 80th and 44th Regiments. Rogers brought up the rear with his Rangers and the remaining Provincials. Putnam marched right into the ambush. Lieutenant Tracy and three soldiers were suddenly overwhelmed and dragged into the thick brush. Then the French Canadians and their Native allies unleashed a lethal volley on the unsuspecting English troops caught in the open clearing. "The enemy rose as a cloud and fired upon us," recorded one participant, "the tomahawks and bullets flying around my ears like hailstones."7

Putnam immediately ordered his men to return fire and a deadly melee began in the thick alder brush and forest. But the odds were against them. "The enemy discovering them," recounted Dr. Caleb Rea, "ambushed'm in form of a Semi Circle which gave the Enemy a great advantage of our men."8 The Provincial troops quickly broke and fell back behind the Regulars who were led forward by Captain Dalyell.

The battle now centred around a huge fallen tree. Marin pounded the British with four volleys of fire before the "Red Coats" managed to flank the tree and engage the enemy in hand-to-hand combat. At this point, the momentum of the battle began to turn in favour of the British. Major Rogers was at the back of the column with his men. He quickly moved his forces to the sound of battle. The antagonists were now evenly matched and the action raged on for another hour.

The thick bush and alder at the edge of the forest turned the battle into a series of very personal fights as the close terrain prevented much group action. At one point, a monstrous Native chief who stood six feet, four inches tall, jumped upon the large fallen tree and killed two British Regulars who tried to oppose him. A British officer attempting to come to the aid of the stricken soldiers struck the giant with his musket to no avail. Although drawing blood, he only enraged the Native who was about to dispatch the officer with his tomahawk when Major Rogers proved his marksmanship and shot the Native chief dead.

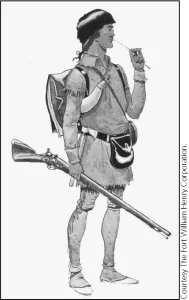

The provincial militia.

Marin now tried to outflank the British, by turning their right flank. He made four valiant attempts, however, Rogers and his Rangers were obstinate and gave no ground. As the inferno raged around him, Rogers sensed the flow of battle and reversed the initiative. He now began to shift his Rangers right in a bid to outmanoeuvre the French Canadians. Some Canadians began to break. Then, the Rangers charged. Half the Rangers would fire, while the other half would reload - in this manner they kept up a constant fire and movement forward. Under this constant fire and pressure the remainder of the French Canadians gave way.

However, Marin was no novice in bush warfare. Realizing the situation he avoided a rout and destruction of his force by dividing the survivors into small parties and taking different withdrawal routes. The groups reunited later that night and made their bivouac in a secluded location surrounded by impenetrable swamp.

The British chose not to pursue. Rather they stayed on the battlefield and buried their dead. As always, the casualty figures vary. However, it appears that British losses added up to 53 killed, 50 wounded and four taken prisoner. The French suffered approximately 77 killed.9

Although, Rogers was partly responsible for creating the ambush because of his careless discharge of firearms, he received credit for driving the French Canadians away. One veteran believed that Rogers displayed "heroic good conduct" and that he "surrounded the enemy and obliged them to quit the field with the loss of their chief and 200 men killed and missing, 80 left upon the field and three prisoners."10 Dr. Rea's account was similar in its praise of Rogers. "As soon as the Enemy perceived Rogers Party flanking upon'm," Rea explained, "they [French and Natives] retreated carrying off their dead and wounded what they cou'd, our men pursued them not but took care of their Dead & wounded & came off so that it seems rather a Drawn Battle than either party victorious."11 Captain Dalyell later informed Major-General Abercromby that Rogers "acted the whole time with great calmness and officer like."12 The accolades continued as Abercromby reported back to British Prime Minister Pitt that "Rogers deserved much to be commended," thus, increasing the fame of Rogers and his Rangers in Europe.13

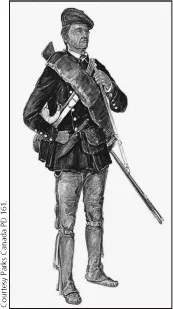

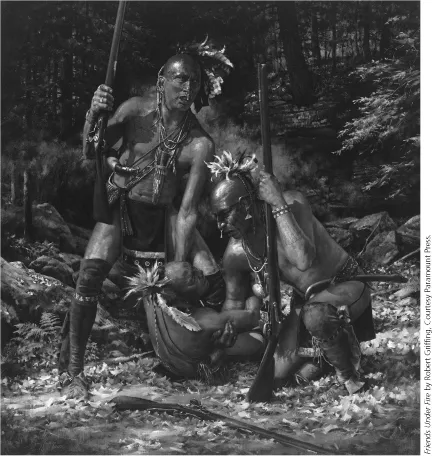

A French Canadian officer discusses the next course of action with his Native ally.

Once the dead were buried, Rogers and his party continued their march for Fort Edwards carrying their wounded on litters made of strong branches with blankets strung over them. En route, a relief force of 400 soldiers under Major Munster, which included an additional 40 Rangers, as well as a surgeon, met the column. Rogers then encamped for the night.

Although Rogers and his surviving force revelled in what they considered a victory that night, the encounter still proved potentially deadly for Major Putnam. After discharging his musket several times, his close proximity at the head of the column put him in a desperate position. Unable to reload, without support and confronted by the enemy, Putnam surrendered. He was unceremoniously tied to a tree, while his captors fought the remainder of Putnam's column. During the course of the battle as it surged to and fro, Putnam found himself in the line of fire - musket balls whistling through the air close to his body. Some thudded into the tree to which he was bound.

The errant musket balls were not his only concern. Behind the enemy's skirmish line Putnam became the centre of attention on a number of occasions. First, a young warrior took time from the battle to test Putnam's nerve or his own accuracy or perhaps both. Repeatedly, the Native threw his tomahawk attempting to get as close to Putnam as possible without actually hitting him. Escaping harm, just barely on a number of throws, Putnam next had to deal with a French officer who attempted to discharge his musket into the prisoner's chest. Fortuitously, the weapon misfired, and deaf to Putnam's pleas for quarter, the Frenchman struck Putnam across his jaw with the stock of his musket.

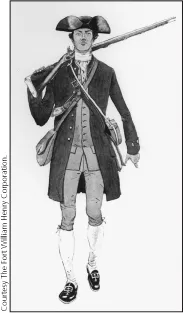

The Natives often proved to be fickle allies.

As the momentum of the battle began to swing in favour of the British, some Natives untied Putnam and dragged him along as they withdrew. A short distance away from the battlefield, the Natives stopped and stripped Putnam of his belongi...