eBook - ePub

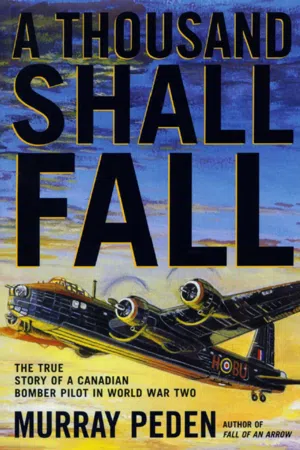

A Thousand Shall Fall

The True Story of a Canadian Bomber Pilot in World War Two

- 490 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the finest war memoirs ever written. During World War II, Canada trained tens of thousands of airmen under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Those selected for Bomber Command operations went on to rain devastation upon the Third Reich in the great air battles over Europe, but their losses were high. German fighters and anti-aircraft guns took a terrifying toll. The chances of surviving a tour of duty as a bomber crew were almost nil. Murray Peden's story of his training in Canada and England, and his crew's operations on Stirlings and Flying Fortresses with 214 Squadron, has been hailed as a classic of war literature. It is a fine blend of the excitement, humour, and tragedy of that eventful era.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Thousand Shall Fall by Murray Peden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

ENLISTMENT – THE RCAF

ENLISTMENT – THE RCAF

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!

To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!

Tennyson: Ulysses

I saw Air Marshal William Avery Bishop only once — at a recruiting rally in the Winnipeg Auditorium in the spring of 1941. I was seventeen, impatiently awaiting my eighteenth birthday so that I could join up. My classmate at Gordon Bell High, Rod Dunphy, sat beside me, both of us exhilarated by the pugnacious speech of the short, stocky flyer who, at that moment, was the greatest fighter pilot alive, with a score of seventy-two confirmed victories.

Eddie Rickenbacker, whose assessment in this field was based on solid credentials, once said that Billy Bishop was a man incapable of fear. Certainly the medal ribbons we could see on Bishop’s chest afforded strong corroboration of Rickenbacker’s assessment: Victoria Cross, Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, to name only the ones we could identify. From the descriptions given by journalists and others I had come expecting to see a gamecock, and in that respect Bishop certainly lived up to his billing. But he was much more than that; he exuded as much dignity as daring, doubling the impact he made on an impressionable audience. Dunphy and I came away convinced that our original intent had been right, and that we should join the Royal Canadian Air Force as pilots as soon as we could qualify, namely, at age eighteen.

My eighteenth birthday fell on a Sunday in 1941, a sore disappointment to me since it prevented me from enlisting until the following day, Monday, October 20th. I was at the recruiting office in the old Lindsay Building when it opened Monday morning. I spent most of that day dressing and undressing in various offices and being subjected by impersonal doctors to highly personal indignities. The air-crew medical was devastatingly thorough.

Just before 6:00 PM I lined up with half a dozen other survivors, this time with my clothes back on, and was sworn in as a member of the RCAF. Our document folders were marked P/O, indicating that we would, if all went well, be trained as Pilots or Observers. (While the individual expressed his own preference, the Air Force made the binding decision, on the basis of performance at Initial Training School, as to whether he would be washed out altogether, or selected for training either as a Pilot or Observer.) I had entered the building in the morning as Mr. D. M. Peden. I left with a slightly swollen appellation: Aircraftsman Second Class (AC 2) PEDEN, DAVID MURRAY, R134578. I was also given an Air Force lapel pin to attest to my heroism, placed on leave without pay, and ordered to report back on November 6th, 1941, for the next draft to No. 3 Manning Depot, Edmonton.

On the appointed day, thirty of us assembled in the CN Railway Station, made our farewells, and, in the late afternoon, headed for Edmonton. After a casual inspection of our coach, I concluded that it had been amongst the rolling stock destroyed by General Sherman when he left Atlanta for his hike across Georgia, had been patched up after the termination of those hostilities and purchased by the Canadian Government for use in situations such as this, where it wished to transport the very cream of its manhood on important missions.

After three hours of drafty progress, I headed with some foreboding for the dining car, clutching a blue Air Force meal ticket in my hand, and assuming that if the meals harmonized with the accommodation I would shortly be struggling with serious gastric disorders. My fears proved groundless; the meal was excellent, and I returned in high fettle to the museum piece in which we were riding. That sensation was gradually eroded as the night wore on. Since our run of about eight hundred miles would be covered in one night, the Air Force policy was to allow its men to begin to develop character by spending the night sprawling in the upright seats of the ancient day coach, seats which I was sure were truncated church pews. It was a long night.

At 6:45 AM, November 7th, 1941, we rolled into Edmonton. The first fine careless rapture had evaporated. The weather in Winnipeg at the time of our departure had been quite pleasant for November, so most of us were lightly dressed. We lurched woodenly out of the coach vestibule and down onto the platform to find the Edmonton temperature some forty degrees colder. We stood for a few minutes with our teeth chattering until an Air Force Corporal gathered everyone together and marched us a short distance to where, with a thoughtfulness which we came in time to recognize as typical, the Air Force had provided two open trucks to speed us to our new abode. On the ride over to the old Exhibition grounds, now the site of No. 3 Manning Depot, with the truck’s speed contributing a 40 mile an hour windchill factor to the frigid air, I realized that the doctors had wanted to be very sure about our physical condition before letting us into the service so that the number of trainees who died of exposure on the way to Manning Depot could be kept within acceptable limits.

These Manning Depots of the RCAF were basically stations where civilians were transformed into uniformed raw material suitable for further training. We were issued dozens of items of standard kit, everything from the various articles of our uniforms down to little “housewives”, or sewing kits for running repairs to uniforms. Despite the age-old serviceman’s complaint that there were only two sizes: too big and too small, the stores clerks attempted, with moderate success, to issue clothes that fitted. However, most of us spent five or ten dollars of our own money and had the finishing touches in the way of final minor alterations done by civilian tailors in town. In short order we began to look like airmen.

As the lowest ranking humans on the station — we were the service equivalent of vermin — we were subjected to further indignities as a matter of routine, and were even preyed upon as fair game by people who were almost as low-caste as ourselves.

The NCO in charge of our platoon, Flight Sergeant Tracy, marched us one morning into the main arena inside the Exhibition Building and left us standing in line, unsupervised, while he disappeared for a few minutes into one of the side offices. A Leading Aircraftsman (LAC) — the Air Force equivalent of the lowly Lance-Corporal — entered the arena and called us to attention in a businesslike tone. He then told us to drop our trousers and shorts around our ankles. “The MO’s giving everyone another short-arm inspection”, he said, “I’ll bring him in now”.

He was referring to the standard test for hernia in males. We had all had such a test upon enlistment, but by now saw nothing unusual in a redundant repetition of any Air Force procedure. We all dropped our slacks, underwear, and dignity, and stood in brutish splendour awaiting the doctor resignedly. The LAC disappeared out another door, undoubtedly choking with laughter as soon as he got out of sight. Flight Sergeant Tracy came back on the scene a few minutes later. His face was an interesting study in suppressed emotion when he beheld his erstwhile immaculate platoon standing about like a gaggle of practising homosexuals. When he could find his voice he asked the obvious questions. We relayed the LAC’s description and instructions, and Tracy sprinted to the door in what proved to be a vain attempt to identify the humorist.

Our first, “noc” parade took place a few days after the foregoing embarrassment. We had some inkling of what to expect, since the sadists who had already been through the ordeal were pleased to leak their horror stories amongst us. We paraded before Flight Sergeant Tracy one afternoon to learn that right now it was our turn for inoculations.

For those who dreaded needles, it was a memorable day. We rolled up our sleeves on both sides and walked between a bevy of white-gowned swabbers, doctors, and catchers. We got five needles in about a minute and a half, and I, who feared and loathed the things, was astonished to find that in our group about one in five simply keeled over and passed out when they got to the big TABT shot, which was third in the stabbing order. Mind you, there was a fearfully big cylinder on that needle. I suppressed a gasp with difficulty and forced myself to look away after I had allowed my gaze to linger on it for a little less than one microsecond; but in that brief appraisal I could see that it was the four cup size. I came through the assembly line quivering but vertical, and as I surveyed those who were horizontal and still showing only the whites of their eyes, my self-respect began to return.

After four weeks of Manning Depot we entrained for No. 7 SFTS (Service Flying Training School) at Macleod, Alberta, for a few weeks of what was officially styled “tarmac duty”, a euphemism for a Joe jobs routine until an opening came up for our flight at an ITS (Initial Training School.) The train trip was uneventful until we got to Red Deer, where the conductor told us we had a 20 minute stop. Three or four of us promptly walked to a cafe about 200 yards away for a cup of coffee. There had been a slight breakdown in communication between the conductor and the engineer, who pulled out smartly and without warning after only ten minutes.

I almost caught up, pelting down the tracks only a few yards behind the train; then it pulled away. I had abandoned hope, although still running furiously, when someone pulled the emergency cord and the train stopped. The conductor was extremely angry, and thereafter no Air Force personnel were allowed out of the coach. I did my best to avoid the glances of my travelling companions.

I spent my first day at Macleod working in the kitchen. Even with its horrible odours and revolting messes it had its advantages, since it was bitterly cold outside, and Macleod was notorious for its continuous 30 mile per hour westerly wind funnelling in from the Crow’s Nest Pass. (The whole time I was on the station, I saw them change the runway only once.) Some of our boys were stuck with guard duty, and even with the excellent parkas they drew, it was an uncomfortable and tedious way to put in the time. I was warm in the kitchen, and was not going to get militant about changing my job until I found something better. Fortunately I did not even have to look. Fate smiled on me the second day, and I gravitated into a sinecure.

Macleod had a station band, and a reasonably good one, under the baton of Corporal Norman Lehman. As soon as a new group of trainees hit the station, Corporal Lehman’s extensively developed system of contacts screened them to find out whether any of them played military band instruments. I let it be known on the first day that I had played solo cornet for the Royal Winnipeg Rifles; and on the second day it turned out that what Macleod needed more than anything else in the world was a band librarian who could keep the music filed and organized, shine up the odd instrument, and play solo cornet.

It was an ideal arrangement. Corporal Lehman had been a barber in civilian life, and was not averse to making an extra few dollars by cutting his friends’ hair at 25 cents a time. In return for my co-operation in helping him tidy up afterwards, and in keeping the whole operation more or less secret — for this moonlighting had to be done very judiciously — Lehman gave me the freest possible rein. Whenever I felt like it, I could go over to the flights and attempt to bum an aeroplane ride in an Anson, as long as there was an instructor along. More importantly, I could go to the Link Trainer instructor, Flying Officer Coghill, a World War I pilot who had flown with the redoubtable Raymond Collishaw, and try to find a free half hour in the Link.

This was extremely important to us potential air-crew, because we knew via the grapevine that when we got to ITS we were going to be tested in many ways to see whether we had the requisite co-ordination and reflexes to become pilots. One series of tests would be given in the Link Trainer, a very sensitive flight simulator; and we all wanted to sit in one and find out what it felt like so that we would not be completely unprepared when we got to ITS.

Strictly speaking, Coghill was not supposed to train us in the Link before we got to ITS, since the purpose of the ITS sessions was to test our aptitude and instinctive reactions, and see how readily we could get used to the hissing instability of the fidgety little trainer. Coghill knew this of course, and would never give any of us very much time in the Link, because too much would destroy the validity of the ITS tests. However, he was a warm-hearted and sympathetic soul, and he knew how desperately keen we were to make good. He reasoned that an hour or so in his Link would give us a little more confidence, take away some of the mystery and apprehension, and still not vitiate the ITS tests in any way. He was a flyer himself; he had the flyer’s kinship with the new fledglings, and we could feel it.

He taught us in a nice way to conduct ourselves appropriately. Once when I carelessly transgressed the bounds of propriety by failing to salute when I entered his office — I was concentrating so much on what arguments I would use to try to get another 15 minutes in the Link that I completely forgot — he lectured me in a very fatherly way about remembering proper military courtesy, and then, with a twinkle in his eyes, said:

“Right. Now climb into the Link, put on the headphones and let’s see what you can remember.”

After 36 years, I think of him fondly still.

Our station band, complete with its accretion of three itinerant and very temporary air-crew members, numbered 27 players. We practised regularly three times a week, and for what was basically a pick-up group, the quality was not at all bad. My initial practice with the group produced a surprise for me that, for the first hour at least, threatened to destroy my usefulness. It came in the form of a burly French-Canadian mechanic with huge hands and knuckles, who would physically have been the best equipped member of the band to tote a big tuba on the march — or to carry an anvil under each arm if necessary. This burly bandsman played the piccolo, and when he got set to play, the tiny pipe would disappear within his huge hands.

Now, piccolo parts are the icing on the military band’s cake, consisting largely of graceful and sweeping chromatic runs, embellishing echo phrases, and frequent, sustained trills. The parts are often demanding; hence our incongruously built musician made his share of errors. Following the more blatant and heinous auditory misdemeanours, Corporal Lehman would rap sharply with his baton in the time-honoured signal to stop and repeat the strain. The memory of the first time it happened in my presence remains etched on my brain.

A bird-like piccolo run, sweeping up and down over several bars to a high trill, was fractured beyond recognition. The bandmaster’s baton rapped sharply against his music stand and the music ceased. In the momentary hush that followed, the piccolo player, his big hands poised ever so delicately before his pursed lips, brought his instrument slowly to his lap, squinted slightly under bushy black brows at the troublesome score, and began to speak. In comments representing the absolute nadir of foul profanity he raked the composer, publisher, distributor, and every other culprit sharing the slightest trace of responsibility for foisting this impossibly difficult passage upon unsuspecting piccolo artistes. What convulsed me was the fact that his extravagant French accent and wildly garbled mispronunciationis somehow transformed the shockingly vulgar condemnations into something resembling an elegant critique.

The rest of the boys, being thoroughly inured to these ambivalent broadsides, merely chuckled, then lifted their instruments promptly at the bandmaster’s signal. I was helpless for five minutes; after I did cork the laughing I lost control two or three times and unleashed triple forte blasts in the most inappropriate places as my thoughts strayed back to Frenchie’s musical insights.

The band was scheduled to broadcast a concert at the radio station in Lethbridge three weeks from that date. One of t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Forewords

- 1 Enlistment - The RCAF

- 2 Initial Training School

- 3 Elementary Flying Training School

- 4 Service Flying Training School

- 5 Convoy

- 6 Bournemouth - Leave - English Map Reading

- 7 No. 20 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit

- 8 Operational Training Unit (First Phase)

- 9 Operational Training Unit (Second Phase)

- 10 Heavy Conversion Unit - Stradishall

- 11 Operational Flying - Apprenticeship

- 12 Main Force Journeymen

- 13 Tempsford - New Secrets

- 14 Farewell to the Stirling

- 15 The Americans Conquer the RAF

- 16 Return to War - With New Weapons

- 17 The Move to Oulton and Blickling Hall – The Invasion

- 18 Gelsenkirchen

- 19 Phantom Fleets and Other Weapons

- 20 Operations - The Secondary Toll

- 21 Closing Glimpses, Mainly Pleasant

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Index