![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE FIRST PENCILS OF LIGHT

They are now employed in letting, at points few and far between—single

pencils, as it were, here and there, of the sun’s rays amongst that boundless

continuity of shade which has hitherto overspread this gigantic land.1

It is difficult for us to imagine what it is must have been like to be among the province’s first pioneers. On his travels through Charlotte County, the Reverend Alexander MacLean observed what he called the single pencils of light that dotted the landscape, as the first few trees were being cleared in the interminable forests. Scottish colonizers would eventually create their communities in these vast wildernesses, but progress in producing cleared farmland was slow. From the time that Britain first secured control over this territory, it was clear that New Brunswick’s destiny would be driven primarily by its wealth in timber rather than its agricultural potential.

France had surrendered Acadia (peninsular Nova Scotia) to the British in 1713. Fearing that Acadians would plot with France and be hostile to her interests, Britain expelled thousands of them from their lands in 1755. Having been removed from their settlements at Minas Basin, Chigecto Bay and the head of the Bay of Fundy, they were forced to relocate to the Atlantic coast between Massachusetts and Georgia. However, several hundred Acadians managed to escape, seeking refuge in the northern wilderness of the future New Brunswick or in He Royale (Cape Breton) and He Saint Jean (Prince Edward Island), which still remained under French control.

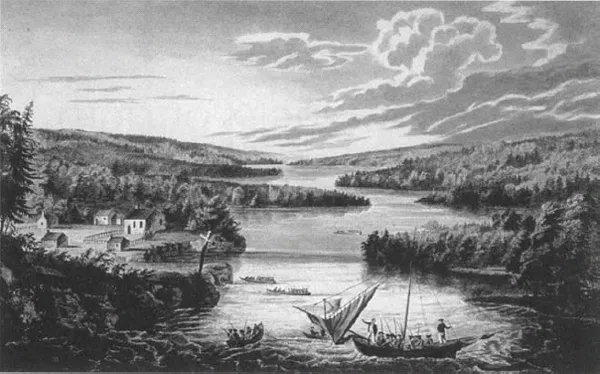

Their principal gathering place was the Miramichi where around 3,500 Acadians were taking refuge under the watchful eye of Charles Deschamps de Boishébert, the Acadian commander, who established his headquarters there. The major Acadian encampment was at the junction of the two branches of the Miramichi River, the aptly-named Beaubears Point (laterWilson’s Point).2 Acadians were also to be found at Beaubears Island, opposite the Point, or at various places along the Miramichi River between present-day Chatham and Newcastle and the coast.3 But this was a temporary respite only since, after the fall of Louisburg in 1758 when British control was extended to present-day New Brunswick and the two islands, they suffered yet another round of deportations. Once again, many escaped detection or fled from the region, returning later to establish Acadian communities along the south shore of the Bay of Fundy, and at Memramcook, Shediac and other places along the eastern coastline of the future New Brunswick.4 The Mi’kmaw, Maliseet and Passamquoddy First Nation people signed their treaties of submission in 1761, and with the removal of most Acadians, Britain’s control over New Brunswick’s land was well and truly secured.5

A view of the Miramichi in 1760 when it was under French control. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Ace. No. R9266-1110 Peter Winkworth Collection of Canadiana.

Four years later saw the arrival of the Morayshire-born William Davidson, founder of the Miramichi region’s lumbering and shipbuilding industries. Being more interested in pursuing his business interests than in promoting settlement, his initial impact on population growth was minimal. A large number of settlers did arrive two decades later when, with Britain’s defeat in the American War of Independence in 1783, nearly 15,000 Loyalists were moved at government expense from the United States to New Brunswick, which became a separate province a year later. Forming the initial core of New Brunswick’s immigrant society, they were mainly located along the St. John River Valley and in the southwest corner of the province at Passamaquoddy Bay. Nevertheless, they failed to attract much in the way of followers, far fewer than had been hoped. On the contrary, many Loyalists were dissatisfied with their new locations and either returned to the United States or found better prospects in Upper Canada. To the dismay of local administrators, New Brunswick soon became a well-trodden gateway to the United States, not just for new arrivals from Britain seeking to avoid American immigration taxes, but also for its own disgruntled settlers. By 1806 New Brunswick’s population was only 35,000, nearly half that of Nova Scotia and Upper Canada and a fraction of Lower Canada’s population, which was almost seven times greater.6

Compared with other parts of the eastern Maritimes, New Brunswick was a late developer. Various settlement promoters recruited large numbers of Highlanders in the 1770s to colonize areas of Prince Edward Island and Pictou, Nova Scotia, but the future New Brunswick, which did not then exist as a separate colony, was totally bypassed.7 Its sudden intake of Loyalists a decade later gave it mainly American-born settlers, who retained fairly distant ties with the disparate parts of Britain from which their families had originated. In stark contrast to them were the Highlanders and Islanders who first colonized Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. They came in large, organized groups and quickly created successful communities, which in turn became powerful magnets for follow-on emigration from those areas that had fostered the original settlement footholds. The tide of immigration had still not reached New Brunswick by the end of the 18th century, a time when Scottish colonization was overflowing into Cape Breton. This was the case even though Scottish ships were sailing from the Clyde to the New Brunswick ports of Saint John and St. Andrews to collect timber, thus providing transport to would-be emigrants.8 It took the severe economic depression, which followed the ending of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, to kick-start immigration to New Brunswick. The province then experienced a large influx of people during the first half of the 19th century from all parts of Britain, although Irish immigrants greatly outnumbered all other ethnic groups.9

In spite of having reasonable quantities of good fertile land, agricultural development was slow and fraught with difficulties. The province oscillated between offering free land grants or insisting on land sales, as it searched for the best compromise between attracting colonizers, discouraging speculators and keeping sweet the various mercantile interests and the elite families who essentially governed the province. While settlers normally had to overcome huge bureaucratic obstacles to acquire land, a speculator like Edward Kendall, from Greenock, who had purchased land at Aroostook (Victoria County) purely as an investment to sell on to a lumber company, could make his fat profit without setting foot in the province.10 Such men put large tracts of land beyond the reach of ordinary settlers, causing resentment and serious impediments to the progress of colonization.11 Settlements eventually materialized from a chaotic mishmash of part-land grants and part-land sales and from settlers circumventing the law by seizing possession of their lands through squatting.12

The province’s long winters seemed also to militate against its agricultural development. During his 1827 tour of British North America, Lieutenant-Colonel Cockburn, who advised the government on colonization matters, noted that in New Brunswick “the greatest inconvenience arising from the length of the winters is the quantity of fodder” required for farm animals, while damage caused to crops by early frosts was also a serious problem.13 And yet, when Alexander Munro visited the province thirty years later, he was much more optimistic, claiming that the province’s climate was “very healthy” and that the high snowfalls, “sometimes as much as five feet,” contributed to the fertility of the soil.14

Although most Highlanders and Islanders could cope well with a cold climate, the endless, dreary forests were much harder to bear. Because they were used to living by the sea, the miles of splendid coastline offered by Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton and peninsular Nova Scotia gave them a semblance of a home from home. By the same token, New Brunswick’s massive forests and land-locked position were far less appealing. Its forests were said to be so dense that even before beginning the task of chopping down trees to create farms, settlers had first to “cut their way in.”15 Little wonder then that New Brunswick was their least favoured choice.

Yet, however gloomy they appeared to the first wave of settlers, the forests were the province’s main resource. The large increase in tariffs on Baltic timber, first introduced by Britain during the Napoleonic Wars, gave North American timber a considerable cost advantage over traditional supplies from the Baltic.16 The trade mushroomed and by 1816 wood products accounted for 90 per cent of the province’s exports to Scotland.17 The growth in trade caused the volume of shipping between Scotland and the province to soar, bringing affordable and regular transport to emigrants. As trading links developed, emigrants could simply purchase places in one of the many timber ships that regularly crossed the Atlantic.

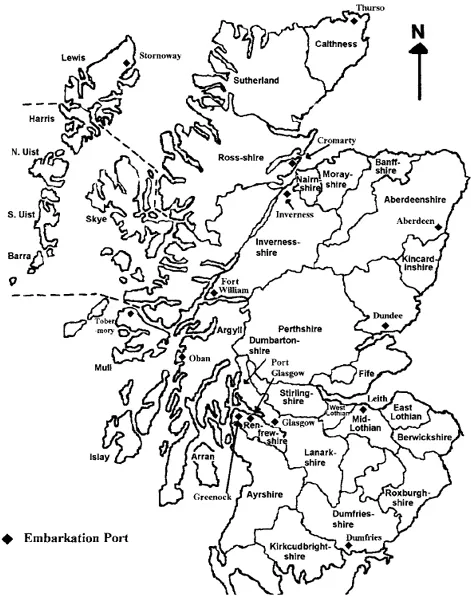

Figure 1: Reference Map of Scotland

The timber trade was the driving force of New Brunswick’s economy. Even though the industry was regularly plunged into boom and bust conditions, according to the fluctuations of business cycles in Britain, it offered diverse employment opportunities and was a vital component of a settler’s livelihood. As Peter Fisher noted in his History of New Brunswick, published in 1825, “the woods furnish a sort of simple manufactory for the inhabitants, from which, after attending to their farms in the summer, they can draw returns during the winter for those supplies that are necessary for the comfort of their families.”18 For the very poor, it provided the means to earn money to purchase land, although in New Brunswick, there were plenty of lumbermen who never became farmers.

Agricultural development was overshadowed by the timber trade in many parts of New Brunswick, and for people who longed to see neat, cultivated fields, it was an abomination. Joseph Bouchette found the thickly forested areas of Northumberland, Kent and Gloucester counties to be “the thinnest settled and the worst cultivated in the whole province. There is scarcely any collection of houses worthy of the name of a town in any of them.”19 There was a wealth of wood but only marginal amounts of farmland and so settlements had spread like long, slender fingers along the coastline and riverbanks.

Scottish Loyalists had dominated the lumbering industries that were established in Charlotte County from as early as 1784; yet they inspired few fellow Scots to join them. However, as the focus of the timber trade moved slowly northward, it began to draw emigrant Scots first to Northumberland and Kent counties and later to Restigouche County. The Scottish influx mirrored the progression of the trade, building on the first footholds that had been established by William Davidson’s recruits along the Miramichi River in the late 18th century. When the forests of the Restigouche were cleared in the mid-1820s, the pattern was repeated and once again Scots dominated the early influx. The trade’s principal financiers and merchants were Scottish, and in the forefront were Allan Gilmour and Alexander Rankin, both of whom became the great timber barons of their day.

Thus, the remarkably strong links that developed between Scotland and the northern areas of the province owe much to William Davidson’s entrepreneurial talents, but another key factor was the Loyalist influx that began in the late 1780s. A good many men of the disbanded Royal Highland Regiment (42nd), who had settled with their families along the Nashwaak River north of Fredericton, left their allocated holdings and moved northward to join Davidson’s recruits in the Miramichi. They brought military discipline and organizational expertise with them and according to Patrick Campbell, a passing visitor, it seems they also came with considerable practical skills:

Here, I was told that the Highlanders settled up the river were in many respects not a whit better than real Indians, that they would set out in the dead of winter with their guns and dogs, travel into the deepest recesses of distant forests; continue there two or three weeks at a time, sleeping at night in the snow and in the open air; and return with sleds loaded with venison, yet withal were acknowledged to be the most prudent and industrious farmers in all the province of New Brunswick and lived most easily and independent.20

The Highland Loyalists undoubtedly prospered and attracted...